The literature on effective teacher professional development (TPD) declares that teachers’ learning is facilitated and sustained in communities that are collaborative endeavors, that acknowledge and value participants with different levels of expertise, and that focus on practice-related issues (Guskey, 2003; Hargreaves, 2003; Huberman, 1992; Lieberman, 1995; Loucks-Horsley et al., 1987; Loucks-Horsley, Hewson, Love, & Stiles, 1998). Such results justify the potential benefits of including an online dimension for TPD endeavors (Harasim, Hiltz, Teles, & Turoff, 1997; Muscella & DiMauro, 1995). Yet previous research reveals that initiation and maintenance of such online communities are challenging (Schlager & Fusco, 2004). This paper investigates the viability of developing a Web-supported dimension to the Literacy Project, a successful face-to-face professional development community of teachers in a western Canadian city.

Purpose of the Study

Established in 1999 as a school-based initiative, the Literacy Project was designed and implemented by teachers from public schools and now includes 70 schools and over 700 teachers. To support new participants with their professional development needs, the Project has secured up to 5 years of district-level support through district-appointed mentors and designated school-based coordinators, all of whom have part-time release from classrooms. The project has also developed collaborative ties with a local university. Findings from an earlier study revealed that the Literacy Project’s teachers had developed a sense of belonging to a professional learning community and that they desired continuous access to the effective professional development they received as part of the Project (Clarke, Storlund, Wells, & Wong, 2004).

With the growing number of schools wishing to join the Literacy Project, the teachers’ desire to communicate with their colleagues across schools, and the limited pool of mentors and coordinators as main sources of support, the idea of adding an online component to this project was compelling. In this paper, the online component is referred to as the On-line Literacy Project (OLP).

Informed by the theoretical perspectives of communities of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Wenger, 1998) and TPD (Guskey, 2003; Hargreaves, 2003), this research explored the nature of online interactions among a group of the Literacy Project mentors and coordinators and investigates the factors impacting their participation in OLP.

Review of Literature

Theories of social constructivism recognize learning as an integral part of practice and emphasize learners’ active role in constructing knowledge by collaborating with peers (Barab & Duffy, 2000; Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989; Lave, 1997; Lave & Wenger, 1991;). Communities of practice are emergent, tightly knit groups that share mutually defined practices and sets of beliefs and a common history developed around a shared enterprise (Lave & Wenger, 1991). Considering the new perspectives in TPD, investigating how teachers benefit from professional learning communities may lead to new opportunities for TPD.

Effective Teacher Professional Development

Recent approaches to TPD favor collaborative activities that draw on teachers’ previous knowledge and expertise (Loucks-Horsley et al., 1998). Guidelines for effective TPD emerging from the literature include attending to teachers’ needs at various stages of their careers; smoothly infusing innovative practices that are responsive to teachers’ immediate concerns; involving teachers in the planning and implementation of TPD programs; and building on teachers’ existing experience and knowledge (Guskey, 2003; Loucks-Horsely et al., 1987; Loucks-Horsley et al., 1998, Hargreaves, 2003; Huberman, 1992; Lieberman, 1995).

Extended collaboration among teachers could enable effective TPD by mitigating teachers’ diffidence and sense of incompetence in the face of innovations, legitimizing their expertise at all experience levels, and facilitating access to existing expertise in the form of mentoring and coaching (Guskey, 2003; Hargreaves, 2003; Loucks-Horsley et al., 1987; Loucks-Horsley et al., 1998). As well, Hargreaves (2003) promoted professional learning communities in which teachers’ knowledge and practice improve through deliberative inquiry. Communities of Practice, then, appear to be a suitable conceptual framework for studying collaborative TPD.

Web-Supported TPD Communities

Web-supported professional communities have become increasingly popular as parts of TPD programs or as a means of TPD (Schlager & Fusco, 2004; Zhao & Rop, 2001). Perceived benefits of Web-supported TPD, as reflected in Zhao and Rop’s (2001) review of 14 in-service programs and in Barnett’s (2002) examination of 24 pre- and in-service programs, include reducing teacher isolation and facilitating information exchange and experience sharing; promoting new practice and supporting teachers in implementation processes; developing a community of teachers around practice; and facilitating a reflective discourse about teaching. Despite potential promises, sustaining these communities has proven challenging.

Existing studies on Web-supported TPD communities, especially research conducted on Tapped In, the Inquiry Learning Forum, and the New Teacher Support E-Mentoring Project, reveal a series of recurring issues with regard to community initiation and sustenance. Tapped In (www.tappedin.org), Inquiry Learning Forum (http://ilf.crlt.indiana.edu), and New Teacher Support E-Mentoring Project (http://ntsp.ed.uiuc.edu) differ in scope and implementation, but are all developed in research institutes and universities by multidisciplinary teams consisting of academics, technologists, and K-12 teachers. Other studies relevant to Web-supported TPD communities were also considered in the review of literature. The resulting trends are as follows.

Increasing ownership. An online TPD community increases teachers’ access to an extensive collection of resources and provides opportunities for teachers to pursue new roles. The extent to which teachers use such opportunities, however, is not fully determined.

A pilot study conducted on a Tapped In-hosted online component of a districtwide support initiative to improve new teachers’ retention rate showed that teachers tend to fall back on face-to-face practices in online settings (Schlager, Fusco, Koch, Crawford, & Phillips, 2003). The researchers noted that, still loyal to the “one expert to one group of teachers” model, the facilitators (in this case each assigned to one group of teachers) disregarded the opportunity for communication across groups.

Teachers’ reluctance to break out of their traditional role is also reported in Klecka, Clift, and Thomas’s (2002) action research that investigated how the New Teacher Support E-Mentoring Project facilitated communications between 41 new teachers and their e-mentors. Initial findings disclosed that e-mentors perceived their role as “answering the questions asked by e-mentees,” which made them reluctant to initiate discussions or ask questions. Drawing on the research on the Inquiry Learning Forum, Kling and Courtright (2004) argued that teachers may require training and scaffolding to become more proactive community members.

Computer mediated communication tools can facilitate communications among new members and old timers of a Web-supported TPD community (Schlager & Fusco, 2004). Yet, the communication happens only in the presence of a distributed leadership, in which all members, regardless of their rank, can fully contribute to the community. On the other hand, equal access may affect the quality of contributions. For example, Barab, MaKinster, and Scheckler (2004) reported that the teacher advisory board (teachers who collaborated with the Inquiry Learning Forum research and design team) was concerned about the quality of classroom videos shared online and, thus, had to develop a review protocol for submitted videos.

Quality of online discussions. Teachers are expected to discuss their practice more often in Web-supported communities rather than face to face. But the evidence for teachers having critical discussions in Web-supported communities is contradictory. A study of 14 teams of teachers who participated in two TPD programs using Tapped In’s text-based synchronous meeting, showed when project leaders and teachers acquired online discussion skills they could lead professionally focused discussions (Schlager, Fusco, & Schank, 2002).

Barab, MaKinster, Moore, and Cunningham’s (2001) study of three Inquiry Learning Forum teachers, however, bears different results. Participants were a teacher who shared classroom videos (contributor member), a teacher from a special interest group, and a preservice teacher. The contributor member complained about disconnected online discussions and lack of critical feedback. Although he trusted the potential of Web-supported communities of practice for TPD, his expectations from New Teacher Support E-Mentoring Project had not been met. The teacher from the special interest group, too, was frustrated by the limited number of teachers who joined the discussions and the low quantity of communication. As for the preservice teacher, online discussions were part of her course work requirements, but she found them only partially useful.

In another study, 3,500 discussion forum messages posted by 900 special needs educators were analyzed to examine how the discussion forum was used and if the educators were successful in the formation of an online community. Messages were categorized as exchanging information, seeking support, and sharing exhaustions. Again, critical discussions were rare and limited (Selwyn, 2000). These findings are verified by Kling and Courtright (2004), whose overview of Inquiry Learning Forum members’ activities from 2001 to 2002 revealed that messages in different parts of the forum contained little critical discussion and, instead, teachers asked for clarification and reflected their opinions about topics of discussion without connecting their contributions to the collective interests of the group.

Anonymity. Teachers’ reluctance to critique their peers is probably intensified in online settings due to partial anonymity. Barab et al. (2004) contended that teachers are reluctant to criticize ideas when they barely know the owner of the idea. However, the effect of anonymity on online discussions varies with context. For example, new teachers felt safer to share questions and problems anonymously (Klecka, 2003).

Effect of participation on teachers’ practice. Teachers’ content knowledge and pedagogical knowledge increased as they spent more time in Tapped In (Fusco, Gehlbach, & Schlager, 2000). Two Inquiry Learning Forum teachers and one preservice student noted that participation in the forum had insignificant effect on their practice (Barab et al., 2001). Explaining the design considerations of a Web-based inquiry science environment, Cuthbert, Clark, and Linn (2002) emphasized that online communication and resultant professional development can be sustained only if they support teachers’ practice.

Usability of technological infrastructure. Web-supported communities rely on Computer Mediated Communication tools as a means of communication among members, but complex user interfaces may deter participation. Sometimes what seems an intuitive interface for designers is too complicated for teachers. The teacher advisory board of the Inquiry Learning Forum was concerned about the complexity of the interface, which was based on a building metaphor (Barab et al., 2001). Likewise, Fusco, Gehlbach, and Schlager (2000) reported that having to learn various commands in the Tapped In environment impeded users’ participation. They suggest that a simplified version would suit new users better.

High school teachers and community college teachers involved in an Earth and space science TPD program used Tapped In communication tools for professional discussions. Their comfort level with using Tapped In resources gradually increased as they spent more time in the environment (Schlager et al., 2002). The effect of training the teachers received before the program was not accounted for. Engaging teachers in the technological design phase was imperative for Web-supported TPD communities (Barab et al., 2004; Schlager & Fusco, 2004).

Promoting participation in Web-supported TPD communities. Involving credible experienced teachers and providing external incentives in the beginning phases of community development has been recommended (Klecka, Clift, & Cheng, 2005; Reynolds Treahy, Chao, & Barab, 2001). Nevertheless, to sustain a community teachers need high internal motivation (Klecka et al., 2005). Teachers’ motivation to participate in Web-supported communities may increase if the activities are related to their face-to-face community (Barab et al., 2004; Kling & Courtright, 2004). Klecka et al. (2002) observed positive effects of relating online discussions to face-to-face teachers’ meetings; face-to-face meetings could set the stage for online discussions. Similarly, Schlager et al., (2003) and Schlager and Fusco (2004) suggested that Tapped In should be integrated in systemic TPD programs. A Web-supported TPD community’s chances for survival and growth may increase if it is developed based on the needs of an existing face-to-face community.

Identifying the Gaps in Previous Studies

Lack of qualitative measures for teachers’ participation in Web-supported communities is a significant gap in the current literature. Previous studies rarely provide in-depth accounts of whether the participants recognized themselves as community members and whether the community positively affected their professional development.

Partnership between academics and K-12 education systems in initiating Web-supported components for new or existing teacher communities is another rarely studied phenomenon. When the idea of adding an online component to TPD programs comes from outside, teachers tend to perceive it with decreased feelings of ownership, which might impede their participation.

Determining how a Web-supported community could respond to teachers’ needs is also important. Havelock (2004) warned against neglecting the effect of teachers’ face-to-face communities when attempting to develop Web-supported TPD communities. More research is needed to find out how perceived needs for online technologies would affect teachers’ participation in the activities of Web-supported communities.

Technological design of Web-supported communities also requires further investigation, as well as how usability affects the level of participation.

Both researchers and participating teachers are concerned about the quality of online communications. However, more research is needed on the methods by which teachers start online interactions and the substance of these interactions.

This study, therefore, seeks to answer the following questions:

- What are the participants’ perceptions of the potential of the OLP, a Web-supported professional community, as an extension to their face-to-face community?

- What factors would affect their participation in OLP?

- How did the participants make use of the discussion forum?

Methodology

An interpretive case-study design (Merriam, 1998; Stake, 1995) that allowed for thick description, explanation, and interpretations of the processes involved in the development and growth of OLP was adopted to conduct the study.

Study Site

The Literacy Project did not have an online component prior to this study. With the help of a Literacy Project mentor, the research team developed a public resource Web site and selected an open-source, password-protected discussion forum for online communications. Later, other mentors provided feedback on the Web site, and the site was revised based on their reflections. Both Web components were hosted on a local university server.

Participants

The Literacy Project has set up two levels of peer support: mentors and coordinators. Mentors work at the district level and are responsible for all of the schools affiliated with the project, while coordinators serve the school in which they teach. School coordinators can contact any of the mentors at the district level to consult about the problems they face and the professional support they need. Early in this study, the research team decided to invite mentors and coordinators to participate in the study because they had frequent project-related communications.

An initial call for participation was made in September 2005 in a district meeting where the Literacy Project mentors browsed the newly developed OLP Web site and received hands-on training with the discussion forum. Meetings with school coordinators took place in late November 2005 due to a province-wide industrial strike.

Six participants, including four mentors and two school coordinators, volunteered to take part in the study. Criteria for participation included Internet access at home, ability to work with word processing software, and use of email on a daily basis. Participants were expected to contribute to the discussion forum at least once a week to share their questions and concerns with regard to the Literacy Project or provide feedback to the posted questions. In the remaider of this paper participating mentors and coordinators will be addressed as “participants” unless their role significantly affected their responses. Table 1 summarizes information pertinent to participants.

Table 1

Summary of the Participants’ Professional Information

| Pseudonym | Years of Teaching Experience | Years in the Literacy Project | Responsibility in the Literacy Project* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chica | 9 | 6 | Mentor |

| Jen | 6 | Less than 1 year | Coordinator |

| Pam | 6 | 2 | Coordinator |

| Rachel | 27 | 7 | Mentor |

| Theresa | 22 | 6 | Mentor |

| Wendy | 12 | 6 | Mentor |

Data Sources

Three sources of data were used for this study: participant interviews, contents of the online discussions, and the principal researcher’s research journal.

To gain an in-depth understanding of how the participants perceived of and engaged in OLP, face-to-face semistructured interviews were conducted both at the beginning, September to November 2005, and the end of the study, April to May 2006. Due to an unexpected teacher strike the first round of the interviews took longer to complete than was originally planned.

The first interview focused on the participants’ teaching background, experience with the Literacy Project, interpretation of how it had effected their teaching and students’ learning, their attitude toward technology and its use in teaching and professional development, motivation to volunteer for the research study, expectations of OLP, and predictions of how they would use OLP in the coming months. Informed by the participants’ actual use of the OLP, the second interview probed into the users’ experience with OLP and their interpretation of a professional community. Only those participants who had contributed to the discussion forum were interviewed for the second time.

Examining contents of the discussion forum served two major purposes: (a) revealing the nature of discussions and participation patterns and (b) providing evidence to assess whether the participants succeeded to develop an online community.

As a progressive record of the study, the principal researcher’s journal provided detailed information about the research process, the researcher’s perception of the participants’ engagement in the OLP, and the researchers’ own account of the evolution of OLP. All email correspondence with the research group was entered in the journal.

Analysis

An inductive constant comparative method (Merriam, 1998; Marshall & Rossman, 1999) was used to identify emergent categories, place data into categories, and look across the categories for insights into research questions. Interviews were analyzed in two phases: a preliminary analysis after the first round of interviews and a comprehensive analysis including both first and second round interviews. Messages posted to the discussion forum were reviewed to establish commonalities and differences of themes, nature of responses, and patterns of participation. Entries in the researcher’s journal were used to situate interview and discussion forum data within the contextual conditions of the study (e.g., the industrial job action).

Limitations of the Study

This case study focused on a particular project—the Literacy Project—and a small group of participants. Findings of this study are more specific to this case, and generalizing them to other contexts should be done with caution. Nevertheless, other communities of teachers with similar structures to the Literacy Project may learn from this study.

Another limitation was the unexpected 3-week job action in the beginning of the study resulting in a delayed introductory meeting with coordinators. The volunteer coordinators started their participation toward the end of January 2006. The nature of their participation and, as a result, the findings of this study, might have been different had they started at the same time as the mentors.

The discussion forum software, which was the best choice considering the scope of the study, did not provide detailed information on the exact date and time of the participants’ login into the forum, the amount of time they spent there, and which discussion topics they read.

Findings

Findings of this study are organized in response to research questions, covering the clusters of themes that describe the participants’ perceptions of the OLP, the factors that affected their participation, and their contributions to the discussion forum. Actual excerpts of interviews and discussions in the OLP discussion forum have been included for illustrative purposes. The interview excerpts, where included, are representative of a pool of interview data from the participants that fell into those particular categories of response.

Perceived Significance of the OLP Initiative

OLP originated from a joint research project between the local university and the school board and relied on the premise that the Literacy Project had outgrown its capacity for supporting the current mentoring load. However, interview data revealed conflicting evidence regarding a shared perceived need for an online or Web-supported component.

Common need for OLP. When the OLP prototype was first introduced to mentors, they were excited about having an online dimension to the project. To clarify the practical value of OLP, research participants were asked to identify the perceived need OLP might meet. A major need had to do with mentors’ time and capacity constraints, and a second, less significant need was enhancing the Literacy Project.

Participating mentors believed that online technologies could facilitate their communication with each other and with teachers from other schools, alleviating some of the heavy workload that currently prevented them from having more face-to-face communication. The implication was that OLP could strengthen the Literacy Project community.

With the online forum I see it as a way to get a discussion going when you are not in the same room with somebody…in schools it happens in staffroom … for us as mentors we are so busy even during our mentoring days that we hardly get those times to sit and talk. I think the forum provides us with a way of dialoging with each other… when you don’t often get the chance to see all those colleagues. (Interview 1, Wendy, November 7, 2005)

Despite the OLP’s potential to extend communications among mentors and coordinators, the participants did not think of OLP as a vital need to the project. There was no doubt that OLP would be beneficial, but the participants believed that even without it the Literacy Project would not be paralyzed, because they could still use other available resources, such as email, to make the contact as needed.

According to a participant, surveying a larger group of Literacy Project members would further clarify the need for OLP. However, whether all participants shared an understanding of what OLP could offer was difficult to determine, as a participant argued: “I don’t even think the mentors truly understood how to use this as a form of communication in supporting teachers” (Interview 2, Theresa, May 2, 2006).

Doubts about the future of OLP. The second interview probed the participants’ perceptions of the success or failure of the OLP initiative. One participant who was interested in and passionate about the initiative from the beginning hoped that OLP would continue. She believed that people were using it and had found it valuable. Yet, such devotion to the initiative was rarely observed in other participants, thereby challenging her assessment. Another participant offered a more realistic stance to the success of OLP, arguing that the initiative has started people thinking about the possibilities.

Theresa, the mentor who had close ties with the research team, did not see a huge impact of OLP on the Literacy Project. Comparing the initiative to her personal experience of how it takes time for some ideas to prove useful, she believed that it was still early for the initiative and that people would understand it better much later in its evolution.

It has been eye opening for me and where people are with respect to using the technology. …I don’t know if we were even ready, for having this way of talking to people and with one another….We might have been ahead of our time. (Interview 2, Theresa, May 2, 2006)

Another concern regarding the OLP initiative was its continuity. An uncertainty existed about who would take on the initiative after the pilot study was over and whether the district would be interested in supporting it. The participants were skeptical of the district being supportive or even interested. Based on one mentor’s prior experience, technology was a low priority for the district, as evidenced by the lack of a necessary infrastructure for an online component. This deficiency had in the past prevented teachers from even thinking about such possibilities. The following comment represents the participants’ concerns:

I’m worried about what is going to happen next year….I would love to have it here by (the school board) and that may happen but I don’t know.…Perhaps we can have someone like [an employee] helping to manage it…because there needs to be someone with enough technological savvy. (Interview 2, Rachel, April 20, 2006)

Factors Impacting Participation in OLP

A number of interrelated factors impacted the development of OLP:

Time constraints. All of the participants cited lack of time, especially after school, for their limited contribution. It was interesting that they had decided to use their time at home and not at work to contribute to OLP. For the two coordinators who were full-time teachers and had limited access to a computer during the day, contributing from home made sense. However, mentors expressed that their time at the district office was so full with mentoring or organizational responsibilities that they could not count on it for contributing to OLP: “Any teacher has [problems finding time] and to actually have the mental capacity left at the end of the day to actually think straight. This job is exhausting.” (Interview 2, Jen, April 20, 2006)

Relevance to practice. The participants mentioned that OLP had not been a priority for them. When asked what could encourage her to contribute to OLP, Wendy’s response captured the essence other participants’ perspectives: “I think the main thing is if they go to a Web site or discussion forum [those spaces have] to have something that is relevant and practical” (Interview 2, April 25, 2006).

Pointing to the mismatch between what was presented on the OLP Web site and her interests, a French immersion mentor said that she would be interested in participating in OLP if it had a French immersion component. Recognizing limited available resources for French immersion, she thought the OLP could be valuable for this group of teachers.

“Relevance to who” was also important (Informal conversation with a participant, January, 2005). Some suggestions were made that new teachers would benefit more from OLP because they would have more access to technology and are more competent in using it.

Considering teachers’ concerns with whether the OLP innovation added value to what they already did, relevant content could encourage them to contribute to the Web site and participate in the discussion forum.

Access to credible answers. The discussion forum could be a valuable repository of questions and answers to which teachers refer. Facilitating access to people who can provide credible answers could positively affect participation in the OLP discussion forum: ” I think if you were able to ask a particular question, I think I got an answer from an expert that I see as a valuable tool. So there would be an expert giving me an answer not for me to discuss per se” (interview 1, Chica, November 10, 2006).

Judging the credibility of answers appeared to be a minor concern, as one coordinator mentioned that they had enough professional expertise to verify the answers. Having said that, anonymity or lack of knowledge about a respondent could have also impacted the participants’ trust in the answers they received. Participants used their real names and were familiar with each other’s expertise. Although receiving answers to literacy related questions might increase the use of the discussion forum, teachers were not deterred by the possibility that the answer they received might be misleading.

Active discussions. Discussions in the discussion forum had a rocky start due to the unexpected industrial strike, and after a time low participation levels in the discussions discouraged active participants from further contributing. Whether active discussions would be sustained in the discussion forum was a concern for the coordinator who, based on previous experience with a discussion forum in a graduate program, believed that teachers would not invest time in this form of communication. On the other hand, one mentor who had considerable hope for OLP expressed her dissatisfaction with the silence in the discussion forum and suggested that it might take a long time before teachers adopt online communication tools as a means for professional communication.

Commitment to participation in OLP. Closely related to the activity level in OLP was the gradual decrease in the participants’ commitment. In the beginning, they were careful to fulfill participation requirements, that is, posting in the discussion forum once a week. The commitment levels decreased with time, and participation in the online discussions lost significance. As one participant reflected, “I don’t even feel like we experimented with it. I think it was one more thing for people to do, and I don’t think that any of us really got ourselves to a place where it is like, ‘yes, this is a great thing to do’” (Interview 2, Theresa, May 2, 2006).

Another recurrent theme was that as a group effort, the OLP could not survive with only one or two people using it. At times the participants stopped posting messages in the discussion forum to avoid being the only one talking: “The other thing that held me back was that it is me talking all the time. Maybe I should let someone else have a say” (Interview 1, Wendy, November 7, 2005).

Sociotechnical issues. In preparation for developing a sandbox version for the OLP, the research team consulted the Literacy Project’s consultants and mentors. As a result, the contents of the Web site reflected Literacy Project teachers’ expectations. Discussion forum format was selected by the researchers. Several insights pertaining to the social implications of the choice of technology surfaced during the interviews highlighting how perceived and experienced technological benefits and problems affected participation in OLP.

Perceived benefits of discussion forums, such as providing support and reassurance and having a safe place to leave questions so that others could answer them at a convenient time, could promote its use among the Literacy Project’s teachers. The possibility that the discussion forum would offer low status or shy teachers a chance to express their opinions in a safe environment was mentioned by one participant.

Often time when you are sitting face to face with someone who is strongly disagreeing with you, you’d be reading their eyes…and it might be uncomfortable to speak back. But when you are doing it online, you are not reading any of that. You cut all that and you’re just looking at the words and that’s a good thing…. There is no bullying. There is no intimidation. (Interview 1, Rachel, November 10, 2006)

The resource Web site developed for this study was maintained by the principal researcher. This strategy worked for a small-scale study, but the participants believed the Web site would reflect teachers needs more effectively if teachers could directly contribute to its content. For example, one mentor suggested using automatic submission forms for uploading lesson plans.

Learning to use the discussion forum involved a steep learning curve. Although these teachers were fluent email users, some had problems when working with the discussion forum. One participant, for example, forgot the instructions and confused the email form on the Web site with the discussion forum. She described her actual experience:

I think I put something in the discussion on the Web and Theresa emailed me back. Still haven’t got that figured out yet…. Look I’m a little bit confused.…when I posted that question was that on the discussion forum?… So that’s what I don’t get. Cause I’ve never posted messages before or stuff like that. So that’s why I … I kinda don’t know what I’m doing. That’s what I’m asking. Because I thought maybe I posted it on message board but actually I have posted it on the Web site. I wasn’t sure what I was doing. (Interview 1, Pam, February 4, 2006)

One mentor felt insecure using the discussion forum due to feeling uneasy about sharing ideas or asking questions in a place visible to every member of the Literacy Project: “I’m not comfortable with discussion forums. I think if I want to speak to somebody, I’d much rather talk to them personally. I don’t like the idea of writing to computer or use the computer to discuss ideas” (Interview 1, Chica, November 10, 2005). This was, nevertheless, a personal issue, and it was hard to think of other strategies than one-on-one coaching that might attract her to the discussion forum.

Using OLP purposefully. In this study, the participants were not required to use the resource Web site or the discussion forum to accomplish specific tasks. The approach was to give them a blank canvas and see what they might do with it. In their interviews, however, the participants expressed that well-defined goal-oriented tasks would encourage them to use OLP more frequently. They also suggested some activities, which ranged from replacing some of the face-to-face meetings, like mentors meetings, with online meetings to keep in touch with coordinators or teachers when face-to-face meetings were not feasible.

Learning possibilities. OLP’s TPD potentials were expected to affect the participants’ interest in it. This expectation proved right when the participants talked about their experiences in the discussion forum. They recognized different learning opportunities in the discussion forum, such as when two or more people are carrying on a discussion, when they start a discussion and try to put their ideas into writing, or when others read discussions without responding to them: “What I think it is beneficial for is that everyone gets access to that conversation that’s going between two people. Although they may never participate, they may take a glimpse into the thinking” (Interview 1, Wendy, November 7, 2005).

However, limited reciprocity annoyed the participants, making them doubt if anyone had used or even read their ideas. Despite the unanimous agreement that the discussion forum could be a learning venue, the participants were unsure about the depth of learning and whether or not the discussions grew beyond asking questions about daily practices. Both mentors and coordinators expressed their wished for more in-depth conversations in the discussion forum, for example,

In terms of real thoughtful or thought provoking dialogue, I don’t know if that’s going to be the place…it is interesting to chew over ideas. But probably it would be about more practical things like Theresa said, “How do I get my kids to talk?” I said, “How do I learn to talk less.” They are all just practical things. (Interview 1, Jen, February 6, 2006)

Effect of job action. The Provincial Teachers Federations’ industrial job action from October 7-23, 2005, severely affected this study. The participants signed the consent forms on September 13, 2005, and were immediately distracted by the strike-related issues. From that time onward, participation in the OLP became less of a priority. In the same way, all the scheduled meetings for the Literacy Project were postponed due to the strike, and the meeting with coordinators planned on the first of October 2005 did not take place until November 22, 2005.

Participants Use of OLP Discussion Forum

The p articipants were required to contribute to the discussion forum on a weekly basis by posting messages or providing feedback to posted messages. During the study, the participants initiated 18 discussion topics, 15 of which were considered in this analysis, because the other three were posted by people who opted out of the study. Overall, 37 messages were posted to the discussion forum.

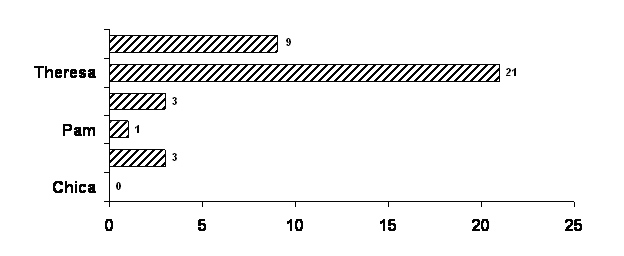

The number of messages posted to the discussion forum varied among the participants, depending on their commitment to the OLP, interest in using the discussion forum, perceived benefits of the discussion forum to provide learning opportunities, and available time. As Figure 1 shows, Theresa, who had close affiliation with the research team, and Wendy, who was highly self-motivated and interested in learning with the discussion forum, posted the majority of the messages. Messages sent to the discussion forum fell into three categories: sharing personal practice and experience, asking more questions to solicit responses, and argumentation.

Figure 1. Portion of each participant’s contribution to the discussion forum.

Figure 1. Portion of each participant’s contribution to the discussion forum.

Sharing personal practice/experience. In response to most inquiries, mentors and coordinators shared their own experience without imposing their ideas on others. They shared the strategies they used to address a specific issue and then usually asked for feedback. The case was different for a coordinator who asked a “how to” question and who also provided the only indication of the practicality of the response she received. Following is part of a conversation between a coordinator and mentor, in which each of them talked about their own experience with an issue:

Jen: I loved what [a speaker] had to say yesterday. So I told the class this morning, “I learned something yesterday, that teachers talk in sentences that are too long. Have you noticed?” A resounding “YES!”… So, all day I tried very hard not to say so much.… Has anyone else tried using less air space? Any suggestions?

Theresa: …so the next day while teaching a Gr.1 class I just created the conditions for the kids to talk…in my own class I have a rule based on their ages…If I teach 5 yr. olds … I can talk for only 4 minutes then its their turn … 6 yr olds … I have 5 mins. to teach … we include using the clock and my students hold me accountable to the minutes … how do we create oral lang. experiences with the amazing ESL population? Any ideas? (OLP discussion forum, Are YOU talking less? In shorter sentences? Slower?)

Asking more questions to solicit responses. Most of the posted messages ended with a question like “Any thoughts?” or “Any ideas?” indicating the participants’ openness to each other’s opinions. It seems that adding an inquiry at the end of a message increased its chance of receiving a response. However, this strategy alone could not always save a discussion thread.

Argumentation. Only one discussion thread contained a slight conflict of ideas. The starting message was about schools that have finished their first 5 years in the Literacy Project, and the writer wondered if these schools would continue implementing the key themes of the project, specifically with regard to assessment. In her response, a mentor argued that only those teachers who did not believe in the value of continuous assessment might return to their original ways of teaching. The conversation ended there with no response or thoughts from other participants.

Theresa: What sorts of thoughts are folks having regarding the 5 Year itch…I’m thinking about the teams of teachers who are just counting the days when the 5th year of the project is done so they can just stop all this DRA’ing stuff/small group instruction/school wide writes etc and get back to their old ways of teaching…. What are we … doing about this?

Rachel: I’m wondering if people who are expressing concerns re having put in their time, have ever really bought into the goals and beliefs of the Literacy Project. For most teachers who buy into it, they could never go back to the way “it used to be”, nor can they remember what that was like.… It’s very sad to think some people miss out on this valuable part of making our instruction fit students’ needs. (OLP discussion forum, Grades K-3 Discussions, The 5 year itch!)

This instance touches on an important issue. During the interviews, one coordinator talked about her school staff that was somewhat tired of the additional burdens of the Literacy Project. She never used the discussion forum, however, and consequently was not aware of such a debate. Had she read the conversation between two seasoned Literacy Project mentors, she could have shared her own concerns about this issue.

Conclusion and Implications

OLP is the first attempt to investigate the role that online technologies could play in increasing professional development opportunities for the Literacy Project teachers. The current version of OLP has a general focus on literacy. The participants did not use the discussion forum to address those issues even though online communication could have facilitated their work. In this case, having a shared interest in the Literacy Project appeared insufficient to give direction to the development of the online component. From the beginning, the participants had different opinions about the perceived goal and focus of OLP and did not reach a consensus during the course of this study.

As for participation in OLP, it is important to consider how the participants found their online discussions meaningful to their professional development and relevant to their practice. It was evident that lack of focus strongly affected commitment to participation. Similarly, the participants found the OLP loosely relevant to their urgent teaching and learning agendas. During the study, the participants read the new messages and responded if they were interested in continuing the discussion. Yet they did not regard those communications as vital for their professional development or as having a substantive effect on their practice. Finally, participation in the discussion forum did not last beyond the time of this study, and the participants stopped contributing to the discussion forum before the study concluded. Clearly, the OLP did not become a functional Web-supported community primarily because the participants did not identify or agree upon a shared need for it.

Before embarking on this study, it was assumed that the OLP innovation could significantly facilitate the Literacy Project and that online discussions would grow steadily over the course of the study. That assumption was based on the fact that the Literacy Project teachers had a strong face-to-face community, which many researchers identify as a precondition for development of Web-supported TPD communities (Barab et al., 2004; Klecka et al., 2005; Schlager & Fusco, 2004).

This study serves as an important caution to those undertaking similar initiatives and brings to bear critical dimensions of such initiatives, some previously recognized and others that are only now beginning to emerge in the literature on Web-supported TPD. Specifically, lessons learned from OLP present five major cautions to be considered.

Lack of a Negotiated Need

The idea for the OLP was conceived in a dialogue among three members of the Literacy Project and two professors from a local university. The Literacy Project members who participated in this study assumed some need for an online component to be added to the Literacy Project, but they had never discussed or negotiated this need amongst themselves. Even in the case of strong face-to-face communities there is a need for coming to an explicit consensus about the objectives of adding an online component. Such clarifying negotiations would be more informed if stakeholders from different levels of the face-to-face community were involved. Also, meaningful activities strongly tied to the activities of a face-to-face community should be designed to scaffold participation in the Web-supported component. It is highly critical to the success of the endeavor to increase gradually community members’ ownership toward the online component and give them a leadership role in the development and evolution processes (Barab et al., 2001; Schlager et al., 2002).

Teachers’ Tendency to Search and Ask Rather Than Add and Respond in Online Environments

Despite considerable efforts to familiarize the participants with the various online elements of OLP, one of the main stumbling blocks for its evolution as a viable component of TPD was their reluctance to generate knowledge (Lave & Wegner, 1991), that is, to add and respond to the various discussion threads. Many of the participants recognized the discussion forum as only a place to ask questions from experts. Unfortunately, due to the limited scope of this study, it was not feasible to further investigate the assumption of less expert teachers’ having a minimal role in building the knowledge base of the profession. Klecka et al. (2002) suggested that one way to change the paradigm of teachers asking and experts answering in online settings is to explicitly remind teachers that they can break out of conventional expert-novice frameworks. Yet, success of this strategy depends on how much teachers see their online communications affecting their face-to-face community and how much they find online settings a safe space for reflecting on their theories and practices about teaching and learning (in this instance, of literacy practices in the early elementary years of schooling).

Teacher Skepticism About Reliability and Validity of Online Communication

In spite of the paradigm shift in the approach to TPD toward giving teachers greater leadership roles in customizing TPD according to their needs (Huberman, 1992; Loucks-Horsley et al., 1998) and legitimizing the knowledge generated by teachers (Guskey, 2003), teachers in this study were skeptical about relying on an online discussion forum to get credible answers to their inquiries or to have in-depth critical discussions. There seemed to be a reliance on more traditional forms of TPD for providing these activities. As a result, participation in the online component was tepid, at best, over the course of the study.

The “Succession Crisis” Phenomena

Teachers invest their time on activities that have viable long-term benefit and support. They did not see the OLP as a sustainable initiative. In other words, they could not foresee reliable and ongoing support for OLP in the current Provincial climate, where education had suffered severe cutbacks and the teachers had just endured a long period of protracted industrial job-action. They saw OLP as a one-off, 1-year pilot with little possibility of district support or guaranteed leadership in the following years. Therefore, participation in OLP (and, in particular, the discussion forum) came to a halt before the end of the study. Without an anticipated future in the minds of the participants, OLP found itself an endangered species within the district’s overall TPD environment. There is no quick fix for this problem, because the sustainability of the majority of TPD technology integration initiatives often depends on external funding and grants, many of which accompany university-based research projects.

Considering teachers’ apprehension about such initiatives, it is doubtful that they will continue to invest their limited time to examine seriously the potential of Web-supported environments. The situation becomes more critical considering the fact that time is a precious commodity for teachers, and most of them have to use their time at home if they wish to be involved in Web-supported communities, such as was attempted with the Literacy Project community.

Lack of Organizational Infrastructure Support

OLP brought to light an unanticipated feature of the school district. The technical support group within the district rejected the OLP research team’s request for space on the school board server to host the Web site and the discussion forum. The technical support group, despite policy documents to the contrary, did not see themselves serving teachers and teacher professional development. Rather, they held themselves accountable for administrative services within the district. This perspective came as a surprise even to those in power within the school board and highlighted a serious systemic problem within the organization of the district. In need of server space, OLP was hosted by the local university. The outcome was that the mentors and coordinators felt little ownership for OLP and saw it as an outside initiative.

To avoid technological fragmentation, in which the technological infrastructure employed by each group within a large community differs from the other so much so that it becomes nontransferable, Schlager and Fusco (2004) recommended that technology integration initiatives always consider the bigger context where the initiative is implemented. OLP could perhaps be sustained if the district, the larger context in this case, agreed to provide technical support. However, without such support, the possibilities were extremely limited.

The development process of OLP, although far from successful, has significant implications for future research. Throughout this study, the research team tried to keep close contact with the participants to observe how a subgroup of the Literacy Project teachers use a Web-based structure to further the opportunities for professional development. Unfortunately, the current form of OLP did not significantly enhance the professional development of the Literacy Project teachers, even though many of these teachers initially acknowledged the potential of online communications.

To this end, a practical approach for developing a Web-supported TPD community, where the financial and technical support are temporarily provided by universities and research groups, maybe to employ an adaptation of a participatory design method for face-to-face communities (as described by Merkel et al., 2004). This method emphasizes empowering community members to identify the issues that can be facilitated by technology and to recognize the suitable technologies that might address these issues. That is, the agenda is set to a large degree by the end-users themselves. Possibly, when teachers become more knowledgeable about what kind of Computer Mediated Communication can facilitate their professional development and interaction, initiatives like OLP might develop as effective online extensions to other TPD endeavors.

References

Barab, S. A., & Duffy, T. M. (2000). From practice fields to communities of practice. In D. H. Jonassen & S. L. Land (Eds.), Theoretical foundations of learning environments (pp. 25-55). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Barab, S. A., MaKinster, J. G., Moore, J. A., & Cunningham, D. J. (2001). Designing and building an on-line community: The struggle to support sociability in the inquiry learning forum. Educational Technology Research and Development, 49(4), 71-96.

Barab, S. A., MaKinster, J. G., & Scheckler, R. (2004). Designing system dualities: Characterizing an online professional development community. In Barab, R. Kling, & J. Gray H. (Eds.), Designing for virtual communities in the service of learning (pp. 53-90). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barab, S. A., Kling, R., & Gray, J., H. (Eds.). (2004). Designing for virtual communities in the service of learning. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Barnett, M. (2002). Issues and trends concerning electronic networking technologies for teacher professional development: A critical review of the literature. Paper presented at the annual meeting of American Educational Research Association, New Orleans.

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32-42.

Clarke, T., Storlund, J., Wells, J., & Wong, G. (2004). Improving literacy standards through a systemwide approach to professional learning. Paper presented at the National Staff Development Council 2004 conference, Vancouver, BC.

Cuthbert, A., Clark, D. B., & Linn, M. (2002). WISE learning communities: Design considerations. In K. A. Renninger, & W. Shumar (Eds.), Building virtual communities: Learning and change in cyberspace (pp. 215-248). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fusco, J., Gehlbach, H., & Schlager, M. (2000). Assessing the impact of a large-scale online teacher professional development community. In C. Crawford et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education International Conference 2000 (pp. 2178-2183). Chesapeake, VA: Association for the Advancement of Computers in Education.

Guskey, T. R. (2003). Result-oriented professional development. In A. Ornstein, L. Behar-Horenstein, & E. Pajak (Eds.), Contemporary issues in curriculum (3rd ed. pp. 321-329). New York: Allyn and Bacon.

Harasim, L., Hiltz, S. R., Teles, L., & Turoff, M. (1997). Learning networks: A field guide to teaching and learning online. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Hargreaves, A. (2003). Teaching in the knowledge society: Education in the age of incertainty. New York: Teachers College Press.

Havelock, B. (2004). Online community and professional learning in education: Research-based keys to sustainability. AACE Journal, 12(1), 56-84.

Huberman, M. (1992). Teacher professional development and instructional mastry. In A. Hargreaves & M. Fullan (Eds.), Understanding teachers development (pp. 122-132). New York: Teachers College Press.

Klecka, K. (2003, April). Trust, safety, and confidence: Building the foundation for online interaction. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, IL.

Klecka, C., Clift, R. T., & Cheng, Y. (2005). Are electronic conferences a solution in search of an urban problem? Urban Education, 40(4), 412-429.

Klecka, C. L., Clift, R. T., & Thomas, A. T. (2002). Proceed with caution: Introducing electronic conferencing in teacher education. Critical Issues in Teacher Education, 9, 28-36.

Kling, R., & Courtright, C. (2004). Group behavior and learning in electronic forums: A sociotechnical approach. In S. Barab, R. Kling & J. H. Gray (Eds.), Designing for virtual communities in the service of learning (pp. 91-119). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lave, J. (1997). The culture of acquisition and the practice of understanding. In D. Kirshner & J. A. Whitson (Eds.). Situated cognition: Social, semiotic, and psychological perspectives (pp. 17-35). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lieberman, A. (1995). Practices that support teacher development. Phi Delta Kappan, 76(8), 581-596.

Loucks-Horsely, S., Harding, C. K., Arbuckle, M. A., Murray, L. B., Dubea, C., & Williams, M. K. (1987). Continuing to learn: A guide for teacher development. Andover, MA: The Regional Laboratory for Educational Improvement of Northeast and Islands.

Loucks-Horsley, S., Hewson, P. W., Love, N., & Stiles, K. E. (1998). Designing professional development for teachers of science and mathematics. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, Inc.

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G.B. (1999). Designing qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Merkel, C. B., Xiao, L. Farooq, U., Ganoe, C. H., Lee, R., Carroll, J. M., & Rosson, M. B. (2004, July). Participatory design in community computing contexts: Tales from the field. In Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference 2004 (pp. 1-10). New York: Association for Computing Machinery

Merriam, S. B. (1988). Case study research in education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc., Publishers.

Muscella, D., & DiMauro, V. (1995). Talking about science: The case of an electronic conversation. Cambridge, MA: TERC Communications.

Reynolds, E., Treahy, D., Chao, C., & Barab, S. (2001). The Internet learning forum: Developing a community prototype for teachers of the 21st century. Computers in the Schools, 17(3/4), 107-125.

Schlager, M., & Fusco, J. (2004). Teacher professional development, technology, and communities of practice: Are we putting the cart before the horse? In S. A. Barab, R. Kling, & J. Gray (Eds.), Designing for virtual communities in the service of learning (pp. 120-153). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Schlager, M., Fusco, J., Koch, M., Crawford, V., & Phillips, M. (2003, June). Designing equity and diversity into online strategies to support new teachers. Paper presented at the National Educational Computing Conference, Seattle, WA.

Schlager, M. S., Fusco, J., & Schank, P. (2002). Evolution of an online education community of practice. In K. A. Renninger & W. Shumar (Eds.), Building virtual communities: Learning and change in cyberspace (pp. 129-158). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Selwyn, N. (2000). Creating a ‘connected’ community? Teachers’ use of an electronic discussion group. Teachers College Record, 101(4), 750-778.

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Zhao, Y., & Rop, S. (2001). A critical review of the literature on electronic networks as reflective discourse communities for inservice teachers. Education and Information Technology, 6(2), 81-94.

Author Note:

Hedieh Najafi

Ontario Institute for Studies in Education/University of Toronto, Canada

[email protected]

Anthony Clarke

University of British Columbia, Canada

[email protected]

![]()