English language arts (ELA) preservice teachers deserve experiences with new technologies, multimodality, and the arts because these areas offer valuable tools for communication in the 21st century. Through firsthand experiences with these tools (as well as opportunities to discuss pedagogical implications), preservice teachers can begin to think about how they might inspire creativity in their students while also meeting standards.

Since it is impossible to accurately predict what knowledge or information will be needed in the long-range future, it is important to focus on the development of skills which help individuals become more adaptable to new and changing circumstances. The ability to use knowledge is more generalizable and more widely applicable than memorization and recall of data. Skills and abilities are more permanent and related to the process of solving problems. (Isaksen & Murdock, 1993, p. 19)

Students need to have experiences with a range of tools. They will also benefit from teacher guidance as they practice combining and matching these tools to particular rhetorical situations.

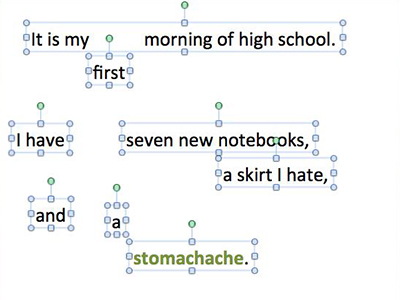

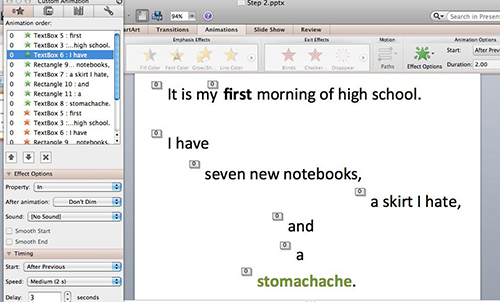

This article discusses the arts, multimodality, and technology in English language arts and then describes an example of a project that draws on all three, an “illuminated text.” An illuminated text is a slideshow consisting of animated text boxes. These projects are typically made using PowerPoint or the presentation program available through Google Docs. Essential quotes from a text move in and out of the screen. Adjusting the words’ colors, sizes, fonts, arrangements, timings, and movements illuminates the written text in meaningful ways. These projects are set to music, and they can also contain images.

Illuminated texts are useful for preservice teachers to know about because they can be used to reinforce content learning, support problem solving, and encourage communication through multiple modes. These projects provide a platform for students to think creatively as they weave together different art forms through technology. This sort of blending is a growing phenomenon in our postmodern culture. Remixing videos, music, and art is a popular practice (Lankshear & Knobel, 2011).

When students take up the challenge of constructing illuminated texts, they synthesize written text, music, and visual design. The experience not only heightens their awareness of the various art forms involved, but the final product becomes a work of art in itself. The incorporation of illuminated text projects in teacher education can help preservice teachers see the potential of the arts, multimodality, and technology in ELA. These multimodal projects demonstrate that with new technologies come new possibilities for the arts and multimodality in ELA.

The Arts, Multimodality, and New Technologies

Grouping the arts, multimodality, and new technologies together is not new. After all, discussion of one of these areas often flows into another. Albers and Harste (2007) brought these topics together in a coedited issue of English Education (Theme: “The Arts, New Literacies, and Multimodality”), as did Albers and Sanders (2010) in their coedited book, Literacies, the Arts, and Multimodality. Additionally, the Commission on Arts and Literacies, a subgroup of the Conference on English Education and the National Council of Teachers of English, exists to support the integration of the arts, multimodality, and new literacies into ELA.

The Arts

Albers and Harste (2007) wrote, “‘The arts’ often refers to the visual, musical, and performance arts, including paintings, ceramics, photographs, films, plays, storytelling, concerts, and others; the term is often associated with the word aesthetics” [emphasis in original] (p. 8). This description highlights several places where the arts overlap with ELA. A written text may culminate in a film, be performed on stage, or be set to music.

Benefits of the Arts. In The Arts and the Creation of Mind, Eisner (2002) discussed several cognitive benefits of the arts. He wrote that the arts can “help us learn to notice the world,” “engage the imagination as a means for exploring new possibilities,” help us “tolerate ambiguity,” and “discover the contours of our emotional selves” (pp. 10-11). These benefits—perception, creative problem solving, tolerance for ambiguity, and self-awareness—share much in common with ELA goals for reading, writing, listening, and speaking.

Consider the similarities between a photographer’s trained eye for detail and a writer’s selection of vivid details or a reader’s close reading of a text. Attention to detail is necessary in many practices, and the arts can help foster this skill. As an illustration of this overlap, one need only consider the example of New York City police officers participating in an “Art of Perception” course at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in order to “sharpen [their] observation skills” (Hirschfeld, 2009, p. 49). Apparently, learning to pay attention to details in paintings helped these officers give better descriptions in their reports, notice criminal behavior in crowded areas, and search crime scenes more effectively. Of course, the arts can also be used to develop imagination and creativity (Greene, 1995; Robinson, 2011).

Using the arts in ELA can help students draw on multiple languages for sharing their stories. Sanders and Albers (2010) wrote, “The arts encourage a different type of language learning, one that enables children to authentically tell their cultured stories, to speak through art, and to understand stories more deeply through informed viewing of art” (p. 8). The arts expand possibilities for communication.

Because objects of art are expressive, they are a language. Rather they are many languages. For each art has its own medium and that medium is especially fitted for one kind of communication. Each medium says something that cannot be uttered as well or as completely in any other tongue. (Dewey, 1934, p. 110)

In ELA classes, which seek to support and stretch students’ communication skills, the arts are attractive because they provide additional avenues for expression. Artists communicate through visual, verbal, musical, and physical means (John-Steiner, 1997; Robinson, 2011). The languages they use, which embody unique tools and histories, enable different modes of communication. One need only compare pieces composed of different materials. A Renaissance oil painting can communicate texture (Berger, 1972) quite differently than an essay can.

New possibilities for matters of representation can stimulate our imaginative capacities and can generate forms of experience that would otherwise not exist….Each new material offers us new affordances and constraints and in the process develops the ways in which we think. There is a lesson to be learned here for the ways in which we design curricula and the sorts of materials we make it possible for students to work with. (Eisner, 2003, p. 381)

Materials are an important consideration in curriculum planning because they pave the way for different kinds of experiences. In ELA classes, the materials that are available to students will influence how communication and learning occur.

Finally, experiencing the arts can broaden students’ education and help them realize their creative potential. Csikszentmihalyi (1996) pointed out that “a person cannot be creative in a domain to which he or she is not exposed” (p. 29). Also, Robinson (2011) wrote that each discipline

reflects major areas of cultural knowledge and experience, to which we all should have equal access. Each addresses different modes of intelligence and creative development. The strengths of any individual may be in one or more of them. A narrow, unbalanced curriculum will lead to a narrow, unbalanced education. (p. 273)

Students of all ages deserve to have experiences across the disciplinary spectrum, which includes having a chance to experience the arts.

Integrating the Arts Into English Language Arts. Teachers are integrating the arts into ELA classes in creative ways. Albers and Sanders (2010) documented some of the ways teachers and students are engaging in various art forms alongside literacy learning. ELA classes are engaging with opera and fairy tales (Blecher & Burton, 2010), filmmaking and short stories (Robbins, 2010), drawing and essay writing (Zoss, Siegesmund, & Patisaul, 2010), and visual texts and novels (Albers & Sanders, 2010).

Another collection documenting the power of the arts in ELA is the Handbook of Research on Teaching Literacy Through the Communicative and Visual Arts (Flood, Heath, & Lapp, 2008). This volume demonstrates how drawing can help at-risk students learn (McGill-Franzen & Zeig, 2008), how digital storytelling (Robin, 2008) and drama (Galda & Pellegrini, 2008) can be used in the classroom, and how differentiated instruction can work with visual, communicative, and performing arts (Lapp, Flood, & Moore, 2008). These collections make a convincing case for the educative power of the arts.

Robinson (2011) claimed that teachers can help students develop their creativity by being encouraging, identifying creativity in students, and providing activities that “encourage self-confidence [and] independence of mind” (p. 270). In fact, Robinson’s presence as a keynote speaker at the 2012 National Council of Teachers of English conference—met by a packed house of enthusiastic teachers—may signal a shift in the field of ELA. In the midst of an era of standardization, supporting students’ creativity remains an important goal for many teachers. Integrating the arts into ELA is a step toward this goal.

When teachers integrate arts activities into ELA, they can expand students’ understandings of historical context, spark imaginations, help students see similarities and differences between art forms, and engage multiple intelligences (Gardner, 1983). The arts can help students experience the world vividly—with all of their senses—as they construct meaning and communicate messages.

The Arts in Teacher Education. Some teacher educators worry that the standardization movement and budget cuts have resulted in decreased arts education across the country. Ravitch (2010, drawing from Haney, 2000) explained how standardization has affected education in Texas, for example:

As teachers spent more time preparing students to take standardized tests, the curriculum was narrowed: Such subjects as science, social studies, and the arts were pushed aside to make time for test preparation. Consequently, students in Texas were actually getting a worse education tied solely to taking the state tests (p. 96).

Ravitch argued that in the face of increasing pressure to raise test scores schools may be tempted to cut any subjects seen as extraneous to the test, and such cuts can do real harm.

Additionally, there is growing concern that access to arts education is unequal. Ruppert (2009) urged schools to “level the playing field to help close the arts education achievement gap,” explaining that “minority students and those from low-income households have less access to instruction…[and] are less likely…to take field trips or have visiting artists in their schools” (p. 3). Robelen (2012) pointed out that music and visual arts access in high-poverty secondary schools has dropped from a decade ago.

Some teachers have responded to changes in arts availability at their schools by incorporating arts education into their own subjects (Holcomb, 2007). English educators can support teachers in this work by putting them in touch with professional resources and organizations. Changing Education Through the Arts and the Arts Education Partnership offer materials to support this goal. (Editor’s note: Website URLS can be found in the Resources section at the end of this article.)

In fact, the Arts Education Partnership has posted The Arts and the Common Core Curriculum Mapping Project, a document containing an abundance of teaching suggestions for using the arts in K-12 ELA curriculum. This easy-to-use resource helps teachers incorporate art, film, and music into their ELA classrooms while simultaneously meeting standards. Preservice teachers could be encouraged to refer to this document as they engage in curriculum planning activities.

Many other resources are available to support the integration of the arts into ELA programs. Burnaford’s (2007) Arts Integration Frameworks, Research, and Practice: A Literature Review explored integration practices for multiple arts, drama, dance, visual arts, and music. Additionally, Deasy’s (2002) Critical Links: Learning in the Arts and Student Academic and Social Development presented dozens of studies that show the impact of the arts on students. ArtsEdSearch, a database of studies related to arts education, is useful for education scholars.

The Conference on English Education’s Commission on Arts and Literacies group was founded in 2004 to support the use of the arts—as well as multimodality and new literacies—in English language arts. Members meet annually at the National Council of Teachers of English Conference.

In addition to becoming familiar with these resources, English educators might also see what local arts organizations have to offer. In my courses at Arizona State University, for example, I encourage preservice teachers to attend an Art + Writing workshop offered by the Phoenix Art Museum. Museum instructors connect teachers to works in the museum, provide sample lessons and materials, and demonstrate how various arts activities align to ELA Common Core State Standards. Sometimes superb resources are closer than we think.

Multimodality

While the presence of the arts in ELA usually involves integrating one art form at a time (e.g., drama, dance), multimodality implies that a message or composition consists of multiple modes (e.g., visual, auditory) at once. These two concepts can overlap, as an art form such as music, drawing, or photography may be one of the modes in a multimodal composition.

As Kress and van Leeuwen (2006) explained, “Any text whose meanings are realized through more than one semiotic code is multimodal” (p. 177). Additionally, “all meaning-making is multimodal. All written text is also visually designed” (New London Group, 1996, p. 81). Kress (2008) argued, “In a multimodal text, each modal component carries a part only of the overall meaning of the text” (p. 99). He also drew attention to differences across modes. Every mode contains both possibilities and limitations, and educators should consider what a particular mode can accomplish and what it cannot.

Siegel (2012) pointed out that multimodality is not new. It existed long before the Internet. She cited illuminated manuscripts and picture books as examples of hybrid texts that bring together visual art and written words. Multimodality is all around us—in our conversations, in the television programs we watch, on the Internet, and even in the books we read.

Nonfiction books commonly contain not only text and photographs these days but also links to instructional videos. How to Create Stunning Digital Photography (Northrup, 2014) is just one example of this phenomenon. Multimodal texts like this one offer multiple “reading paths,” opening up a range of possibilities for ways the reader moves through the text (Kress & van Leeuwen, 2006). That is, a reader of Northrup’s photography book might watch an instructional video for the book only after reading the corresponding section of text; another person might watch all of the videos first or save them all for last.

Benefits of Multimodality. One benefit of combining multiple modes, as in digital storytelling, is that the multimodal composition speaks to the audience through several different languages, creating a unique message overall. The layered result of a multimodal composition provides a different experience than, say, a traditional story. Eisner (2002) wrote, “In a metaphorical sense, becoming multiliterate means being able to inscribe or decode meaning in different forms of representation” (p. 22). Multimodal composition makes this demand.

Many literacy educators have argued that multimodal literacy is an important part of being literate in today’s world. “Movement across and understanding of the affordance of modalities…is the essence of what literacy—and the power of being literate—is all about” (Harste & Albers, 2007, p. 4). In reviewing the literature on multimodality, Siegel (2012) found three main arguments for multimodality in use:

- Literacies are changing, and so must school literacy curricula (p. 672).

- Youths bring multimodal practices to school (p. 673).

- Multimodal practice can reframe at-risk students as learners of promise (p. 674).

It is no wonder that multimodal projects are gaining popularity within ELA.

Digital storytelling, in particular, brings together “the art of telling stories with a variety of multimedia, including graphics, audio, video, and Web publishing” (Robin, 2008, p. 429). Robin found that when students used digital storytelling, they improved at many kinds of tasks, specifically research, writing, organization, technology, presenting, interviewing, interpersonal interactions, problem solving, and assessment (p. 433). Multimodal projects seem to offer a variety of benefits.

These projects also allow students to take control of their learning, as described by Albers and Harste (2007):

Design is one of the most important parts of multimodal expression because it encourages imagination, vision, and problem solving….In most school settings, teachers are the designers of the product, and students are the producers who try to create the design that the teacher has in mind. When students are both designers as well as producers, strong principles of learning can emerge through design. The learner must consider the message she or he wants to communicate, the materials that will offer the most potential in conveying it, and how viewers will respond. (pp. 13-14)

Multimodal assignments put students in charge of their learning.

Integrating Multimodality Into English Language Arts. Multimodal projects can take a variety of forms in the ELA classroom. Sewell and Denton (2011) have used public service announcement podcasts, an imaginary holiday complete with artifacts, and a music hall of fame research project. Hill (2014) has used a “Tour Across America [project, which] allows students the opportunity to become concert tour managers for a fictional band that is preparing to embark on a yearlong U.S. concert tour” (p. 453). This interdisciplinary project requires students to consider geography, research cities, develop a business plan, use mathematics, and write persuasively.

Teachers can empower students when they show how different modes work and then provide opportunities for students to compose using these modes. Students also need experiences reading multimodal texts. Harste (2010) discussed a useful framework for reading multimodal texts, focusing on “language, vision, and action” (p. 33). English educators can prepare preservice teachers for this work by providing them with experiences reading and composing multimodal texts.

Siegel (2012) acknowledged that some teachers may be hesitant to embrace multimodality in the current accountability culture. She pointed out the paradox: There are “two colliding storylines—the expansion of modes for meaning making, and the confinement of this multiplicity through the practices of accountability” (p. 675). As a way to reconcile these two storylines, Siegel suggested (drawing from Albers, Holbrook, & Harste, 2010) that teachers and students engage in “trade talk.” Siegel said trade talk “is largely reflective talk—that is, talk about the art they have made—and it serves both a heuristic and communicative function” (p. 676). Trade talk can be a component of multimodal project assessment at both the secondary and college levels. Having students articulate their decision-making helps the artist reflect, but it also provides an additional artifact to document the learning that has taken place.

Furthermore, Benson (2008) recommended “meta-cognitive conversations” in order to support “a change of thinking about literacy instruction” (p. 667). She explained, “Larger curricular goals need to be made clear for students so that they have an opportunity to move beyond a mindset of assignment completion and think about how multimodal thinking fits into broader communication purposes” (p. 665). In other words, integrating multimodality into ELA is not enough. Teachers must also help students see why this work is important.

Benson found that the students in her study tended to privilege written text. To disrupt this hierarchy, students should consider “what they are specifically communicating and how [that fits] a given audience at a given time” (p. 666). Teacher educators can help preservice teachers prepare for this work by asking them to create multimodal projects (to give them firsthand experience working with the tools) and then asking them to explain their choice of modes for that particular rhetorical situation (reinforcing the value of nonprint modes).

Multimodality in Teacher Education. Multimodal projects are becoming more common in teacher education programs across the country. Suzanne Miller (2007) described some of the work being done by the New Literacies Group at the University of Buffalo and with the Buffalo City School District. Teachers and preservice teachers work together, reading theory, engaging in discussions, and making their own digital video projects. She found that students who were involved with making digital video projects benefitted tremendously: “Clearly, these students were drawing on their lifeworlds as resources in their [digital video] composing, but also critiquing those lifeworlds, reframing neighborhood identities, and using their collaborative work as a persuasive move aimed at change” (p. 77). Those projects motivated students to examine their situations critically and imagine new possibilities. (See Miller, 2010, pp. 274-275, for teaching considerations.)

Multimodality has also been integrated into the University of Minnesota’s English education program in creative ways (Doering, Beach, & O’Brien, 2007). Their preservice teachers were assigned to middle school students, and they used digital mapping tools, worked on an urban neighborhood project, and learned how to critically analyze various modes. The researchers found that preservice teachers in the program “learn[ed] to embed the use of these tools within inquiry-based activities” (p. 58). This study demonstrated the importance of having preservice teachers experience the multimodal tools they will ask students to use.

Albers (2006) has also demonstrated how multimodal training can work in a teacher education program. “Living through a multimodal curriculum—at the same time that they learn about [multimodality]—enables PSTs to conceptualize curriculum design from such a perspective,” she wrote (p. 80). Albers took preservice teachers through a unit on the Harlem Renaissance. Activities included watching a PowerPoint presentation, doing a gallery walk, reading a newsletter, and creating a book pass. Preservice teachers engaged with Harlem Renaissance artworks, music, novels, and picture books. They used transmediation, a technique “in which learners retranslate their understanding of an idea, concept, or text through another medium” (p. 90).

For example, a reader might take a concept from a book and represent it in clay. Preservice teachers also planned multimodal lessons and created their own cultural heritage projects. Albers immersed preservice teachers in deep content learning through multiple modes, and then she provided opportunities for reflection. These teachers learned to envision multimodal possibilities of content as they planned curriculum.

Miller (2013) found that several common features were present in the successful teaching of multimodal projects. Teachers needed opportunities to reflect and talk with each other, which helped them develop “their New Literacies stance and created resilience…as they solved problems” (p. 407). They “created classroom social spaces for mediating multimodal composing,” and “students and teachers co-constructed authentic purpose[s]” (pp. 407, 409). Additionally, multimodal projects invited students to bring their interests into the classroom, teachers specifically taught design elements, and students internalized their learning as they “transmediated” (p. 416). These findings offer a useful framework for teaching multimodality within English education.

In a study of multimodality at an urban school, Costello (2010) found that challenges could arise. A teacher might pull a video project from a class as punishment, seeing “drama and video as supplemental learning activities to be used as a reward for good behavior, rather than much-needed pedagogical tools with the potential to transform the everyday life of [the] classroom” (p. 249). Costello urged teacher educators to prepare teachers to use these tools. Harste and Albers (2007) also recommended that teacher education programs include firsthand experiences with the tools that secondary students will be expected to use.

Multimodality brings new opportunities and challenges to the teaching of ELA. Teacher education programs will need to not only give preservice teachers experiences with multimodal compositions but also prepare them to engage students in larger discussions about the selection of modes to best address particular rhetorical situations.

New Technologies

New technologies are changing how people communicate, creating new possibilities for the multimodal messages sent and received. According to Lankshear and Knobel (2011), “established social practices have been transformed” by new technologies, “and new forms of social practice have emerged and continue to emerge at a rapid rate” (p. 28).

They added that not only is technology itself changing, but a corresponding change in ethos is occurring as technologies become more interactive. Swenson (2006) suggested that these changes are creating opportunities for teacher educators to “identify new sites for [their] own and [their] students’ learning” (p. 167).

MacArthur (2006) wrote that past technological innovations (e.g., inventions like radio, television, and the movies) also influenced people’s lives; however, it does not necessary follow that changes in technology will have a corresponding effect on education. In fact, MacArthur argued, “The actual effects of the technology depend on complex interactions among the technology, the social context, and individual users” (p. 249). New tools have certainly changed our roles from “consumers” to “producers” (p. 248). In a Web 2.0 world, instead of merely reading encyclopedia entries, we can rewrite them. It seems that “each new tool subtly changes the practice” of writing (Bruce, 2007, p. 4).

Young, Dillon, and Moje (2007) wrote, “These new times are times of information density, rapid change, and fragmentation of identities and ‘shapes’” (p. 130). Lisa Miller (2007) suggested that jobs of the future will ask employees to use editing programs (e.g., video-editing), as companies will deliver more information through the Internet. Clearly, education must prepare students for a changing world. In a policy brief, the National Council of Teachers of English (2009) recommended that teachers help students:

develop proficiency with the tools of technology; build relationships with others to pose and solve problems collaboratively and cross-culturally; design and share information for global communities to meet a variety of purposes; manage, analyze, and synthesize multiple streams of simultaneous information; create, critique, analyze, and evaluate multi-media texts; [and] attend to the ethical responsibilities required by these complex environments. (p. 15)

Rhodes and Robnolt (2009) said that students should be able to work across different subject areas, come up with innovative solutions, and read online texts carefully and analytically. Furthermore, students should be able to interact with texts as “informed participants and critics” (Bruce, 2007, p. 18). They will write for various audiences, employing various forms (DiVito, 2011). Preservice teachers will need our help preparing to teach these skills.

Benefits of New Technologies. Technology can offer many benefits to students. According to a policy brief by the National Council of Teachers of English (2007), technology can make learning more interactive, and allowing students to write with computers can lead to longer and more sophisticated pieces. Many researchers have found that computers aid struggling students (MacArthur, 2006; Rhodes & Robnolt, 2009).

Technology can also provide excellent opportunities for students to publish their work (Rocco, 2011), as students connect to real readers around the world (Bruce, 2007) and go beyond one teacher as the main audience (Boardman, 2007). With digital video, in particular, students may “write themselves into the piece,…[take] pleasure in expressing themselves, [and be]…proud to share with their peers and parents” (Hughes & Robertson, 2010, p. 34).

Kajder (2007) claimed that technology can be used to support active participation and a positive classroom atmosphere, and it can even reveal students’ talents. Technology can also support students as they take on authentic roles like filmmaker and graphic artist, help teachers reach a wider range of students, and “give [students] a reason to really value what we do in English class” (p. 151).

Lisa Miller (2007) said that students embrace digital storytelling because “it’s active and visual and fun” (p. 174). On the other hand, some teachers use new technologies to teach critical inquiry (Beach & Bruce, 2007). Digital storytelling can help students see the world through new lenses.

Sanders and Albers (2010) said that “we develop new ways of being when working with new technologies: sharing, experimenting, innovating, and creative rule-breaking” (p. 11) Technology can also change the ways people interact (Bruce, 2007). Furthermore, new technologies transform people’s understandings of texts and readers, demanding a change in how teachers teach reading (Swenson, Rozema, Young, McGrail, & Whitin, 2005).

Integrating New Technologies Into English Language Arts. Technology can be integrated into ELA in a variety of ways. Many new programs are available beyond the word processing, spreadsheet, presentation, photo-editing, and movie-making programs that come standard on many computers. Adolescents and their teachers are going online, using blogs and wikis to share information (Lankshear & Knobel, 2011), Glogster to make multimodal posters (Campbell, 2011), and Lexipedia and Wordle to work with words (Shoffner, 2013).

They are using Storyspace for hypertext creation (Young & Bush, 2004), as well as ThingLink to make linked images, Storyboard That for storyboarding, Storybird for illustrating stories, and Capzles for interactive timelines (Shoffner, 2013). Additionally, students are able to make their own comic strips using sites like Bitstrips and Make Beliefs Comix.

Some teachers are using Moodle for class platforms and Edublogs for class blogging (Boardman, 2007). Teachers are building websites for online portfolios (Rhodes & Robnolt, 2009) and finding academic applications for social media tools like Twitter and Pinterest (Shoffner, 2013). For those just getting started with technology in ELA, Kajder (2007) recommended three relatively easy-to-use assignments: literature circle podcasts, class wikis, and fan fiction.

Hicks and Turner (2013) warned teachers against inserting technology in their lessons just to make them seem exciting. Instead, the technology should help students contribute to class discussions and activities and even change the course of what happens in class on a particular day. A good example of using technology to redirect what happens in class can be found in Hunter and Caraway’s (2014) discussion of Twitter use in the classroom. They found that Twitter made reading more interactive and class activities more responsive to students, which in turn increased student motivation.

Hinchman and Lalik (2007) suggested that it is only fair for teachers to be familiar with the technologies they ask students to use. Teachers should also be open to learning with students. Kajder (2007) wrote, “It’s about doing new things with new tools alongside our students” (p. 161). King and O’Brien (2007) concurred: “We suggest that teachers and students collaboratively learn the ‘new literacies’” (p. 43). Hagood, Stevens, and Reinking (2007) saw “a need to rethink ways to involve adolescents in both the teaching and learning of contemporary literacies and to acknowledge their knowledge and power” (p. 82). Students have much to offer.

New Technologies in Teacher Education. Teacher educators have much to consider when it comes to integrating technology into ELA programs. Shoffner (2013) recommended taking a three-pronged approach: (a) “Implement [technology] into our own teaching,” (b) “Integrate it into our coursework,” and (c) “Invite it into our thinking” (pp. 101-102). Teacher educators should also seek out ways to use technology to connect preservice teachers and secondary students. For instance, preservice teachers could use social networking tools to engage high school students in discussions about the literature they are reading in class (Nobles, Dredger, & Gerheart, 2012).

Teachers must be prepared to integrate technology into their classrooms in responsible ways. Young and Bush (2004) wrote, “The power of the pedagogy must drive the technology being implemented, so that instruction, skills, content, or literacy is enhanced in some meaningful way. Otherwise, the technology itself often becomes the content focus rather than the English language arts” (p. 8). Said another way, “Digital tools are only as useful as the objects or outcomes they are designed to serve” (Beach & Bruce, 2007, p. 162).

In methods courses, teacher educators can take preservice teachers through the process of designing content objectives and then ask them to consider which tools might best help them achieve these goals. Swenson, Rozema, Young, and colleagues (2005) referred to this action as “purposeful integration” of technology (p. 229). In addition to learning about multiple tools and experiencing them firsthand, preservice teachers need to think through the advantages and disadvantages of the tools they select (Swenson et al., 2005).

Several resources exist for thinking through the use of technology in the classroom. Young and Bush asked several questions, including the following:

- “Why do I want to use technologies?”

- “How might issues of access and equity affect our experience?”

- “How will the use of technology affect or enhance my students’ overall literacy?” (2004, pp. 10-11).

Kajder asked, “What are the unique capacities of this tool?” and “What does it allow me to do that is better (instructionally) than what I could do without it?” (2007, p. 152). Beach and Bruce also provided a series of questions, including, “Are students using tools to actively produce texts or hypertexts in ways that lead them to interrogate those texts?” (2007, p. 163). In an ELA methods course, any of these question sets could be used to guide preservice teachers as they think through the use of technology in particular pedagogical situations.

The role of the teacher has changed in the 21st century, and the role of the English educator has changed as well. “English educators must integrate digital texts into the curriculum…encourage students to recognize, analyze, and evaluate connections between print and digital texts, as well as recognize what a reader of print and digital texts needs” (Swenson et al., 2005, p. 222). Preservice teachers will need experiences reading and composing many different kinds of texts.

Evaluation needs to be updated as well. Swenson et al. (2005) suggested that teachers “consider not only process and product, but also design elements, choice of artifacts, and critical connections and meaning-making” (p. 225). An expanded view of literacy requires a corresponding expansion of ELA goals and assessments.

Many resources exist to support the integration of technology into teacher preparation programs. For example, Jim Burke’s English Companion Ning is a place where teachers and teacher educators can come together to share ideas and help each other (Nobles, Dredger, & Gerheart, 2012). Teachingmedialiteracy.com—a companion site for Beach’s (2007) book by the same name—offers links to a wealth of resources. Also, the Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy features a Text Review Forum column that highlights visual and digital texts, a place to go to learn about new websites, applications, and programs.

In addition, websites are even available now that offer videos of teachers teaching; Sherry and Tremmel (2012) discussed several of these sites in detail, including Edutopia, the Gallery of Teaching and Learning, and Teacher Tube. Technology is transforming teacher education.

For those seeking to learn more about the integration of technology in teacher education, Swenson (2006) recommended attending the Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education (SITE) Conference. The Commission on New Literacies, Technologies and Teacher Education, part of the National Council of Teachers of English and the Conference on English Education, is another place to turn.

Of course, technology brings with it some challenges worth addressing in teacher preparation programs. Technology, indeed, is rapidly changing. “It’s hard to keep up, to keep pace; it seems like once we learn a new technology, it changes” (Groenke, 2011, p. 1). Because of this state of constant change, some scholars warn that “focusing on teaching new technologies rather than English language arts/literacy learning [would be] shortsighted” (Swenson et al., 2005, p. 217). Instead, technology needs to be taught in context (Swenson, Young, McGrail, Rozema, & Whitin, 2006). Another challenge with technology has to do with cost and, therefore, access. Teachers will need to be resourceful, locating free software when necessary (Swenson et al., 2005).

A third obstacle has to do with attitudes toward technology. Teachers may fear they are falling behind, that the generation gap between them and their students is large and growing larger. However, Lewis and Finders (2007) found that this sense of a gap is much more about teacher and student identities, especially in cases where teachers are closer in age to students and use many of the same technologies. Teacher educators can address this issue by helping preservice teachers appreciate the technological knowledge they already have.

Teacher educators can also help foster an attitude of open-mindedness and curiosity toward new technologies by giving preservice teachers access to various programs. Preservice teachers will need time to experience different technologies firsthand, time to evaluate the pedagogical usefulness of these technologies, and time to integrate the best tools into their lesson planning.

Illuminated Texts

Illuminated texts are useful in teacher education programs because they demonstrate the power of the arts, multimodality, and new technologies all at once. These slideshows, filled with animated text, music, and sometimes images, can be used as high-tech book reports or even presentations of students’ writing. (For a step-by-step guide to creating an illuminated text, see Appendix A.)

Several excellent examples of illuminated texts are available online. Deakin and Sindel-Arrington (2010) recommended Lee’s illuminated text for Hemingway’s short story “Cat in the Rain,” a project that uses color and animation in creative ways. Other examples available online include Etchart’s illuminated text of George Orwell’s 1984, which uses photographs (see Video 1).

Video 1. 1984 – Illuminated Text from Cameron Etchart on Vimeo.

One of my students made the Wintergirls illuminated text (based on Laurie Halse Anderson’s book), which is posted on the YA Lit-Tech Consortium website. This project is meant to be accompanied by Buckethead’s song, “Soothsayer.” Searching “illuminated text” in YouTube will yield additional examples. Teachers and students post projects all the time.

Illuminated texts are essentially multimedia book reports. Rhodes and Robnolt (2009) wrote that

multimedia book reviews…(1) allow students to use computers to include graphics and sound to enhance their textual information about a book; and (2) can be shared with more people than the students in a classroom because they can be posted on the Internet, making the reports available to a wider audience. (p. 165)

They suggested that multimedia book reviews can increase student interest, encourage students to read more, and motivate teachers to embrace new technology.

A form of digital storytelling, illuminated texts create a space where the arts, multimodality, and new technologies meet within ELA. Stories are shared in creative ways. Like digital videos, these high-tech book reports “[involve] aesthetic considerations; [also,] the power of moving images, sound, and music serves to rhetorically engage their audiences’ emotions and create involvement in narrative development” (Beach & Swiss, 2010, p. 302).

Because of these similarities, some of the work on digital storytelling also fits illuminated texts. For example, digital storytelling rubrics that include elements like audio, pacing, music, animation, content, and creativity (Beach & Swiss, 2010, p. 312) can be adapted to fit this project. Self-evaluation questions such as, “To what extent does the completed work fulfill your artistic intent?” (p. 314) may also apply. Lisa Miller’s (2007) description of how to teach digital storytelling—including having students gather materials, discuss audience, storyboard, compose (with earphones), and share draft versions—is instructive for illuminated texts as well.

Using Illuminated Texts With Preservice Teachers

The illuminated text project is an important assignment for preservice teachers for several reasons. Because the assignment brings together the arts, multimodality, and new technologies, it creates opportunities for discussions about design and aesthetics, the choice of modes for particular audiences and situations, and the possibilities that arise with new technologies. This project also inspires creative thinking, problem solving, and collaborative learning. Furthermore, the project aligns well to several Common Core State Standards.

I first used the illuminated text project with preservice teachers in my methods of teaching writing course at Arizona State University to demonstrate an example of writing with technology. We viewed some projects that my former secondary students created, talked about techniques they used, and continued our discussion into other ways technology is useful in the secondary ELA classroom. I also provided a handout of teaching suggestions. (See Appendix B.)

Looking back upon that semester, I see now that my identity in that course was one of a former high school teacher giving advice to future high school teachers. Rather than providing deep and meaningful learning experiences, I sometimes covered content too quickly, sharing materials that had worked for my secondary students. As Costello (2010) and Harste and Albers (2007) argued, teacher educators need to do much more. We need to provide opportunities for preservice teachers to engage with the tools students will be asked to use. Keeping this advice in mind, when I taught the course subsequently I completely changed the way I used illuminated texts with preservice teachers.

The second time I introduced illuminated texts, I had developed three key objectives. I wanted preservice teachers to extrapolate characteristics of illuminated texts by viewing several examples, to gain firsthand experience working with the technology, and to reflect on the usefulness of this assignment for their own students. We started by viewing the “Cat in the Rain” and Wintergirls illuminated texts, as well as an illuminated text for The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, a project by two of my former high school students. We took these projects one at a time, discussing features of each immediately after viewing them.

Preservice teachers noticed that the “Cat in the Rain” illuminated text used different colors for each speaker: pink for the wife and blue for the husband. They also commented on the project’s use of animation: the word rain was turned on its side and fell like rain, letters were pulled from many words to form the word attention, and words were placed in shapes to represent their spatial relationships. Preservice teachers seemed impressed by these design elements, and they were surprised to learn that all of this work could be done in a program like PowerPoint. Although PowerPoint was a familiar technology for them, none of them had ever used it in this way. We also talked about the choice of music for this project (i.e., the sound effects in the song complement the rain in the story) and the use of images (i.e., pictures of a cat and a couple are used at the end).

After we watched the Wintergirls illuminated text, one preservice teacher remarked that the music was distracting, but others retorted that the wailing guitar fit the dark mood of a book that deals with eating disorders and a girl’s untimely death. Critiquing some parts of the project’s design, some of them noticed that certain phrases took too long to appear. Overall, they said they were impressed that one high school sophomore was able to do so much with this project and that she seemed to have included the key moments from this book by Laurie Halse Anderson.

By the time we got to the illuminated text of Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian (Alexie, 2007), preservice teachers seemed to have a good idea of the possibilities and limitations of the various modes that work together in these multimodal projects. We talked about music and how the two students who created this project chose a song with lyrics, something I had advised them not to do but which turned out working really well in this case.

We talked about images, as this project incorporated drawings from Alexie’s book. I pointed out that the font size used in this project was smaller than in the other projects, but preservice teachers said it was not small enough to bother them. In fact, they liked that the students had included so much text from the book. They also commented on this project’s use of animation, noting that these two students had used advanced animation features, making the word hope grow larger as the me moved away from the word reservation as well as simulating a fight by having a me get bounced among several bullies.

Before they came to this class, I had asked the preservice teachers to read Lisa Miller’s (2007) chapter on digital storytelling in Teaching the Neglected “R,” so they could see how a digital project might play out in a secondary classroom. They had also written a poem during the previous class, and when it came time to build their own illuminated texts, they had the option to illuminate those poems. As an alternative, they could select one of the children’s picture books I had brought along, such as Goldilocks and the Three Bears.

Because we were spending only part of a 75-minute class making the projects (the first half was spent viewing and discussing examples), shorter texts like poems and picture books helped them quickly grasp the text before engaging in transmediation (Albers, 2006; S. Miller, 2013). I asked them to complete at least one slide in the 40 minutes. However, this was a loose guideline, as students could put as much or as little text on that slide as they wished. Several students were able to complete more than one slide in the allotted time. I was impressed by how quickly they selected key quotes from their chosen texts and figured out the technology.

My original plan was to have them play with the technology in class for a while and then, as a closure activity, write a reflection about how the assignment could be useful in their own classrooms. However, they were so engrossed in the task of making their projects—and they were having so much fun—that I let them work until that class ended. When they also said they wanted to share their projects at the next class, I rearranged the schedule to accommodate them.

At the next class, volunteers shared their projects. Some had illuminated their own poems, some had used the children’s books, and others had found published poems. They experimented with animation and selected music that matched the different moods of their texts. For example, one preservice teacher’s poem about an old friend was accompanied by the Friends television series theme song.

Another preservice teacher admitted she spent hours outside of class working on her illuminated text because she enjoyed the activity so much. Her illuminated text for the poem “The Quiet World” by Jeffrey McDaniel was spectacular. When I used illuminated texts as a high school teacher in 2011, sophomore English students created projects for the young adult novels they were reading. However, after observing the success preservice teachers had illuminating poems, I am convinced that if time is limited, short texts substitute well.

After we finished viewing their projects, I asked them to reflect on the following questions:

- What did you like about this activity?

- How could this activity be of use to students?

- What was challenging, and how did you work through it?

They wrote out their responses, and the questions guided us in a “meta-cognitive conversation” (Benson, 2008) about the teaching of illuminated texts. Adding a fourth question about artistic intent may have encouraged a greater degree of “trade talk” (Siegel, 2012, drawing from Albers et al., 2010).

The preservice teachers described this activity using words like fun, awesome, so cool, new, interesting, creative, and artistic. Their responses reminded me of Lisa Miller’s (2007) claim that students enjoy digital storytelling because “it’s active and visual and fun” (p. 174). One preservice teacher pointed out that it forced him to pay more attention to language and its place in the larger text. Another person enjoyed depicting emotion through color and animation.

Several students in the class mentioned that the assignment helped them see the original text in a new way or it helped bring the text to life. They also said there were many things about the assignment that would be useful for their future students. Specifically, they appreciated that illuminated texts support the development of technological skills, visual literacy, close reading, and personal meaning making.

Their responses bring to mind Eisner’s (2002) list of the cognitive benefits of the arts, especially that the arts can “help us learn to notice the world,” “engage the imagination,” and “discover the contours of our emotional selves” (pp. 10-11). Robinson (2011) recommended that teachers develop students’ creativity through activities that “encourage self-confidence [and] independence of mind” (p. 270).

Although the preservice teachers reported that the biggest challenge was figuring out the technology in the allotted time, they all managed to create a slide by the end of class. If I were to use this assignment again, I would have our class meet in a computer-mediated classroom on campus, where all students would have access to PowerPoint. I would also have them practice creating a text box and animating it before setting them free to make their own slides.

Because we were working in a nonmediated classroom, students brought their laptops. Some had PowerPoint, and others turned to the free presentation program available through Google Docs. It was powerful watching students supporting each other as they figured out Google Docs together. In line with recommendations by Kajder (2007), King and O’Brien (2007), and Hagood, Stevens, and Reinking (2007), I wanted to honor preservice teachers’ knowledge as we collaboratively worked through the challenges that come with making illuminated texts. They naturally jumped in and helped each other, excited to demonstrate what they had figured out.

The next time I use this assignment with preservice teachers, I will set aside more time for making and sharing projects, as well as time for deeper discussions about the potential of this assignment for bringing together the arts, multimodality, and new technologies. In regard to the arts, the illuminated text project provides an excellent medium for synthesizing various art forms. Students can also integrate their original pieces (e.g., their own poems, photographs, drawings, paintings, songs). Constructing these projects requires creativity in design as well.

These projects provide opportunities for thinking more about multimodal composition, including the possibilities and limitations of each mode involved (Kress, 2008). Kress called for “a new awareness in the use of representational resources” (p. 99), and illuminated texts can be used to draw attention to the contributions of songs, animations, images, and texts. Moreover, there is room for students to compare a project to the original text from which it derives.

For example, my former secondary students watched the illuminated text for “Cat in the Rain,” read the Hemingway story it is based on, and then compared these two texts. I asked, “What is gained as the story becomes an illuminated text, and what is lost?” and “How might the illuminated text help us re-envision new possibilities for communication?”

The illuminated text allows students to take a familiar technology (i.e., Powerpoint) and do something new with it. Although teachers and students may claim that they are not tech savvy, they will feel differently once they have created an illuminated text and shared it with others. As Hughes and Robertson (2010) found with digital video projects, students are excited to share their projects with others. The National Council of Teachers of English (2009) recommended that teachers help students “develop proficiency with the tools of technology.…build relationships with others to pose and solve problems collaboratively…[and] create, critique, analyze, and evaluate multi-media texts” (p. 15). When preservice teachers construct illuminated text projects, they can see how these goals might come together in a real assignment. This work is also in line with Shoffner’s (2013) recommendation that English educators develop assignments that give preservice teachers experiences with new technologies.

Alignment to the Common Core State Standards

One aspect of illuminated texts that teachers will appreciate is these projects fit well with the Common Core State Standards (Common Core Standards Initiative, 2014). For example, consider the fifth speaking and listening anchor standard of the English Language Arts Standards, which reads, “Make strategic use of digital media and visual displays of data to express information and enhance understanding of presentations.” This standard is addressed as students compile their presentations. They become more familiar with the capabilities of presentation software (especially the animation features of slideshow programs), building technological knowledge as they also build their illuminated texts.

Albers and Harste (2007) argued that students learn a lot more when they have control over how a project is designed. When students make illuminated texts, they select tools to best communicate messages to their audiences, and they must think like designers as they weigh various options and deal with any problems that arise.

Multiple reading anchor standards can also be addressed using this project. These standards ask students to

- Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text. (1).

- Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas. (2).

- Analyze how and why individuals, events, and ideas develop and interact over the course of a text. (3).

- Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone. (4).

- Analyze the structure of texts, including how specific sentences, paragraphs, and larger portions of the text (e.g., a section, chapter, scene, or stanza) relate to each other and the whole. (5)

- Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text. (6)

- Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse formats and media, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words. (7). (Common Core Standards Initiative, 2014).

Before they make illuminated texts, students collect evidence from the book (or other text) and make inferences (Standard 1). Teachers might have students record this work in the form of quotation logs. A good illuminated text will also reveal the student’s understanding of the text’s theme, characters, and point-of-view (Standards 2, 3, and 6).

The illuminated text project is particularly well suited for addressing standards that deal with language (Standards 4 and 5). The close reading required in making an illuminated text has students attend to the connotations of words, consider how words and phrases contribute to tone, and how an excerpt connects to other parts of the same text.

As students critique illuminated texts, the last standard in this list is addressed (Standard 7). Specifically, students evaluate sample presentations at the beginning of the unit, and later they evaluate their peers’ projects. Each time, they must deconstruct the project enough to determine what is working and what is not. While these standards would be addressed to different degrees depending on how the project was taught, the illuminated text demonstrates that teachers can integrate experiences with the arts, multimodality, and new technologies in ELA while simultaneously meeting standards.

Discussions with preservice teachers about how illuminated texts support Common Core State Standards would be useful. Preservice teachers could also design supplemental assignments to support students in meeting the reading standards. For example, students would benefit from short journal entries or discussions on theme, character, and point-of-view. In fact, this work could take place at any point in the unit (e.g., when students are deep in the reading, after they have finished their book, after they have created a rough draft of the illuminated text, or when they have finished the final version).

Preservice teachers might also consider how an assignment like the illuminated text would be graded. How would the rubric reflect standards? And what other considerations—especially aesthetic, multimodal, and technological—might teachers include in this rubric? In addition to designing a rubric, preservice teachers could create a project evaluation form to help guide students as they evaluate their own and others’ projects. Making these materials would help preservice teachers prioritize the learning outcomes for the unit.

Conclusion

In addition to its usefulness for supporting standards, new technologies, multimodality, and the arts in ELA, the illuminated text can also be used to support content areas outside of ELA. For example, students could animate historical documents or short reports for any discipline. Illuminated texts encourage students to pay close attention to written texts, to learn with technology, and to make creative choices with artistic tools, so the project’s potential extends beyond ELA classrooms.

The illuminated text is a project my preservice teachers have enjoyed. They have appreciated the freedom to work across modes as they selected music, quotations, and images. Because this multimodal assignment taps into intrinsic motivation, which Amabile (1989) said is essential for encouraging creativity, they tend to do more than satisfy minimum requirements. The assignment challenges them to think beyond the printed page and to envision literature as dynamic, vibrant, and multidimensional. The illuminated text demonstrates that with new technologies come new possibilities for English language arts.

References

Albers, P. (2006). Imagining the possibilities in multimodal curriculum design. English Education, 38(2), 75-101.

Albers, P., & Harste, J.C. (2007). The arts, new literacies, and multimodality. English Education, 40(1), 6-20.

Albers, P., Holbrook, T., & Harste, J. (2010). Talking trade: Literacy researchers as practicing artists. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 54(3), 164-171.

Albers, P., & Sanders, J. (Eds.). (2010). Literacies, the arts, and multimodality. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Alexie, S. (2007). The absolutely true diary of a part time Indian. New York, NY: Little, Brown.

Amabile, T.M. (1989). Growing up creative: Nurturing a lifetime of creativity. New York, NY: Crown Publishers.

Anderson, L.H. (1999). Speak. New York, NY: Penguin.

Beach, R. (2007). Teachingmedialiteracy.com: A web-linked guide to resources and activities. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Beach, R., & Bruce, B.C. (2007). Using digital tools to foster critical inquiry. In D.E. Alvermann (Ed.), Adolescents and literacies in a digital world (pp. 147-163). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Beach, R., & Swiss, T. (2010). Digital literacies, aesthetics, and pedagogies involved in digital video production. In P. Albers & J. Sanders (Eds.), Literacies, the arts, and multimodality (pp. 300-320). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Benson, S. (2008). A restart of what language arts is: Bringing multimodal assignments into secondary language arts. Journal of Advanced Academics, 19(4), 634-674.

Berger, J. (1972). Ways of seeing. New York, NY: Penguin.

Blecher, S., & Burton, G.F. (2010). Saying yes to music: Integrating opera into a literature study. In P. Albers & J. Sanders (Eds.), Literacies, the arts, and multimodality (pp. 44-66). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Boardman, D. (2007). Inside the digital classroom. In T. Newkirk & R. Kent (Eds.), Teaching the neglected “R”: Rethinking writing instruction in secondary classrooms (pp. 162-171). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Bruce, B.C. (2007). Diversity and critical social engagement: How changing technologies enable new modes of literacy in changing circumstances. In D.E. Alvermann (Ed.), Adolescents and literacies in a digital world (pp. 1-18). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Burnaford, G. (with Brown, S., Doherty, J., & McLaughlin, H.J.). (2007). Arts integration frameworks, research, and practice: A literature review. Retrieved from the Eugene Field A+ Elementary website: http://www.eugenefieldaplus.com/academics/A+%20research/artsintegration.pdf

Campbell, K.L. (2011). New technologies and the English classroom. English Leadership Quarterly, 34, 7-10.

Common Core Standards Initiative. (2014). English language arts standards. Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy

Costello, A.M. (2010). Silencing stories: The triumphs and tensions of multimodal teaching and learning in an urban context. In P. Albers & J. Sanders (Eds.), Literacies, the arts, and multimodality (pp. 234-253). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

Deakin, K., & Sindel-Arrington, T. (2010). Illuminating self: Teenagers daring to disturb the traditional book report. Presentation at the Arizona English Teachers Association Conference. Arizona State University: Polytechnic Campus, Mesa AZ.

Deasy, R.J. (Ed.). (2002). Critical links: Learning in the arts and student academic and social development. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED466413)

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. New York, NY: Perigee.

DiVito, M. (2011). Lessons learned from teaching with technology. English Leadership Quarterly, 34(1), 3-5.

Doering, A., Beach. R., & O’Brien, D. (2007). Infusing multimodal tools and digital literacies into an English education program. English Education, 40(1), 41-60.

Eisner, E.W. (2002). The arts and the creation of mind. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Eisner, E.W. (2003). Artistry in education. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 47(3), 373-384.

Flood, J., Heath, S.B., & Lapp, D. (Eds.). (2008). Handbook of research on teaching literacy through the communicative and visual arts (Vol. 2). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Galda, L., & Pellegrini, A.D. (2008). Dramatic play and dramatic activity: Literate language and narrative understanding. In J. Flood, S.B. Heath, & D. Lapp (Eds.), Handbook of research on teaching literacy through the communicative and visual arts (Vol. 2; pp. 455-460). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the imagination: Essays on education, the arts, and social change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Groenke, S.L. (2011). Technology refresh. English Leadership Quarterly, 34(1), 1-2.

Hagood, M.C., Stevens, L.P., & Reinking, D. (2007). What do THEY have to teach US? Talkin’ ‘cross generations! In D.E. Alvermann (Ed.), Adolescents and literacies in a digital world (pp. 68-83). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Haney, W. (2000). The myth of the Texas miracle in education. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 8(41). Retrieved from http://epaa.asu.edu/ojs/article/view/432/828

Harste, J.C. (2010). Multimodality. In P. Albers & J. Sanders (Eds.), Literacies, the arts, and multimodality (pp. 27-43). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Harste, J.C., & Albers, P. (2007). The editorial we: Themed issue on the arts, new literacies, and multimodality. English Education, 40(1), 3-5.

Hicks, T., & Turner, K.H. (2013). No longer a luxury: Digital literacy can’t wait. English Journal, 102(6), 58-65.

Hill, A.E. (2014). Using interdisciplinary, project-based, multimodal activities to facilitate literacy across the content areas. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 57(6), 450-460.

Hinchman, K.A., & Lalik, R. (2007). Imagining literacy teacher education in changing times: Considering the views of adult and adolescent collaborators. In D.E. Alvermann (Ed.), Adolescents and literacies in a digital world (pp. 84-100). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Hirschfeld, N. (2009, October). Teaching cops to see. Smithsonian, 49-54.

Holcomb, S. (2007). State of the arts: Despite mounting evidence of its role in student achievement, arts education is disappearing in the schools that need it most. NEA Today. Retrieved from http://www.nea.org/home/10630.htm

Hughes, J., & Robertson, L. (2010). Transforming practice: Using digital video to engage students. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 10, 20-37. Retrieved from https://citejournal.org/vol10/iss1/languagearts/article2.cfm

Hunter, J.D., & Caraway, H.J. (2014). Urban youth use Twitter to transform learning and engagement. English Journal, 103(4), 76-82.

Isaksen, S.G., & Murdock, M.C. (1993). The emergence of a discipline: Issues and approaches to the study of creativity. In S.G. Isaksen, M.C. Murdock, R.L. Firestien, & D.J. Treffinger (Eds.), Understanding and recognizing creativity: The emergence of a discipline (Vol. 1; pp. 13-47). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

John-Steiner, V. (1997). Notebooks of the mind: Explorations of thinking. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Kajder, S. (2007). Plugging in to twenty-first century writers. In T. Newkirk & R. Kent (Eds.), Teaching the neglected “R”: Rethinking writing instruction in secondary classrooms (pp. 149-161). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

King, J.R., & O’Brien, D.G. (2007). Adolescents’ multiliteracies and their teachers’ needs to know: Toward a digital detente. In D.E. Alvermann (Ed.), Adolescents and literacies in a digital world (pp. 40-50). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Kress, G. (2008). “Literacy” in a multimodal environment of communication. In J. Flood, S.B. Heath, & D. Lapp (Eds.), Handbook of research on teaching literacy through the communicative and visual arts (Vol. 2; pp. 91-100). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading images: The grammar of visual design (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2011). New literacies: Everyday practices and social learning (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Open University Press.

Lapp, D., Flood, J., & Moore, K. (2008). Differentiating visual, communicative, and performative arts instruction in well-managed classrooms. In J. Flood, S.B. Heath, & D. Lapp (Eds.), Handbook of research on teaching literacy through the communicative and visual arts (Vol. 2; pp. 537-542). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Lewis, C., & Finders, M. (2007). Implied adolescents and implied teachers: A generation gap for new times. In D.E. Alvermann (Ed.), Adolescents and literacies in a digital world (pp. 101-113). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

MacArthur, C.A. (2006) The effects of new technologies on writing and writing processes. In C.A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Ed.), Handbook of writing research (pp. 248-262). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

McGill-Franzen, A., & Zeig, J.L. (2008). Drawing to learn: Visual support for developing reading, writing, and concepts for children at risk. In J. Flood, S.B. Heath, & D. Lapp (Eds.), Handbook of research on teaching literacy through the communicative and visual arts (Vol. 2; pp. 399-411). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Miller, L.C. (2007). Space to imagine: Digital storytelling. In T. Newkirk & R. Kent (Eds.), Teaching the neglected “R”: Rethinking writing instruction in secondary classrooms (pp. 172-185). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Miller, S.M. (2007). English teacher learning for new times: Digital video composing as multimodal literacy practice. English Education, 40(1), 61-83.

Miller, S.M. (2010). Toward a multimodal literacy pedagogy: Digital video composing as 21st century literacy. In P. Albers & J. Sanders (Eds.), Literacies, the arts, and multimodality (pp. 254-281). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Miller, S.M. (2013). A research metasynthesis on digital video composing in classrooms: An evidence-based framework toward a pedagogy for embodied learning. Journal of Literacy Research, 45(4), 386-430.

National Council of Teachers of English. (2007). 21st century literacies: A policy brief produced by the National Council of Teachers of English. Retrieved from http://www.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Positions/Chron1107ResearchBrief.pdf

National Council of Teachers of English. (2009). Literacy learning in the 21st century: A policy brief produced by the National Council of Teachers of English. The Council Chronicle, 15-16. Retrieved from http://www.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Magazine/CC0183_Brief_Literacy.pdf

New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60-92.

Nobles, S., Dredger, K., & Gerheart, M.D. (2012). Collaboration beyond the classroom walls: Deepening learning for students, preservice teachers, and professors. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 12(4), 343-354. Retrieved from https://citejournal.org/vol12/iss4/languagearts/article1.cfm

Northrup, T. (2014). Tony Northrup’s DSLR book: How to create stunning digital photography. Waterford, CT: Mason Press.

Ravitch, D. (2010). The death and life of the great American school system: How testing and choice are undermining education. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Rhodes, J.A., & Robnolt, V.J. (2009). Digital literacies in the classroom. In L. Christenbury, R. Bomer, & P. Smagorinsky (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent literacy research (pp. 153-169). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Robbins, B. (2010). Bringing filmmaking into the English language arts classroom. In P. Albers & J. Sanders (Eds.), Literacies, the arts, and multimodality (pp. 282-299). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Robelen, E. (2012, April 2). Arts instruction still widely available, but disparities persist. Education Week’s Blogs. Retrieved from http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/curriculum/2012/04/new_national_data_appears_to.html

Robin, B.R. (2008). The effective uses of digital storytelling as a teaching and learning tool. In J. Flood, S.B. Heath, & D. Lapp (Eds.), Handbook of research on teaching literacy through the communicative and visual arts (Vol. 2; pp. 429-440). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Robinson, K. (2011). Out of our minds: Learning to be creative. Westford, MA: Courier Westford.

Rocco, H. (2011). Publishing student work online. English Leadership Quarterly, 34(1), 6-7.

Ruppert, S.S. (2009). Why schools with arts programs do better at narrowing the achievement gaps. Retrieved from the Arts Education Partnership website: http://www.aep-arts.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/EdWeekCommentary-ArtsEducationEffect.pdf

Sanders, J., & Albers, P. (2010). Multimodal literacies: An introduction. In P. Albers & J. Sanders (Eds.), Literacies, the arts, and multimodality (pp. 1-26). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Sewell, W.C., & Denton, S. (2011). Multimodal literacies in the secondary English classroom. English Journal, 100(5), 61-65.

Sherry, M.B., & Tremmel, R. (2012). English education 2.0: An analysis of websites that contain videos of English teaching. English Education, 45(1), 35-70.

Siegel, M. (2012). New times for multimodality? Confronting the accountability culture. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 55(8), 671-680.

Shoffner, M. (2013). Editorial: Approaching technology in English education from a different perspective. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 13(2), 99-104. Retrieved from https://citejournal.org/vol13/iss2/languagearts/article1.cfm

Swenson, J. (2006). Guest editorial: On technology and English education. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 6(2), 163-173. Retrieved from https://citejournal.org/vol6/iss2/languagearts/article1.cfm

Swenson, J., Rozema, R., Young, C.A., McGrail, E., & Whitin, P. (2005). Beliefs about technology and the preparation of English teachers: Beginning the conversation. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 5(3/4), 210-236. Retrieved from https://citejournal.org/vol5/iss3/languagearts/article1.cfm

Swenson, J., Young, C.A., McGrail, E., Rozema, R., & Whitin, P. (2006). Extending the conversation: New technologies, new literacies, and English education. English Education, 38(4), 351-369.

Young, C.A., & Bush, J. (2004). Teaching the English language arts with technology: A critical approach and pedagogical framework. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 4(1), 1-22. Retrieved from https://citejournal.org/vol4/iss1/languagearts/article1.cfm

Young, J.P., Dillon, D.R., & Moje, E.B. (2007). Shape-shifting portfolios: Millennial youth, literacies, and the game of life. In D.E. Alvermann (Ed.), Adolescents and literacies in a digital world (pp. 114-131). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Zoss, M., Siegesmund, R., & Patisaul, S. J. (2010). Seeing, writing, and drawing the intangible: Teaching with multiple literacies. In P. Albers & J. Sanders (Eds.), Literacies, the arts, and multimodality (pp. 136-156). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Arts and the Common Core Curriculum Mapping Project – http://commoncore.org/maps/resources/art

Arts Education Partnership – http://www.aep-arts.org/

ArtsEdSearch – http://www.aep-arts.org/research-policy/artsedsearch/

Bitstrips – http://www.bitstrips.com/

Capzles – http://www.capzles.com/

Changing Education Through the Arts – http://www.kennedy-center.org/education/ceta/

Commission on Arts and Literacies – http://www.ncte.org/cee/commissions/artsandliteracies

Commission on New Literacies, Technologies and Teacher Education – http://www.ncte.org/cee/commissions/technology

Common Core State Standards – http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/

Edublogs – https://edublogs.org/

Edutopia – http://www.edutopia.org/

English Companion Ning – http://www.englishcompanion.ning.com

Gallery of Teaching and Learning – http://gallery.carnegiefoundation.org/

Glogster – http://www.glogster.com/

Illuminated Text for 1984 – http://vimeo.com/7184543

Illuminated Text for “Cat in the Rain”- https://sites.google.com/site/ghsenglishclasswebsite/home/period-1/-a-cat-in-the-rain-learning-activity

Illuminated Text for Speak (one demonstration slide) – http://yalittech.weebly.com/illuminated-texts.html

Illuminated Text for Wintergirls – http://yalittech.weebly.com/illuminated-texts.html

Lexipedia – http://lexipedia.com/

Make Beliefs Comix – http://www.makebeliefscomix.com/

Moodle – https://moodle.org/

Pinterest – https://www.pinterest.com/

Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education (SITE) Conference – http://site.aace.org/conf/

Song: “I Cut Class” – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3CRgkCIontc

Song: “Soothsayer” – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=adV8-_hgL4g&feature=kp

Storybird – https://storybird.com/

Storyboard That – http://www.storyboardthat.com/

Storyspace – http://www.eastgate.com/storyspace/index.html

Teacher Tube – http://www.teachertube.com/

Teachingmedialiteracy.com – http://www.tc.umn.edu/~rbeach/linksteachingmedia/index.htm

ThingLink – https://www.thinglink.com/

Twitter – https://twitter.com/

Wordle – http://www.wordle.net/

Author Notes

Wendy R. Williams

Arizona State University

Email: [email protected]

How to Make an Illuminated Text