Teacher education programs face the challenge and responsibility of preparing highly qualified, fully certified teachers who are capable of teaching a wide range of literacy skills to an increasingly diverse student population. Although evidence suggests that well designed, traditional teacher preparation programs produce effective teachers, additional new standards and requirements, such as those in the No Child Left Behind Act, limit the amount of classroom time that can be devoted to literacy instruction. With this increase in program requirements for all education certification programs, a method has been needed to extend what is taught in preservice educational classrooms without significantly increasing the credit hour requirements for education certification programs.

One solution to classroom time constraints is to employ innovative instructional delivery systems and modern educational technology to equip preservice teacher educators and their candidates with the skills and knowledge that support the learning of literacy for all students. Online, asynchronously conducted dialog is one alternative that may be effective.

This article describes a mixed methods research study in two preservice undergraduate literacy methods courses. Having previously determined through day-to-day interactions, that undergraduate teacher candidates were not reading their texts nor fully comprehending the theoretical and practical understandings of literacy learning, the professor (the first author) determined that guided small-group discussion was required to achieve these goals. These small groups could grow into communities of learners and explore literacy learning subjects on a deep and meaningful level. However, the professor knew that the allotted class periods did not provide enough time to cover the required material, as well as provide for the small group, in-depth discussions necessary for critical understanding. Therefore, the professor sought out a colleague in the educational technology field (the second author) to see if they could work together to resolve this dilemma.

We decided to approach the small-group discussions using an asynchronous, online discussion board contained in the Blackboard® course management system. Both the students and the professors were familiar with and had used Blackboard in numerous courses. Employing Blackboard ensured that all participants were not overwhelmed with the technological aspects of learning a new program and could, therefore, concentrate on the literacy topic under discussion (Longhurst & Sandage, 2004). By employing online, asynchronous discussions, the selected course evolved into a hybrid, Web-enhanced course. This study investigated and attempted to answer the following research question: How did online prompts and dialog discussion support preservice teacher candidates in defining and refining their understanding of literacy teaching and practice?

Theoretical Framework

Web-enhanced courses, by design, usually involve projects, assignments, discussions, or assessments that take place via the World Wide Web. These Web-enhanced courses, in order to be successful, should be pedagogically based on a constructivist philosophy of learning. Constructivism, in this study, is defined as meaning making (Bruner, 1990) rooted in the context of the situation (Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989), whereby individuals construct their knowledge of, and give meaning to, the external world (Duffy & Jonassen, 1992; Jonassen, Peck & Wilson, 1999; Schunk, 2000). McCombs (2001) referred to these pedagogies as learner centered. In this learner-centered environment, learners construct their knowledge through active participation in the educational process. Learners are “not just responding to stimuli, as in the behavorist rubric, but engaging, grappling, and seeking to make sense of things” (Perkins, 1992, p. 49).

An important aspect of constructivism is collaboration. In asynchronously conducted discussions learners are reviewing, critiquing, and testing each other’s ideas and engaging in collaborative knowledge building (Scardamalia & Bereiter, 1994). Communities of learners and of practice form from these collaborations, especially when learners are working in teams (Brown & Campione, 1990).

Communities of learners, in larger contexts called communities of practice, have been variously defined and described (Brown, 1997; Brown & Campione, 1990; Kearsley, 2000; Lave & Wenger, 1991: Norton & Wiburg, 2003; Palloff & Pratt, 2003, 2007; Wenger, 1998). All of these descriptions have certain commonalities. Learning communities are social cultural organizations. They share values, beliefs, languages, and ways of doing things (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000). Therefore, practices within these communities are characterized by mutual engagement, participation, joint enterprise, shared repertoire, and negotiated meaning (Wenger, 1998).

Educators strive to create such communities in a variety of learning environments. With the advent of modern educational technologies, these environments include not only the traditional face-to-face courses but also Web-enhanced courses, hybrid courses, synchronous distance education courses, and fully online, asynchronous distance education courses. Some of the benefits of a community of learners were listed by Singh (2004):

- The ability to widen the scope of learning by getting multiple experiences and points of view.

- A chance to expand on the structured learning experience by inviting an unstructured dialog with peers and experts.

- A learning buddy or team that helps motivate, validate and reinforce new learning.

- Sharing knowledge in an online learning community (by posting comments in discussion forms, articles, “knowledge nuggets,” or tutorials in a common knowledge base), which establishes your credibility as an expert and promotes your ability to seek mentorship of others when needed.

- Supporting others by asking the right questions and helping others. (p. 79)

Though little research exists for the efficacy of learning communities in online discussions used in traditional face-to-face literacy courses (thereby, making it a Web-enhanced course). An abundance of research has been conducted concerning asynchronous discussions in fully online courses. Distance educators generally have agreed that online discussions were the most critical component of online courses and that the key to successful online discussions was a sense of community among the participants (Alavi & Dufner, 2005; Jonassen et al., 1999; Norton & Wiburg, 2003; Palloff & Pratt, 2001, 2007). Researchers have said that “the key ingredient of an ALN (Asynchronous Learning Network) is the capability for learners to learn anywhere and at anytime and to be part of a community of learners” (Bourne, McMaster, Rieger, & Campbell, 1997). Wegerif (1998) stated, “The first priority should therefore be to build a sense of community…” (p. 46).

The sense of community was noticeably different in these online courses. Lynch (2002) stated that “Web-based courses build a new kind of community that is not bound by location or time. No longer are students relegated to meeting and talking with only those who can stay after class or meet for lunch.”

Within the online learning community discussions, learning takes place and community is built and reinforced (Bourne et al., 1997; Jonassen et al., 1999; Kearsley, 2000; Palloff & Pratt, 2007; Swan & Shea, 2005; Wegerif, 1998). Also, within these learning communities knowledge is generated and built (Bransford et al., 2000). However, community is not automatic; it must be built (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Wenger, 1998). A key ingredient of building community is the notion of legitimate peripheral participation (Lave & Wenger, 1991).

In legitimate peripheral participation, the individual begins to join the community of practice by completing the smaller, less challenging tasks and then moves on to the more challenging tasks. It is a sort of community scaffolding. As individuals move toward competency, they become more contributing and productive members of the community. This process of moving from feeling like a marginal member of the group toward feeling full membership is accomplished online through community discussions.

As Wegerif (1998) wrote, “Individual success or failure on the course depended upon the extent to which students were able to cross a threshold from feeling like outsiders to feeling like insiders” (p. 34). In an entirely online course, this process can take weeks to accomplish. The benefit of a Web-enhanced course is that this scaffolding of community development through legitimate peripheral participation usually takes place in the classroom and may not be a major concern when moving to online discussions.

This present study was also heavily influenced by a socio-psycholinguistic perspective on reading and writing (Goodman, 1973, 1986; Goodman, Watson, & Burke, 1987; Halliday, 1973, 1975; Holdaway, 1979; Phinney, 1988; Rhodes & Dudley-Marling, 1996; Smith, 1986, 1997; Weaver, 2002). This reading theory is guided by the belief that children simultaneously use three language cue systems as they read for meaning: semantic (meaning), syntactic (structure of language) and graphophonic (sound-symbol relationships). The concurrent interaction of these three cuing systems advances the reading comprehension of children.

Overriding these three cuing systems is the pragmatic cuing system, which is used, consciously and unconsciously, to adapt language to fit particular social contexts. Literacy is conceptualized as a complex sociocultural meaning-making process and is viewed as much as a social process as it is a linguistic process. Students were taught to look at miscues as a way to assess readers’ strengths and needs, as well as a window from which to adapt their teaching practices to help readers become more successful.

Background

To answer the research question, we chose an undergraduate literacy course, EDR 344: Language, Literacy, and Linguistic Diversity. This course is the first of two required literacy courses in a teacher preparation program at a midsized northeastern US university. This course is taken in the students’ junior year and includes 25 hours of field experience. EDR 344 is designed to introduce the developing teacher to reading instruction and the development of a reading/writing community. The two sections of EDR 344 included in this study comprised 38 students (32 females, 6 males), all of whom chose to participate in this study.

In EDR 344 the instructor taught the students literacy theory and how it operated in a comprehensive reading program. Additionally, students were instructed in ways to implement a comprehensive approach to reading instruction that implemented semantic, syntactic, graphophonic, and pragmatic sources of information; a print rich environment with authentic reading materials at the appropriate instructional level; and the latest research about literacy development and its relationship to classroom instruction for all learners. EDR 344 was also designed to assist education majors in developing a set of clear principles and strategies for literacy instruction.

An integral part of EDR 344 was its use of video case studies. The use of video case studies has been supported by considerable research in the ways technology and video-based cases might be used in literacy teacher preparation (Ferdig, Roehler, & Pearson, 2002; Kinzer & Risko, 1998; Teal, Leu, Labbo, & Kinzer 2002).

The video-cases used in EDR 344 were part of a larger National Science Foundation (NSF) research project entitled Case Technologies to Enhance Literacy Learning (CTELL), with principal investigators from four major universities. (Alhough the students in these two preservice undergraduate literacy methods courses were also participants in this larger NSF study, the current research in online dialog was in no way connected to the NSF study.) CTELL uses multimedia, anchored case-based studies delivered over the Internet to effectively train preservice teachers to understand and implement principles of effective literacy instruction.

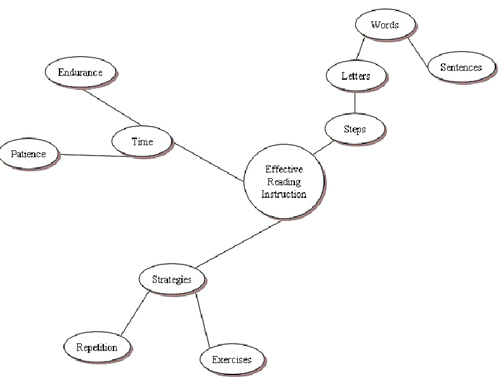

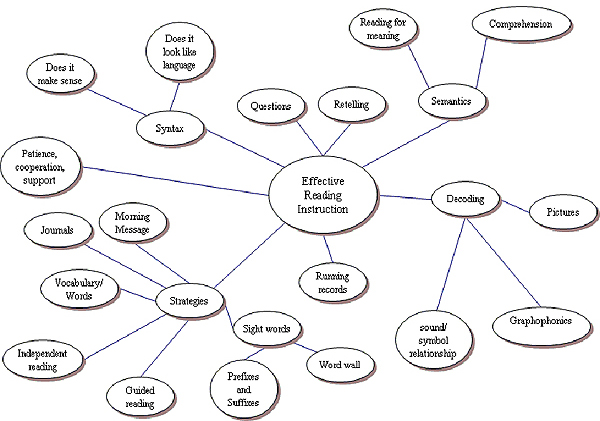

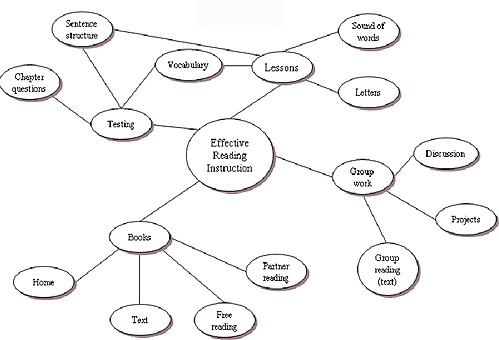

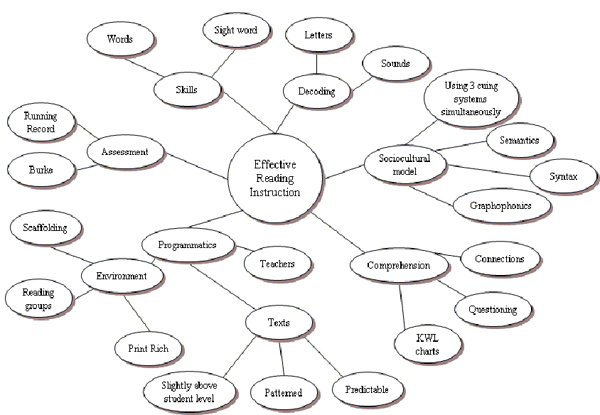

In the CTELL project students viewed video cases, downloaded from the Internet, of actual K through third-grade classroom teachers, who practiced the craft of literacy teaching. As a requirement, CTELL participants had to complete both a pre- and postassessment consisting of a “concept web” or semantic web for effective reading instruction. Directions to students given in a course handout were as follows: “Concept Webs (also known as semantic maps or semantic webs) are diagrams that show how a key idea is related to associated concepts (e.g., attributes, examples) that have been arranged in categorical clusters.”

Students were provided with two concept map examples. These example concept maps were deliberately selected to have nothing to do with reading, so that these examples did not lead students but merely served as a guide to constructing their own concept maps. Students had 10 minutes to draw the map. They were then instructed to select three key aspects of effective reading instruction and write a short paragraph explaining how they would address each in a third-grade classroom. The data from these assessments were used to measure a change in participants’ literacy understanding. Examples of both the pre- and postassessment concept maps are found in Appendix A.

Method

One requirement for this course was that students had to participate in online group discussions conducted on Blackboard. In the “Communications” area of Blackboard, in the “Group Pages” section, there is an area where private, small group discussions may be held. We set up the EDR 344 Blackboard to accommodate nine small group discussion areas. Each of these nine small group discussion boards was private and was restricted to the instructor and the students who were assigned to that discussion group. The other students could not see or participate in any of the small group discussions other than their own. These private, asynchronous discussion areas were available to participants (instructors and students) around the clock, 7 days a week.

Group Make-Up

Each of the nine individual discussion groups was composed of four to five students. Brewer and Klein (2005) pointed out that the use of small group methods in asynchronous online discussions helps to reduce anonymity and isolation and that online groups “corroborate the findings for face-to-face small group work” (p. 334). As an added benefit, because this was a Web-enhanced course, many of the pitfalls associated with small discussion groups in completely online asynchronous courses were avoided (Brewer & Klein, 2005). Each group had members that represented each of the different education majors offered at the university: early childhood, elementary, and special education/elementary. By combining students from differing education majors the participants were more likely to see literacy from various perspectives, as well as come to understand socio-psycholinguistic literacy theory.

Online Discussion

Asynchronous online discussions were conducted throughout the 14-week semester. To begin the discussions and provide a guiding topic, the instructor posted a total of five prompts (see Appendix B) over the course of the semester. The instructor told the students that to successfully participate in the online dialog all assigned material must be read prior to the posting of each prompt. In this way students were encouraged to take responsibility for their own learning. Directions contained in the course syllabus for the online discussions emphasized the following:

- Each student was responsible for making 7-10 postings per prompt.

- Each of these postings was to be substantiative. Substantiative entries were defined as those that made detailed, extensive, and valid references to the text, class lectures, and practice in the field.

- A total of 25 points were given for online discussions, one quarter of their overall grade. Participants were scored individually on their respective contributions to the discussion.

Four roles were performed by the individual members of each group: facilitator and discussion leader, summarizer, connector, and illustrator (as in Daniels, 2001). Recent research by Brewer and Klein (2005) supports the use of roles in small group, online, asynchronous discussions. Each of the four roles rotated among group members, with each member serving in each role at least once, but no more than twice. Once the instructor posted the guiding prompt, each group then had 10-14 days to respond to this prompt. Individual members were responsible for responding to the posted prompt and were also expected to respond to and interact with each other throughout the online discussion. These personal interactions were expected to enhance participant interest, engagement, and motivation (Bourne et al., 1997; Kearsley, 2000; Palloff & Pratt, 2001, 2003, 2007; Wegerif, 1998). The responsibilities for each of the four roles in the discussion groups were as follows:

- The facilitator of the group kept the discussion flowing and posed additional questions if the dialog needed a boost. The facilitator also emailed any students who were not contributing to the group online discussion to encourage them to be more active participants in their online learning community.

- The connector tied what was being discussed online to field experience, course texts, class discussions, and life experiences.

- The summarizer set the cut off time for the online dialog and sent a final email reminder 24 hours before the prompt was about to close. The summarizer cut and pasted the online dialog, concisely summarized the gist of the discussion, and emailed the summary to all group members with a specific email to the illustrator.

- The illustrator was responsible for illustrating the concise summary through drawing, collage, computer generated figures, pen and ink, etc. The illustration decisions were left up to the specific illustrator and not the group members.

At the end of this process the summarizer and illustrator provided the instructor with all of the artifacts resulting from each online discussion.

Prompts

Appendix B is a list of the online prompts used in EDR 344. The prompts illustrate that the course was taught from a socio-psycholinguistic perspective of literacy learning. The instructor posted prompts sequentially, with each prompt being available online for approximately 2 weeks. The course texts (Cole, 2004; Orwocki, 2003) and articles used in support of these texts provided the basis for these prompts.

Grading

Online discussion comprised 25% of the final grade for each student. Each student was graded individually, not on a collaborative basis and was scored on the following criteria:

- Met the minimum number of postings required and their postings were evenly spread throughout the discussion (so that they did not front-end their posting or lurk and join the discussion after it was well underway).

- The substantiative quality of the postings (text reference, lecture reference, and synthesis to critical understanding of literacy concept).

- How well the postings stayed focused on the topic.

- How well the postings elaborated and enhanced the overall discussion.

- Whether they supported their arguments with authoritative citations.

Data Collection

For one portion of the CTELL pre- and postassessment, students had to construct “concept webs” of effective reading instruction. (Examples of both the pre- and postassessment concept maps are found in Appendix A.) Once the students completed the web component, they then explained three key aspects from their concept web and in a short paragraph, for each aspect, explicated how they would address each of these in a third-grade classroom. We do not know how CTELL used this assessment data. However, we used this data to determine growth and development of the participants’ literacy understanding over time.

Additional data were collected on all 38 preservice educators and consisted primarily of all online dialog group discussions, their summaries, and the accompanying illustrations. In addition, a postsurvey was developed and administered to the participants regarding their impressions of the online dialog. Thirty-five of 38 students returned the postsurvey, for a return rate of 92%.

Qualitative data collection and analysis were ongoing. Employing a constant comparative method of analysis, we searched each student’s pre and post concept web for prominent themes and emerging patterns. In this “open coding” (Strauss, 1987) stage, each data source was read at least twice to gain an overall impression and then reduced to meaningful units (phrases, terms). Once specific units emerged that were either explicitly stated or implied in the concept webs, these units were listed. This preliminary data was then transferred to coding sheets. Each identified category or pattern was analyzed and confirmed or disconfirmed through close examination of all of the concept webs.

The initial data set was reread three different times to confirm or disconfirm the evidence of the preliminary identified patterns. The initial patterns were then enriched, expanded, contracted, or collapsed. Through this “axial coding” process (Strauss, 1987) we were able to better refine the categories. Finally, we looked across all students’ data to identify the recurring patterns and themes. (Categories were considered major if at least 18-20 students made reference to the terms that described preservice teachers’ interpretations of effective reading instruction for third grade.) Three major categories ultimately emerged as the most common patterns in the predata set: Communication, Language, and General Education or Reading Terms. In the postdata set, five categories ultimately emerged as the most common patterns: Reading Theory, Assessment, Reading Formats, Reading Strategies, and Classroom Environment.

Findings

Findings indicate that online small group discussion deepened and broadened preservice teachers’ literacy understanding. The online dialog enabled the 38 undergraduates to work together in learning communities to make connections between their own personal experiences, readings, lectures, assumptions, and their theoretical understanding of literacy learning, and apply and transfer this knowledge to their own literacy practice. This collaboration reinforced literacy concepts covered in class and course texts. The online discussions also obligated preservice undergraduates to read class texts more closely and meaningfully.

Preservice teachers’ literacy learning benefited from their engagement and collaboration with each other. The online collaborative learning environment developed a richer base of literacy learning knowledge for the preservice teachers (as also reported in Pallof & Pratt, 2007). Providing many opportunities for supportive and interactive online dialog enabled the preservice teachers to analyze, negotiate, and reflect on what they and their classmates said about literacy learning (as also reported in Wenger, 2007). This ongoing and continuous collaboration resulted in a supportive community of learners (Brown , 1997). Clearly, students’ knowledge and understanding of literacy grew as a result of their course readings and work in the class; however, the synergistic effect of these learning communities enabled the participants to be more confident and knowledgeable in the application of their literacy understanding and practice (as reported in Bransford et al., 2000).

Participants were able to try out their own literacy understandings and thinking and receive positive and supportive critique from their group members (as also reported in Bransford et al., 2000: Wenger, 1998). This feedback generally reinforced or expanded what the individuals said. At other times the feedback offered positive correction, and the learning community could inform the individual’s thinking in order to refine the individual’s understanding. For example, one student made the comment that phonics is the most integral part of reading. Students in her group immediately challenged her stance, stating that phonics was but one cuing system in a pallet of cuing systems. After much discussion the student changed her position to agree that all readers should be taught multiple cuing systems and learn to use them simultaneously (as recommended by Wenger, 1998).

Trying to share an online dialog session in an article is difficult. The online dialog sessions were extensive. Each student’s entry could be three to four paragraphs or longer, and each student usually responded 7 to 10 times for a prompt. When the online sessions were cut and pasted into a printout for this research, the entire prompt responses would usually run 10 to 15 single-spaced pages. The example excerpt in Appendix C has been condensed for brevity. This online dialog was a response to Prompt 4 on comprehension.

Through the active thinking and the give and take of online dialog sessions, students developed a much richer theoretical knowledge of reading. Students were compelled to read the texts for the course so that they could participate knowledgeably in online dialog. This learning community was emotionally safe and fostered rich online dialog.

By combining their own personal experiences, their experiences with children in the field, and the course lectures and course readings, students created their own written interpretations and safely tried out their thinking with their own community of learners. Through this process of active engagement, reviewing, questioning, problem solving, and clarifying each others’ written thinking, each small learning community collaborated to create a much richer and more knowledgeable understanding of reading theory and practice.

Pre-Assessment Data

The individual students’ initial concept webs for effective reading instruction and their explanations of the three key concepts for teaching reading in a third grade classroom were coded to illuminate the categorical patterns using the students’ own terms. Initially, the students used general terms to describe what they perceived to be literacy. The pre-assessment data broke down into three broad categories, as seen in the Table 1.

Table 1

Pre-Assessment Student Key Concepts

Communication | Language | General Educational or Reading Terms |

Voice | Language | Books |

Communication. The students’ understanding of the teaching of literacy before the start of the class was limited and unfocused. Many students wrote about what we categorized as communication. There was considerable focus on having patience and being able to speak clearly, neither of which have a great deal to do with the teaching of literacy:

Communication to me is by far the most effective reading instruction. For one, it all depends on how the instruction is delivered to these kids. If it is delivered in a manner they can’t understand then they will be lost.

You will need a loud, clear voice to first get the attention of the class and then read and explain the directions or to help a child understand what they are reading. If you are reading you cannot be mumbling.

I would make sure when giving directions to a third grade class that I give each direction in the order they are to do them in…I would want to be sure the directions were in the order to be done in because kids at that age will usually just do the first thing they are told.

Being clear as a teacher and being able to communicate with young learners is part of effective classroom practice. Most likely, students addressed the importance of clear communication because they were so unsure of what constituted effective literacy practice. Students were provided 10 minutes to draw a concept map and an additional 10 minutes to write about three concepts. It seemed that students felt compelled to use that time to write about how they thought teachers should communicate with children rather than about literacy. Students were mystified by the complex process of literacy and seemed to think that communication in and of itself was a good instructional literacy procedure. Students were familiar with how to communicate and, therefore, more comfortable in writing about it.

Language. Students also saw language as important to beginning reading instruction. We categorized the labels and vocabulary of grammar and phonics under language. One student stated,

The first topic I would address in a third grade class is language. Students must understand what language is before you can break it down any further for them. I would teach them this by showing them other languages and teaching them the value of language in a society.

Many students also realized the importance of sounds in beginning reading:

Learning the correct sounds and pronunciation of each word is very important. Students have to know whether a vowel is long or short and what a word sounds like when two or more consonants are put together.

I think phonixs [sic] is important because it helps children learn how to sound out words they may not know. It teaches them important tools to read and spell.

Students listed terms that they knew were important to reading, but they did not seem to know exactly how those terms might be important. Students seemed to think that language labels (grammar, sentence structure, sounds, phrasing, and vocabulary) had something to do with the teaching of reading.

General Education or Reading Terms. The final category was filled with labeling of general education and reading terms. Students seemed to list fairly generic terms (books, steps, class work) without any concrete evidence of understanding what the “reading techniques” or “materials” would be in the teaching of reading. As a further example of this limited and unfocused understanding of literacy, many students saw the selection of appropriate texts as important but never defined exactly what constituted appropriate. In class, students would learn that appropriate texts are those that fall within a reader’s Zone of Proximal Development, slightly above what they can do for themselves.

Several students also mentioned the amount of time spent reading, for example,

Teaching third graders to read I imagine will be an extremely repetitive and time consuming adventure. Time is the first key aspect I believe because without time nothing gets done and with time comes patience. I think 20-30 minutes a day would be sufficient in teaching third graders to read

The length of the reading session a third grader has is very important to his or her actual reading… A certain amount of time should be set aside to read.

As many researchers document the need to provide extended periods of time for the improvement of literacy, these undergraduates saw about 30 minutes a day as all one would need to teach reading effectively.

In sum, students were unsure of what constituted the teaching of reading in a third-grade classroom. The majority listed a group of terms that they did not define. Others listed terms like phonics or vowels and were not sure what these terms’ specific roles would be in the teaching of reading. A surprising number of students addressed the need for a “loud, clear, understandable speaking voice,” and for giving clear directions. Communication, Language, and General Education or Reading Terms were three categories that demonstrated students’ generic understandings and confusions about teaching reading in a third grade classroom. Students focused on narrow subtasks of the reading process (phonics and grammar) that are only components of a complete theory of reading.

Postassessment Data

The individual students’ postassessment concept webs for effective reading instruction and explanations of the three key concepts for teaching reading in a third-grade classroom were again coded to reveal the patterns in the students’ terms. Unlike the pre-assessment data, the postdata were specific, concrete, and detailed. The post-assessment data broke down into five specific categories as seen in Table 2.

Table 2

Postassessment Student Key Concepts

Reading Theory | Assessment | Reading Formats | Reading Strategies | Classroom Environment |

| 3 cue systems simultaneously: semantics, syntax, and graphophonics Scaffolding Cross checking Zone of proximal development Vygotsky Reading for Meaning Phonemic Awareness Phonics | Reading Interviews Running Records Retellings | Guided Reading Independent Reading Silent Reading Oral Reading Teacher modeling Whole group instruction Scaffolding | Blanking Book Walks Directed Reading Thinking Activity Comprehension Strategies: Predicting, questioning, retelling, summarizing, inferencing, establishing prior knowledge, schema K-W-L Thematic webs Graphic Organizers | Print Rich Environment\ Pragmatics |

Reading Theory. Most students discussed reading theory knowledgeably and focused specifically on the importance of making readers consciously aware of all three cuing systems: graphophonics, semantics, and syntax. Matt wrote,

Semantics, syntax and graphophonics are the key aspects of effective reading instruction. Reading is a process. Semantics, or reading for meaning and comprehension, is very important because it enables the reader to understand what they are reading. Graphophonics, or sound/symbol relationships, enable the learner to use the sounds in the words to read effectively. Syntax, or knowledge of language, is also an important part of the reading process because language is what you are striving for and not nonsense. Using these three cue systems simultaneously answer the vital questions, “Does it make sense? Does it sound like language?” and “Does it begin with that sound?” These three aspects put together working simultaneously make up the reading process.

Repeatedly, students used the terms of reading theory correctly and defined them specifically and with good insight. Rather than merely listing terms and providing generic definitions, as was done in the pre-assessment, students were able to explain and demonstrate their understanding of reading theory.

Assessment. Most students recognized the important role that assessment played in planning for teacher instruction. Students also understood how assessment informs and modifies next steps instruction.

In a third grade classroom I would monitor the students’ reading progress using reading interviews and running records. The initial interview will give me an idea of what the student already knows to do when reading (cues used) and how they feel about themselves as a reader. The final follow up interview will show me if the student learned any important strategies to use when they don’t know a word or when reading didn’t make sense. I would use running records periodically to see if there is any progress with the student’s reading and to assess if the books they are reading are on an instructional level or not. (Tara)

It is important to know and understand what level a reader is on through the use of running records or the DRA (Developmental Reading Assessment). The student will indicate to the teacher what his/her strengths and weaknesses are. This would therefore allow the teacher to plan teaching effective reading strategies. (Tori)

Students were able to discuss assessment in concrete terms and also indicated that assessment was used to inform instruction. In the pre-assessment a few students mentioned testing, but not a single student defined it. This seemed surprising in the light of the requirements of the No Child Left Behind Act.

Reading Formats. Many students commented on the structure and format of guided reading, silent reading, and independent reading, as well as their roles as the teacher in these formats. Michael wrote,

Guided reading is a format that enables the teacher to work with a small group of children – usually no more than six. The children should all be reading at about the same level. The teacher should preselect a book for the children to read making sure that it is “just” beyond their ability. You want to make sure that there are places where the child would need to apply a strategy. The teacher should begin the lesson with teaching a particular strategy like blanking or visualization. Then he should show the children how the strategy works. The children should then read their books and practice the strategy. At the end the entire group should discuss how things went and how the strategy worked and helped. This should all happen in about 25 minutes.

This example was just one showing a student’s concrete understanding of what should happen instructionally during guided reading. Many students wrote about guided reading in specific detail, not only discussing the format, but more importantly, their role as teachers. Students were also able to describe workshop classrooms and the role of silent reading in the literacy classroom.

Reading Strategies. All students included specific reading strategies on their concept webs: blanking, DRTA (Directed Reading Thinking Activity), questioning, and so forth. In addition, they discussed the process of specifically teaching particular strategies to beginning readers and providing time for readers to practice the strategies. Many students spoke of the importance of teacher scaffolding. Katie wrote that the teacher’s important role was to make sure that students had

reading behaviors of scaffolding, cross checking and automatically applying reading strategies. I will assess my readers at the beginning of the year to check how well they use their strategies. All of my students will learn to crosscheck/recognize when they are having difficulty with reading, they need to have a strategy(ies) to use when coming to a word/problem in reading. I need to scaffold by modeling how to cross check and use miscue strategies. This will be a continued focus/emphasis/assessment throughout my entire year.

Students repeatedly wrote about specific strategies and the importance of teacher scaffolding. They recognized that learning to read is a process, and with teacher guidance and support it could become an enjoyable process for both the child and the teacher.

Reading Environment. Most students focused on creating a supportive, sensitive reading environment in their respective classrooms. Students recognized the role of pragmatics in fostering proficient readers. The following three excepts demonstrate this understanding.

I would focus on the student – classroom relationship, the student – teacher relationship, and the student – book relationship. I would make sure all 3 of these relationships lead to a positive learning environment for the student. (Debbie)

Included in the environment is the atmosphere created by the teacher. An encouraging style that focuses on good instruction followed by a “workshop” actually working. Students are encouraged to guess, try, and make errors without consequences. The teacher should also convey her love of reading, explaining the joys of being involved in a good book. (Janey)

Pragmatics is what makes or breaks a classroom. It’s the environment that’s established when the children enter the classroom. The environment should be reading rich so that it encourages children to read. The teacher should be doing a great deal of modeling and scaffolding to point students in the right direction of how to engage in literacy. (Chelsie)

Students demonstrated their understanding of how teachers established learning communities in their classrooms. Students were able to discuss the importance of teacher demonstrations and providing a reading rich environment. These statements were very different than the pre-assessment statements, in which students discussed the teacher’s voice and enunciation.

In sum, preservice teachers’ literacy learning benefited from their active engagement and collaboration with each other in online learning communities. The preassessment data were filled with generic terms and listings that demonstrated little or no understanding of teaching reading in a third-grade classroom. The post assessment data concretely demonstrated students’ specific understanding of what teachers did or needed to do in order to teach reading successfully in a third-grade classroom. Students showed not only their relevant knowledge base about reading theory but also how that understanding of theory was implemented in classroom practice.

Final Survey

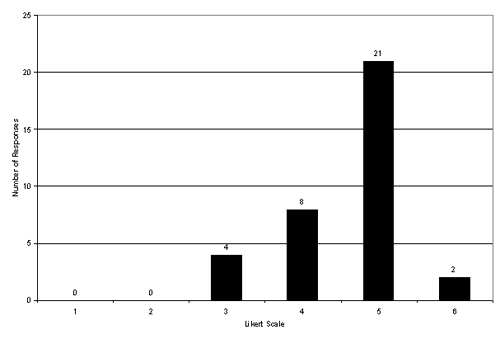

The final survey (see Appendix D) was anonymous and was to be returned by slipping the surveys under the instructor’s door. Surveys were only used to determine student impressions of online dialog and its usefulness in their learning experiences. The narratives indicated the students’ beliefs about the efficacy of this technological tool in furthering their understanding of literacy learning. The final survey gave students the opportunity to report on how they felt about the online discussions. For example, the first question was a Likert scale and asked students, “How helpful was the online discussion in aiding you in your understanding of literacy learning?” Thirty-five of 38 students returned the survey. Figure 5 presents the results of Question 1 as to the overall helpfulness of the online discussion. The majority of the students (66%) thought the online dialog was very helpful.

Figure 1. Results of final survey of perceived usefulness of online discussions (Question 1).

The second question and all subsequent questions on the survey were open-ended questions. These questions could be answered in either a positive or negative manner. The second question on the survey asked, “What were the strengths of the online discussion group in furthering your understanding of literacy learning?” Many students stated that the online discussion “forced” them to do the class reading assignments with “deeper understanding” and enabled them to “process it through the postings.” Most students liked the idea of learning from each other and seeing different perspectives, “Hearing other peoples’ points of views and how they comprehended readings was very helpful” and enabled them to “see the topic in a different way than what I had originally seen it.”

Most students commented on liking the ability to discuss the topic on “their own times and schedules,” and how the dialog made it “easier” and “reinforced” and “furthered” their understanding by helping “to highlight important strategies and concepts from the chapters in our book.” One student commented on how the dialog helped the concepts to “stick in your mind better because not only are you just talking about it in class, but you are also thinking about it at home.”

Question 3 asked, “How did the online discussion help in furthering your understanding of literacy learning?” Almost every single student addressed the fact that they had to read the text more deeply, understand it, and then communicate with their group members about literacy concepts, making it “easier to process the information read and the information learned in class.” Most students discussed how the group helped to clarify any misunderstandings and that they were able “to see what other members thought of the subject under discussion. This would help me better understand the issue from other points of view.” This shared experience “gave me a chance to reflect on other’s ideas and experiences.” Repeatedly students made comments similar to the following: “It allowed me to have a better understanding of all the topics,” and “It allowed us to think for ourselves without sitting in class simply being lectured.”

Question 4 asked for the strengths that the student brought to the discussion. As an example, one student stated that they “added in real-life experiences and key information from class and the text.” Other students said that they “added in my points about what I thought,” “added some differing views that were helpful,” “I seemed to bring up good points that no one in my group thought of and then they agreed.” Several stated that they “helped to keep the discussion going.” Most of the comments centered on individual contributions in knowledge and personal experiences. One participant stated: “I guess that we each brought our own different opinions and thoughts that corresponded to how we all grasped the readings.”

Leadership was mentioned by a couple of students:

I felt I brought, for the most part, a clear understanding to the questions being asked in the prompts. I always tend to go back and bring up what we’ve gotten so far, as to not repeat and move forward in our discussion.

Another stated, “I was a leader in stating new ideas/concepts and elaborating on other ideas.” One participant brought “comic relief” to the discussions.

Question 5 asked for what specifically the students would incorporate in their student teaching. Students reported, “I learned a lot about techniques for fostering comprehension and concepts of scaffolding,” “Discussion about the strategies helped me better understand many, and a better idea of when and how to use them,” and “I learned a lot of ways that teachers can teach young children to comprehend what they are reading that I had no idea about.” They also listed and defined the many reading strategies they would directly teach and implement. Specifically mentioned were visualization, predicting, and summarizing.

Question 6 asked, “In all honesty did the online discussion help you with your knowledge of literacy learning?” Thirty-four of the students answered “yes.” Students stated, “With learning about literacy in class and then having additional discussions about it within our groups helped me to better understand,” and it “made it a constant thing, definitely good.” Students talked about how the discussion “helped clarify information that I read in the text. We explained it to each other and provided each other with examples.” One student wrote that, “Discussion prompted me to actually think about the concepts and think about them much further than I would have otherwise.” Students felt that online discussion provided another way of learning the material “besides taking notes or just reading the text.” Only a single student did not see it as beneficial: “No they were fillers for fairly simple concepts.”

Question 7 asked, “In all honesty, did you like the online discussion? If so, why? If not, why not?” Twenty-nine students answered “yes,” that they liked the online discussion; four answered “yes and no”; and two students answered “no.” Most students reported that it was not a stressful assignment and helped them understand literacy concepts: “You were able to argue or agree and discuss different viewpoints,” as well as provided “added support from other group members.” One student was “a shy person” and was able to get “my point across more when I was able to type or write.” Another student stated that, “it was a way to learn about new ways of thinking about different topics and it helped me bring my thoughts together.”

Clearly, the participants liked the process of trying out their thinking and understanding in this safe and supportive learning community (as consistent with the findings of Kearsley, 2000; Swan & Shea, 2005; Wegerif, 1998). Students also perceived as helpful the sharing of each others’ ideas with the group. This sharing helped to clarify and extend the group’s literacy knowledge (as in Lave & Wenger, 1991, Wenger, 1998). For example, “The discussion allowed for different viewpoints that may not have been said in class.” One student summed up dialog discussion by stating,

Yes, because it forced four people to talk about topics like guided reading and compare different thoughts. I can’t tell you how many times my group members have changed my view points as well as me changing theirs. This definitely helped us master the material.

Discussion

This study provides insight into how a specific use of an instructional delivery system and use of asynchronous discussion technology equipped preservice educators with enhanced skills and knowledge that supported the learning of literacy for all students, an area that had not been previously addressed. We found support for the research conducted prior to the study. Though none of the prior research dealt specifically with literacy learning using online discussions as an adjunct to a face-to-face environment, the prior research was confirmed in the areas of online discussions, community building, the synergistic effect of group discussion, and the increased knowledge of the participants.

It further details how a specific pedagogical approach supported preservice teacher candidates in understanding literacy concepts and how to teach literacy. Online dialog helped to bridge the gap between key literacy ideas and instructional practice. The research findings point to the potential benefits of online dialog in enhancing professional teacher preparation in literacy. Using a constructivist methodology and philosophy, we created learner-centered environments (McCombs, 2001). In these learner-centered environments the preservice teacher candidates constructed their knowledge through active participation in their own educational process and the educational processes of their peers (as in Schunk, 2000). As the online small group community of learners developed over time, the students’ supporting and trusting attitudes toward each other and the way they interacted shaped the depth of the dialog.

Specifically, this study supported the notion that asynchronously conducted discussions, even in face-to-face courses, support students in acquiring and refining their content and pedagogical knowledge needed to teach literacy. These learners were engaging, grappling, and seeking to make sense of these things (as also found in Perkins, 1992). These preservice teachers engaged in Web-based asynchronous discussions where they reviewed, critiqued, tested each other’s ideas, and engaged in collaborative knowledge building (Scardamalia & Bereiter, 1994). The asynchronously conducted discussions scaffolded and supported undergraduates in learning communities (Bransford et al., 2000; Brown & Campione, 1990) in order to articulate and refine their literacy understanding.

This study has implications for how teacher educators prepare teacher candidates in the teaching of literacy for all learners. Teacher educators need to provide prompts and “think time” in online discussion that encourage teacher candidates to consider how teachers teach all learners and to make the connections between theory and practice.

Online discussions provide opportunities for students to engage in thoughtful consideration of theory and practice that enables them to question, clarify, refine, develop and extend their own, and each other’s, knowledge and skills in support of literacy learning. This type of collective knowledge building in a community of learners acts synergistically as a scaffold enabling the participants to develop a more concrete and deeper level of literacy understanding (Brown & Campione, 1990).

Online discussion supports teacher candidates as they develop the knowledge and skills needed to enhance literacy development in diverse learners. The present study demonstrated the need for teacher educators to provide opportunities for meaningful collaboration over time. It also provided opportunities for students to be engaged and responsible for their own learning, thereby supporting them in making more pedagogical connections enhancing future teaching practice.

Our research suggests that the negotiated and collaborative knowledge building of online discussion offers a potentially productive route to enhance professional teacher preparation in literacy. Providing multiple and rich experiences for discussion in supportive learning communities promotes a deeper and more tangible and concrete understanding of literacy.

In sum, the learning communities in this study used the online discussion to build collaborative knowledge of literacy, share multiple experiences and informed views of literacy, learn the language of literacy theory, and validate every individual’s understanding of literacy. These outcomes were accomplished both in the classroom and the online discussions. The added online discussion increased the students’ understanding of literacy instruction, an assertion validated by student feedback and comments. Overall, individual participants increased their own learning while nudging others to think differently about literacy and how to teach it. The practice of online discussion in EDR 344 proved so effective that it will be adopted for all future courses.

References

Alavi, M., & Dufner, D. (2005). Technology-mediated collaborative learning: A research perspective. In S. R. Hiltz & R Goldman (Eds.), Learning together online: Research on asynchronous learning networks (pp. 191-213).Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Bourne, J. R., McMaster, E., Rieger, J., & Campbell, J. O. (1997). Paradigms for on-line learning: A case study in the design and implementation of an asynchronous learning networks (ALN) course. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 1(2), 38-56.

Bransford, D., Brown, A., & Cocking, R. (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience and school. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Brewer, S., & Klein, J. D. (2005). Type of positive interdependence and affiliation motive in an asynchronous, collaborative learning environment. Educational Technology Research & Development, 54(4), 331-354.

Brown, A. L. (1997). Transforming schools into communities of thinking and learning about serious matters. American Psychologist, 52(4), 399-413.

Brown, A. L., & Campione, J. C. (1990). Communities of learning and thinking, or a context by any other name. In D. Kuhn (Ed.), Contributions to human development: Vol. 21. Developmental perspectives on teaching and learning thinking skills. (pp. 108-126). Basel, Switzerland: Karger.

Brown, J.S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18, 32-42.

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cole, A.D. (2004). When reading begins: The teacher’s role in decoding, comprehension, and fluency. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Daniels, H. (2001). Literature circles: Voice and choice in book clubs and reading groups. York, ME: Stenhouse Publishers.

Duffy, T. M., & Jonassen, D. H. (1992). Constructivism and the technology of instruction: A conversation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Ferdig, R.E., Roehler, L.R., & Pearson, D.P. (2002) Scaffolding preservice teacher learning through Web-based discussion forums: An examination of online conversations in the Reading Classroom Explorer. Journal of Computing in Teaching Education, 18(3), 87-94.

Goodman, K. (1973). Theoretically based studies of patterns of miscues in oral reading performance. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED079708)

Goodman, K. (1986). What’s whole in whole language? Richard Hill, ON: Scholastic.

Goodman, Y., Watson, D., & Burke, C. (1987). Reading miscue inventory: Alternative procedures. Katonah, NY: Richard C. Owens.

Halliday, M.A.K. (1973). Explorations in the functions of language. New York: Elsevier North-Holland.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1975). Learning how to mean: Explorations in the development of language. London: Elsevier.

Holdaway, D. (1979). The foundations of literacy. Sydney, Australia: Ashton Scholastic.

Jonassen, D. H., Peck, K. L., & Wilson, B. G. (1999). Learning with technology: A constructivist perspective. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill.

Kearsley, G. (2000). Online education: Learning and teaching in cyberspace. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Kinzer, C.K., & Risko, V.J. (1998). Multimedia and enhanced learning: Transforming preservice education. In D. Reinking, M.C. McKenna, L.D. Labbo, & R.D. Kieffer (Eds.), Handbook of literacy and technology: Transformations in a post-typographic world (pp. 185-201). Mawah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Longhurst, J., & Sandage, S.A. (2004). Appropriate technology and journal writing: Structured dialogs that enhance learning. College Education, 52(2), 69-75.

Lynch, M. M. (2002). The online educator: A guide to creating the virtual classroom. New York: Routledge.

McCombs, B. L. (2001). What do we know about learners and learning? The learner-centered framework: Bringing the educational system into balance. Educational Horizons, 79(4), 182-193.

Norton, P., & Wiburg, K. M. (2003). Teaching with technology: Designing opportunities to learn (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Orwocki, G. (2003) Comprehension: Strategic instruction for K-3 children. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2001). Lessons from the cyberspace classroom: The realities of online teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2003). The virtual student: A profile and guide to working with online learners. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2007). Building online learning communities: Effective strategies for the virtual classroom. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Perkins, D. N. (1992). Technology meets constructivism: Do they make a marriage? In T. M. Duffy & D. J. Jonassen (Eds.), Constructivism and the technology of instruction: A conversation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers

Phinney, M. (1988). Reading with the troubled reader. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Rhodes, L., & Dudley-Marling, C. (1996). Readers and writers with a difference: A holistic approach to teaching struggling readers and writers (2nd ed). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (1994). Computer support for knowledge-building communities. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 3(3), 265-283.

Schunk, D. H. (2000). Learning theories: An educational perspective (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Singh, H.. (2004). Succeeding in an asynchronous environment. In G. M. Piskurich (Ed.), Getting the most from online learning. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Smith, F. (1986). Understanding reading. (3rd ed). Hillsdale, NH: Erlbaum.

Smith, F. (1997). Reading without nonsense. (3rd ed). New York: Teachers College Press.

Snow, C., Burns, M., & Griffin, P. (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young children. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Strauss, A. (1987). Quantitative analysis for social scientists. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Swan, K., & Shea, P. (2005). The development of virtual learning communities. In S. R. Hiltz & R. Goldman (Eds.). Learning together online: Research on asynchronous learning networks (pp. 239-260). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Teale, W., Leu, D., Labbo, L., & Kinzer, C. (2002). The CTELL project: New ways technology can help educate tomorrows reading teachers. The Reading Teacher, 55(7), 654.

Weaver, C. (2002). Reading process and practice. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Wegerif, R. (1998). The social dimension of asynchronous learning networks. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 2(1), 34-49.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Author Note:

Ann M. Courtney

University of Hartford

Email: [email protected]

Frederick B. King

University of Hartford

Email: [email protected]

Appendix A

Examples of Two Students’ Pre- and Postassessment Concept Maps

Figure 1. Student 1 pre-assessment concept map.

Figure 2. Student 1 postassessment concept map.

Figure 3. Student 2 pre-assessment concept map.

Figure 4. Student 2 postassessment concept map.

Online Prompts Used in EDR 344

Prompt 1

How does learning take place when an adult scaffolds in mindful ways that consider a reader’s specific needs? What does Cole mean when she states, “Teachers need to read their students’ cues as well as the text being used. Students read the teachers’ feedback and feedforward cues as well as the text they are using.”

Prompt 2

Scaffolding: Make a list of ways in which you could scaffold individual students during their reading. As a group come to consensus and number these in order of importance, that is, from the one that would predictably produce the best results to the one that may not produce many results. Discuss why you have numbered them in this fashion.

Prompt 3

Cues: The goal for readers is to be more automatic and accurate at using graphophonic cues, as well as, additional cueing systems interactively. How can you help struggling readers become readers who are fluent and who read for meaning? Your discussion should focus on the graphophonic cueing system and its integration with semantic and syntactic cueing systems to increase fluency and automaticity.

Prompt 4

Comprehension: How do teachers develop in young children a disposition for comprehension? In other words, how do teachers develop internal stimulation in children that enables them to tune in to the meaning of the text and to thoughtfully consider its connections to their world?

Prompt 5

Scaffolding Comprehension Strategies: Part of children’s connecting with literature involves considering links between their own experiences and those of the characters and personalities about whom they are reading. Your role as the teacher is to promote thoughtful exploration of book content. How do you the teacher scaffold children through comprehension strategies and book content? Be specific. Make sure you use the Owocki text in your discussion.

Excerpt from Online Dialog in Response to Prompt 4

Sun, Nov 14. 7:46 pm

Author: Katie

To internally stimulate a child to tune into meaning and comprehend just what they are reading, one must first make sure that the process of reading is an active one. By understanding the text that is being read, children must keep their own knowledge and experiences that they have had in mind while reading.

“Comprehending is an active process of using everything we know to construct a meaningful text and filtering what has been written through our own knowledge and experiences” (Orwocki) ……..By pointing out that reading is not just simply saying the words that appear on a page, but a process that is meaningful and requires active thought, this is where I feel a teacher must first touch upon when attempting to develop internal stimulation within their young students. “In classrooms in which children are encouraged to discuss what and how they read, teachers create a strong foundation for supporting listening and reading comprehension.”(Orwocki).

Note: Katie set the stage for this discussion by focusing the group to think of comprehension as an active meaning making process.

Mon. Nov 15. 11:01 am

Author: Stacy

As we have talked about many times in terms of developing a reader’s comprehension levels/skills, these strategies apply and influence a child’s monitoring of their own comprehension. .. retelling (summarizing/synthesizing), questions about/within the text, visualize into the worlds of texts, make personal connections about/between texts, and lastly evaluate ones meaning making.

“Effective comprehenders monitor their comprehension as they listen to and read text. This means that they actively consider the meaning of what they are reading; when something doesn’t make sense; they recognize it and either revise their thinking or use fix-up strategies to get back on track. (Orwocki 20-21). The best way to help children to develop these monitoring skills/strategies when reading is to model and to think aloud to your students about how and why you are using these strategies while reading to your class …..

Note: Stacy extended Katie’s meaning by making it concrete and describing specific strategies readers use as they comprehend texts. Furthermore, she introduced the group to the concept of modeling and doing think alouds.

Mon Nov 15 11:50 am

Author: Carmen

Katie and Stacy, I think you have said some really great things and I agree with them. I think when it comes to comprehension we ourselves are doing some of the things you said to make meaning and form understanding of the work we have from class. Just in these posts alone we make connections, evaluate, and visualize the context of our discussions and what we have read. Like Stacy, I think with children in the classrooms these concepts need to be modeled and shown to them so they have the ideas and pick up on them. My field experience is with younger children. …I completely agree with what you have said about connecting experiences they have in real life to their reading. …….

Note: Carmen analyzed what Katie and Stacy stated and responded to it by agreeing. She also extended that thinking by sharing what happened in her first grade field experience.

Date Mon Nov 15 5:55 pm

Author: Carmen

I think that in regards to children making connections to their world, it is easy to find books to allow them to do this. ….

Note: When no one else had contributed anything between Carmen’s initial posting at 11:50 am she extended her original thought about making connections at 5:55 pm and spoke in-depth about the importance of selecting the “just right’ book to help children make text connections to their world.

Date: Tues. Nov 16. 2:02 pm

Author: Tori

I think that a very big aspect of comprehension for everyone is the ability to apply prior knowledge to reading. I can remember as a student in elementary school using different worksheets and KWL charts. ……

Date: Tues Nov 16 2:19 PM

Author: Katie

Another important piece I feel we have not yet touched upon within our discussion is a child’s knowledge of text structure in helping them comprehend meaningful texts. …..By drawing attention to the different text structures that are seen in group, independent, shared, and guided reading sessions, children will become more internally stimulated/aware of this helpful strategy/tool that children can use to express their comprehension of story…

Note: Katie introduced the concept of text structure and developing a student’s schema for text structure through different reading formats.

Date: Tues Nov 16 3:15 pm

Author: Carmen

Meaning making is what I feel is by far the most important aspect in helping a child’s development of text comprehension. How we help children find and touch upon meaning is what the essential question is to this prompt. We have discussed thus far that active reading, knowledge of content, and texts structure are all aspects that can help one tap into meaning. .. Predicting and Confirming… Questioning….Visualizing…Most strategies operate simultaneously. I feel this is very true, and have learned a lot about this throughout our EDR 344 class and the readings that have been assigned.

Note: Carmen moved beyond text structure and discussed making meaning. First, she summarized what she thought had been discussed so far in the online dialog. Then she reintroduced the specific strategies Stacy had listed in her first entry. Carmen wrote three very long paragraphs detailing her understanding about each of the strategies.

Date: Tues Nov 16 3:26 pm

Author: Stacy

Tori, by KWL charts, I’m assuming those are the what you know, want to learn and what you learned charts right? If that is what you were talking about I definitely feel that those are an important aspect of comprehension. This goes along with what we were talking about in class today. The piece that the children would know could be something from the Guided reading groups and book walks. Going through the book walk before the students read it; they can pick out the pieces that they know. Also, the what they want to know stems off of the book walk. We need to leave the children with a question to drive them into the text. Here we can have the students come up with predictions and questions. Finally, after they’ve read the book silently, they can come back as a group and discuss what they’ve learned.

Note: Stacy clarified what Tori had meant by KWL. Then she related Tori’s KWL thinking specifically to what the discussion had been in class that day about guided reading. Stacy described what would happen in classroom practice. Eight more responses followed adding to the understanding of classroom practice and reading theory (Katie 3:33, Stacy 4:01, Stacy 4:24, Carmen 4:49, Katie 5:11, Tori 5:21, Stacy 5:32).

5:35 Carmen

Katie, I think that what you said is great. I agree with you and the book about simultaneous strategies being used when reading. I think that just from doing those two running records with the first grade children it was obvious. I think that hearing the children read gives insight into what strategies they have mastered and what they have not because they were doing things that they didn’t talk about being able to do during the burke reading interview. …

Note: Carmen related Katie’s understanding about simultaneous strategies to how a teacher would know whether that was happening. Carmen related the class experience of assessing first graders to identifying the strategies the reader would use. Twelve responses followed this entry most of them happening between 11:00 pm Tuesday and ending at 8:40 pm Wednesday. The respondents continued to discuss modeling comprehension strategies, using think alouds, and how to get readers to use fix-up strategies and self-monitor.

Date Wed Nov 17 8:40 pm

Author: Katie

Throughout our prompt we have talked a lot about strategies in helping children tune into meaning, and we have also talked a small amount about scaffolding. I know that in class scaffolding is hammered into our future teacher minds. I did want to bring up the fact that Owocki does bring up her own suggestions for scaffolding children in effectively comprehending text, on pages 35 and 36 of chapter 3. Most of these dance around the general suggestions we have also discussed in terms of scaffolding, but they are far more specific and geared towards the exact teaching/scaffolding instruction that deals with comprehension. I feel these are great teaching tools and I feel any teacher who wishes to focus on comprehension needs to look at them (right girls?). “To scaffold effectively requires that you pay close attention to the way you use talk in your instruction. Effective scaffolders teach from behind. They let children’s ideas direct the conversation and provide the adult perspective as it becomes relevant (pp36-37). I feel that this quote contributes to teacher instruction/awareness for those who are attempting to implement these scaffolding techniques in their comprehension instruction.

Note: Katie pointed out the need for the group to revisit the text in order to pay more careful attention to how to scaffold, which she felt was missed in the dialog. This point also gave the course instructor insight into areas where her instruction needed to be strengthened and directed for the following class.

Final Survey

How helpful was the online discussion in Strongly Disagree Strongly Agree

aiding you in your understanding of

literacy learning? 1 2 3 4 5 6

Question 2

What were the strengths of the online discussion group in furthering your understanding

Of literacy learning?

Question 3

How did the online discussion help you in furthering your understanding of literacy

Learning?

Question 4

What strengths did you bring to the group and the process?

Question 5

What did you learn through the online discussion that you will incorporate in your student teaching?

Question 6

In all honesty did the online discussion help you with your knowledge of literacy learning?

Question 7

In all honesty did you like the online discussion? If so, why? If not, why not?

- Additional Comments are welcome!

![]()