In their recent analysis of the complexity of clinical supervision of teachers, Burns and Badiali (2016) concluded that “university supervisors may be the most undervalued actors in the entire teacher preparation equation when one considers the knowledge, skills, and dispositions they must have to teach about teaching in the field” (p. 156). These various technical, pedagogical, and social-emotional skills run the gamut from supporting teacher candidates’ lesson and unit design skills, acting as instructional coaches and negotiating complex relationships in a school setting, to providing teacher education programs evaluative feedback on candidate performance via detailed observation rubrics and narratives (Butler & Cuenca, 2012).

However, university-based clinical supervisors have long been seen as “disenfranchised outsiders” (Slick, 1998, p. 821), resulting from the low-status afforded to field-based teacher education and those carrying it out. Too often, the expectations placed on clinical supervisors outpace the supports that institutions of teacher education dedicate to them (Grossman, Hammerness, McDonald & Ronfeldt, 2008). Unlike other clinically oriented professional fields such as social work, psychology, and counseling, by and large, the work of clinical supervisors in teacher education is assumed to be taking place successfully, with little training, oversight, leadership, feedback, or support.

This paper describes an innovative response to this dilemma: an initiative in which clinical supervisors were invited to investigate their post-observation conversations using video in a self-development group. Results suggest this approach as promising for advancing supervisors’ self-awareness of their post-observation facilitation skills that builds on prior work in professional supervisor preparation.

Literature Review

This literature review opens with a brief comparative perspective from the allied field of counseling on the preparation of supervisors. We then discuss how collaborative inquiry, a tool widely used with teacher professional development groups, can be applied in the supervisor learning context. After a discussion of video as a reflective tool with teacher learning, we offer a conceptual framework that shapes our strategy for using video to support supervisors in the clinical preparation process. Thus, we drew on research both within and outside of supervisor professional development for this study.

Supervisor Preparation: What Teacher Education Can Learn From Counselor Education

This case of supervisor preparation in the field of counseling provides a helpful comparison that highlights relatively how little preparation or professional development clinical supervisors receive in teacher education. Like teacher education, in counselor education, the goal of supervision is to promote candidates’ emerging professional vision, decision-making, and autonomy while also serving the public good by ensuring high-quality standards are being met by both pre- and in-service professionals (Goodyear & Guzzardo, 2000).

Unlike teacher education, the knowledge base for supervision within counselor education is well-established, with the first supervision workshops in the mental health professions offered as early as 1911 (Kadushin,1985). Currently, at least one course in supervision is part of the professional preparation in doctoral counselor education (Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Education Programs, 2001) and is even present in about half of master’s degree programs in counseling (Scott, Ingram, Vitanza, & Smith, 2000).

The supervision content of this preparation and training in counselor education encompasses various supervision models, techniques and formats, counselor development, the supervisory relationship, multicultural competence and issues, legal and ethical issues in supervision, and administrative skills (Bernard & Goodyear, 2014; Borders et al., 2014). In a systematic review of 11 controlled studies on supervisor training in counselor education (Milne, Shiekh, Pattison, & Wilkinson, 2011), all included feedback as the primary topic to be addressed with supervisors. For working supervisors, ongoing training is also a well-developed practice, with supervision training reported at the individual, group, Web-based, and seminar level (Bjornestad, Johnson, Hittner, & Paulson, 2014).

The value placed on supervision in the field of counseling is evident, considering the multiple ways in which it is exercised. Supervision is practiced with candidates in counselor preparation programs since they may be supervisors in the future. Counseling supervisors, after receiving the knowledge base for this aspect of professional practice, are closely supervised themselves and receive ongoing mentoring (Bernard & Goodyear, 2014). Yet in teacher education, clinical supervision is not seen as a core aspect of teacher preparation, in spite of the well-accepted importance of their role in teachers’ development (Farhat, 2016).

Knowledge Base for Supervision in Education

Although there is a long way still to go in the preparation and professional development of clinical supervisors in teacher education, some recent work sheds light on the content and formats that might be implemented. In terms of skill development, of central importance for clinical supervisors is the ability to successfully facilitate teacher candidate observation and feedback for teacher learning. Burns and Badiali (2016) identified six skills exhibited during the supervision process: noticing (picking up on important aspects of the teaching and learning going on in the lesson observed), pointing (helping the teacher see what the supervisor noticed), ignoring (selectively choosing to disregard some aspects of practice in a hierarchical, triage-like fashion), intervening (getting involved with suggestions for improvement), unpacking (breaking down lesson components for the teacher during the debrief), and processing (facilitating the teacher’s reflection on the lesson). Each occurs during the observation and feedback stages of supervision, and each ultimately needs to be carried out by the teachers on their own.

Supervisors likely vary in terms of their strengths in these six areas, and more research needs to be carried out to refine these behaviors and understand how supervisors are carrying them out. However, the skills of “unpacking” and “processing” have received a fair amount of research. The unpacking and processing steps generally are the central activities of post-observation conferences (POCs). Arcario (1994) called POCs a “canonical conversation” (p. 3). He found that the POC generally begins with small talk, then an opening move by the supervisor, followed by an evaluation, justification, and prescription sequence, ending with a closing move. The supervisor controls the conversation and is principally engaged in the analysis and evaluation of the observed lesson, rather than the candidate.

The unequal quantity of talk associated with supervisors and teacher candidates can be linked to both this predictable structure and the roles taken up by participants of the POC. Farr (2010) found that POCs contain about 36% teacher candidate talk versus 64% supervisor talk. This talk ratio parallels the type of talk generated by supervisors, which tends to be highly directive. Crasborn et al. (2011) described it thus:

[Supervisors] who use their conversational turns mainly to bring in information (i.e. ideas, perspectives, suggestions, feedback, views, instructions) have a more directive supervisory style than [those] who use their conversational turns to bring out information, i.e. by asking questions, summarising aspects of the discussion, and active listening. (p. 321)

In spite of their best intentions, supervisors tend to dominate the talk, tell rather than ask, and do the work of noticing, unpacking, and processing for the candidate (Farr, 2010; Orland-Barak & Klein, 2005). Ultimately a learned helplessness results among teachers and their disempowerment. Improving the quality of these feedback sessions depends on supervisors becoming more aware of these conversational tendencies, in general, and, in particular, their own behaviors during conference talk.

For example, the introduction of video review, carried out by observed teachers prior to engaging in the feedback session with their supervisors, has been shown to have the potential to disrupt the usual talk ratios, leading to different ways of talking (Baecher & McCormack, 2015). Thus, professional learning that could target supervisors’ awareness of their talk in post-observation feedback sessions is clearly relevant and shows great promise for supervisor professional development.

In terms of formats for clinical supervisor professional development in teacher education, recent studies have experimented with how collaborative working groups can bring supervisors out of isolation and serve as a vehicle for their professional learning. “Don’t leave me out there alone” (Dangel & Tanguay, 2014) and other studies (Baum, Powers-Costello, VanScoy, Miller, & James, 2011; Levine, 2011) have proposed collaborative peer inquiry as an effective structure for bringing clinical supervisors together in order to foster a greater sense of belonging within their institutions and to provide spaces for them to share their concerns and challenges together. Levine (2011) worked with supervisors to identify the core elements they believed were essential to effective collaborative community-building among supervisors. The ones they felt were essential were (a) establishing norms to promote collaboration, (b) building trust and familiarity among group members, (c) designing activities that allowed them to openly share practices, (d) ensuring institutional access to logistical information and shared expectations about the role of supervisors, and (e) providing time for collaboration among supervisors.

Dangel and Tanguay (2014) also studied supervisor development via collaborative groups, emphasizing the importance of structured, dedicated time for novice and experienced supervisors to meet together and learn from one another. They also recommended these collaborative meeting times for supervisors to develop a better understanding of the program and schools and to enhance supervisors’ observation and coaching skills.

Video as a Reflective Tool

Recent studies suggest there is already movement toward building communities of practice among clinical supervisors. The well-developed literature on effective professional development for pre- and in-service teachers has also clearly emphasized that it is most effective when it is carried out in participation with colleagues, embedded in their work contexts (Hunzicker, 2011; Vescio, Ross, & Adams, 2008). Peers serve as critical friends who assist one another in exploring assumptions and expanding their understanding of the issue under study. Peer inquiry among teacher groups often employs artifacts such as student work samples or videos of practice to ground their discussions. These artifacts support dynamic and iterative cycles of teacher learning, beginning with (a) representation (helping teachers view effective practices in action); (b) deconstruction (breaking down the practices to understand their technical and theoretical aspects), (c) approximation (attempting to apply the practices in one’s own teaching), and (d) reflection (looking back to understand more about what occurred and what could be altered) (Grossman, Hammerness, & McDonald, 2009).

A highly effective tool that supports each of these four learning stages is video analysis — using video records to represent practice, deconstruct practice, and self-capture for subsequent reflection on- and for-action (Schön, 1983). What video uniquely offers is the chance to stop, rewind, and replay in order to hone teachers’ capacity for marking, or noticing (Rosean, Lundeberg, Cooper, Fritzen & Terpstra, 2008). By noticing, or “marking,” educators can go back and “remark” — thus building the foundation for evidence-informed reflection.

In the case of the use of video analysis among supervisors, it is important to recognize that the positioning of supervisors as “experts” may inhibit them from either genuinely believing their practice warrants scrutiny (Barnawi, 2016) or feeling comfortable openly admitting that their practice could benefit from reflection. Video is effective for creating the cognitive dissonance necessary for supervisors to begin interrogating their own practice and considering how their ideal vision of supervision or their intended actions relate to their actual interactions during supervisory conferences. Viewing their practice alone without having to put it on display or be observed helps experienced supervisors save face and decreases both their sense of vulnerability and their resistance to self-reflection.

The professional growth of supervisors depends upon the recognition that supervision is a pedagogical skill set that can be advanced in a manner similar to teacher development. Although such peer inquiry groups are not typically found in higher education, teacher educators could also engage in collaborative peer inquiry to improve their pedagogy. We also believe that the use of video feedback could support supervisors’ self-reflective processes within the collaborative inquiry process.

In this paper, we share an initiative designed as a way to promote greater self-awareness of facilitation moves during conference talk among supervisors within a teacher preparation program. This professional development initiative was built upon two elements that have proven successful with teachers: the use of video analysis and peer collaborative inquiry. We document the process we initiated with 10 supervisor participants over two academic semesters, which had been previously piloted with one supervisor (Baecher & Beaumont, 2017). We share results from each stage of the process with reflections from the supervisors and point to some key principles for enacting this type of professional development for supervisors within teacher education settings.

Methods

Research Context

This study was conducted within a Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) Master of Arts (MA) program leading to P-12 state teaching certification within a college of education at a large, urban public university in the northeast US. Most students in the program are currently teaching while pursuing the MA in TESOL (in-service), and some are student teachers (preservice). In the program, teacher candidates complete 30 weeks of supervised teaching in English as a second language public school classrooms, across their two final semesters. Each teacher candidate is assigned a university field supervisor who observes them two times onsite at their school, and one time via video each semester, for a total of six formal observations over two semesters. After each observation, the supervisor evaluates the lesson according to a standard rubric that covers eight domains of TESOL. The supervisor schedules individual POCs for a time soon after the lesson, at which time candidates join the supervisor to debrief the lesson. Performance is evaluated by the supervisor and a grade is given for the observed lesson once the POCs have taken place.

Research Design

In order to investigate the impact of supervisors engaging in video analysis of their POCs within peer inquiry groups, a pilot protocol was first developed and analyzed (Baecher & Beaumont, 2017). In this pilot, the first author, also a supervisor, worked with an outside critical friend within the methodology of self-study in teacher education (Lassonde, Galman, & Kosnick, 2009) to support her analysis and self-reflection of her POC. They transcribed the POC and then met several times to discuss it.

That pilot enabled our research team to refine the process first before inviting a group of supervisors to participate and enabled us to create the model to begin the cycle of deconstructing practice with a group of supervisor participants. Moving from self-study to focus in this study on understanding how video analysis of feedback sessions, in tandem with collaborative inquiry, might impact supervisors, we posed the following research questions:

- What insights into their practice do clinical supervisors gain by viewing their practice on video?

- How did supervisors perceive the process of viewing their practice on video?

- How did supervisors perceive the process of sharing the findings from their self-observation with the collaborative group of other supervisors?

Our research design was exploratory and qualitative, following Punch (1998) and Creswell and Creswell (2017). We utilized participant observation, open-ended prompts in questionnaires, a small sample, and emergent coding, as they describe, and bound within the particular case of one group of supervisors in a teacher education context that is typical of other US teacher preparation settings.

Procedures. As part of routine practice in this teacher education program, all supervisors (n = 30) receive 3-4 hours of professional development each semester. The first step in this initiative was to focus on post-observation conferencing skills in one of these sessions. The idea of video-recording the POC was introduced in order to invite both the supervisor and the teacher candidate to review and reflect on it (see Appendix B). The process for recording, sharing, analyzing, and discussing the videos was as follows:

- Recording: Teacher candidates and supervisors met to discuss the observed lesson either face to face or via web conference. If they met face to face, the supervisor turned on Quicktime Player on their laptop and selected, “new video recording,” then minimized that screen. The supervisor and teacher candidate carried out their conversation in view of the laptop built-in camera. If they met online, they used Zoom, which allows up to 40 minutes of free conferencing and has a built in “record this conference” button. Once the supervisor and candidate met online, the supervisor pressed this record button. After the conversation, the Zoom file was created, which was a video recording of their video conference.

- Sharing. The videos created by the supervisors were put into a Google drive folder that is shared across our School of Education in a Google Classroom site. They were private to just each other. The videos were not viewed by anyone other than the supervisor and teacher candidate.

- Analysis. The videos could be retrieved by the supervisors and reviewed using the provided structured viewing guide (Appendix B).

- Discussion. Discussion with peer supervisors in the focus group did not involve any sharing of the videos the supervisors had analyzed. Due to the sensitivities and novelty of this initiative, it was determined that supervisors would engage in discussion about their individual experiences watching themselves rather than asking them to show each other their videos.

Data Collection. Data were collected from four sources. First, supervisors completed a written self-assessment of efficacy and skills in providing feedback to teacher candidates (see Appendix A). Second, supervisors reviewed and wrote a self-analysis of one of their post-observation conversations of their choosing, according to the provided protocol (see Appendix B). Third, supervisors participated in a 2-hour focus group discussion to share their findings from carrying out step 2 (see Appendix C). The third author of this paper was one of the 10 participants, while the first author removed herself in this round as participant supervisor to serve as a facilitator.

The second author served on the research team as a critical friend and comes from the field of psychology and counseling, thus bringing her expertise on supervisor development work from those fields to bear on this teacher supervisor initiative. She took extensive field notes during the focus group meeting, and the meeting was video-recorded and transcribed. Finally, a follow-up questionnaire about their reflections and perspectives on the entire process, from video analysis through collaborative conversations, was completed by the participant supervisors (See Appendix D).

Participants

Supervisors were made aware of the steps and expectations involved in this project and invited to participate on a voluntary basis, with the possible benefit of professional learning. They would not be paid to participate, and participation would involve completion of four parts: Supervisors (n = 10) who participated in this initiative were all employed part-time as clinical supervisors, hired on an ad-hoc basis each semester to visit, observe, provide feedback, and evaluate teacher candidates. They participated in routine professional development workshops two times per semester, but participation in this self-study was voluntary. Their profiles are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Participant Supervisors

| Supervisor | Gender | Years as Supervisor | Prior Reported Training in Supervision |

| F | Female | 2 | None |

| L | Male | 1 | Course on classroom observation |

| Y | Female | 5 | On the job feedback at workplace |

| M | Female | 3 | None |

| B | Male | 10 | Degree in school supervision |

| E | Male | 4 | None |

| S | Female | 2 | None |

| P | Female | 3 | Cognitive Coaching Seminars |

| T | Female | 3 | None |

| W | Female | 1 | None |

Data Analysis

Results of the closed-ended scaled responses on the pre- and post-participation questionnaires (Appendix A and Appendix D) were reviewed to provide a sense of any common patterns in supervisor responses, with the limitation of only ten participants precluding statistical analysis. Supervisors rated agreement to provided stems using a Likert scale of 1-5, with 1 being strongly disagree and 5, strongly agree.

For the open-ended responses in the pre- and post-participation questionnaires as well as the focus group conversation (Appendix C), we followed the principles of the constant comparative method (Corbin & Strauss, 2008), repeatedly reviewing the responses to see which themes were emerging. We began by grouping responses to the prompt questions in terms of common themes using emergent coding and via a shared Google sheet to carry this process out jointly. As axial, or subthemes emerged, we broke them down further, cutting and placing the text of supervisor responses in those sections, employing a thematic analysis. These included themes such as (a) supervisors’ beliefs about supervision, (b) supervisors’ stances toward the POC, (c) supervisors’ beliefs about the need for supervisors to reflect, (d) supervisor perceptions of video as confirmatory evidence of their practice, (e) supervisor perceptions of video as dissonant, and (f) supervisors’ experience of collaborative talk with other supervisors.

The prior knowledge we (the first and third author) had as experienced supervisors was brought to bear in the design of the question prompts and interpretation of participant responses. This insider knowledge was also utilized to interpret the responses of participants and to identify the themes that had also been suggested in the literature. In this way, the thematic analysis was based on constructivist grounded theory.

As Mitchell (2014) stated, “Constructivist grounded theorists acknowledge that the theory that is formed is grounded in the experiences of the participants; nevertheless, the researcher helps co-create the theory based on their interactions with the participants” (p. 1). Throughout the research design and data collection process, we were able to reach consensus and to work toward ensuring that our interpretations of supervisors’ experiences and perspectives were triangulated for greater validity and reliability.

Findings

Supervisors’ Self-Assessment of Skills Prior to Participation

Results of the preparticipation questionnaire revealed that almost all of the supervisor participants considered themselves as very effective in facilitating teacher learning. Eight of 10) rated themselves highly (agree or strongly agree) as being excellent supervisors who benefit their teacher candidates (TCs) significantly. However, they all stated that they were still open to continue to learn and improve in their work as clinical supervisors and indicated that they had had little to no training for the work of supervision. The two supervisors who rated themselves as good, but not excellent, stated that they were unsure of how impactful their supervision was and felt at times they left conversations not satisfied that they had supported their TCs’ learning.

The supervisors unanimously (10 of 10) agreed or strongly agreed that they felt isolated in their work, wished to have more engagement with other supervisors to discuss their work, and were willing to devote more time to professional learning. They commuted from their homes to the school sites, which were geographically diverse, and engaged with their TC in pre- and post-observation conversations at the school site or on the phone or video conferencing. They did not come to campus to interact with their TCs, as it would constitute an unnecessary third trip. Thus, they did not have the chance to even casually interact with other supervisors, staff, or faculty in the teacher education program.

In describing their vision of an “ideal” supervisor, several themes emerged. These themes encompassed how they saw themselves ideally interacting with and supporting the growth of their teacher candidates (see Table 2).

Table 2

Themes in Supervisors’ Responses to Vision of “Ideal” Supervisor

| Themes | Sample Supervisor Responses |

| Role | “Mentor”; “Coach”; “someone who can see the strengths and weaknesses of the TC”; “a person who can give practical suggestions and can offer advice for addressing specific problems” |

| Emotional Support | “being supportive,” “someone who listens and provides emotional as well as technical support” “…an ally to the teacher. It seems that teaching candidates are always stressed and need encouragement and support.” |

| Trusting Relationship | “being trustworthy”; “The relationship is also one that is important to foster so that the teaching candidate is willing to take feedback and reflect.” “be someone the teacher can feel comfortable with” |

| Format of Feedback | “I believe feedback is best given if started with a positive/strength of the student teacher, then a suggestion for improvement and ending with another compliment”; “give directed and constructive feedback” |

| Plan for Teacher Candidate’s Growth | “I see my role as a clinical supervisor to guide self-awareness, have students identify and understand their strengths and weakness, inspire them to challenge their perceived limitations of themselves and develop the vision to target end goals, and overall take greater responsibility over their own learning process.” |

While all the surveyed supervisors believed in the effectiveness of and necessity for clinical supervision in teacher candidates’ learning to teach, the formula for the feedback appeared to be the traditionally accepted “praise, offer a suggestion, then praise,” and “give concrete suggestions.” This vision of the feedback given by supervisors is consistent with the literature that has shown that POCs are so remarkably consistent in their format that they have been identified as their own genre of institutional talk (Arcario, 1994).

An inherent tension was presented in these supervisors’ responses in that they indicated they believe in and follow the canonical approach to feedback but, at the same time, hoped that the supervision process really supported the TCs’ growth and autonomy. The responses to the questionnaire about their beliefs created a background for the next step in the data analysis — how they then perceived their actual talk when reviewing their videos of their POCs.

Video Review of Supervisors’ POCs

The next phase of the research was for supervisors to select one of their video-recorded POCs and complete an analysis and reflection on that particular POC individually according to the provided protocol (see Appendix B). They then brought those findings to the collaborative inquiry group discussion scheduled several weeks later.

Through an analysis of the collaborative conversation and their written reflections, supervisors in the study appeared to view the feedback they provided along three dimensions: (a) evaluation — aligning the activities viewed in an observation to a preset list of desired teaching practices, (b) coaching — guiding the TC toward improvement and learning, which involves assessing what the TC already knows and can see; and (c) support — praising and affirming the TC’s strengths.

In the opening phase of the POC, supervisors appeared to commonly begin by asking the TCs questions and using their answers to gauge where to go next in the conversation. They stated that they believed this helps TCs feel in charge of their learning and allows the supervisors to prioritize areas of improvement. In this way, the POC was at times “unpredictable,” and supervisors had to rely on their ability to respond in the moment. One supervisor’s comment is an example of how they saw the conversations starting:

I make sure that I listen to what they are saying, a lot of active listening, no comments at the beginning and just trying to get all their points and see if they match mine and, if not, I will see what they’re talking about and try to get something out of, because that’s the time that I feel they are ready to learn. Supervision and teaching are the same thing for me — I don’t teach the lesson plan but the class; the same thing when I have a meeting with a teacher candidate, I don’t want to only cover what I deem important, but if they have a concern, let’s talk about that first.

Much like Goodyear and Guzzardo’s (2000) recognition that supervisors in the field of counseling must assist counselor trainees to be prepared to negotiate unpredictable interactions by drawing on their professional knowledge base, these teacher supervisors commented that they felt confident in scoring and evaluating “good practice” in teaching. The way that the conversations opened up and ensued depended, however, on the TC and how the two together were able to interact in the feedback session. Watching their videos helped the supervisors identify that they engage with an element of the unknown each time they enter into a POC.

Another noticing was that, as the supervisors looked at the videos of their POCs, they noted that TCs often began their conversations focusing on those aspects of practice that had been brought up by supervisors in previous conversations. They considered whether the conversations “are more of a play with a script,” with the TCs bringing up what they believe was important to the supervisors rather than the supervisors helping them to see what was important to them. This relates to the research base that indicates that the nature of the POC is more a type of formulaic talk than authentic interchange, largely because of the power differential between the TC and the supervisor. Wajnryb (1994) characterized POCs as “risky discourse” for the TC, who is “exposed and powerless,” whereas the supervisor is positioned and “empowered to hurt” (p. 33).

As they watched the POCs unfold on the videos, although most of the supervisors noticed opportunities they may have missed to foster more TC-led talk, two of the supervisors found that the video confirmed what they believed to be true in their practice — they saw themselves asking questions and providing targeted feedback, and noted that the teacher candidates were doing a lot of the analysis of the lesson on their own. These two supervisors did not note room for much improvement. For instance, one supervisor stated,

I was so pleased to be seeing [J] being able to point to a number of ways she could have set up her Do-Now activity to get students at work more quickly. We have been focused on that all semester so when we spoke it was [J] who spoke up right away and came up with other ways she could have started her lesson. I could not really see what more I could have done in this POC with [J].

Yet most of the supervisors, while finding satisfaction with some of what they observed, expressed dissatisfaction with other results of their video analysis. These supervisors noted that in reviewing their video, they were able to see more opportunities for fostering their teacher candidate’s thinking than they were able to note during the POC itself. One supervisor commented,

I really enjoyed this opportunity to step back and relisten to the feedback [M] gave about her teaching. It gave me an opportunity to remember the lesson one more time and even more ideas and suggestions came to mind. It was also very easy to see what I forgot to do, like look at student work and look back at the goals [M] had set earlier in the semester.

Watching their video brought to the attention of the several participating supervisors the significant discrepancy between how they perceived themselves leading the POCs and how they actually carried them out. They were surprised at how much they controlled the talk when they had thought during the POCs they had been only supporting the candidates’ thinking. One supervisor shared,

I was able to see in the video where I don’t always practice what I preach. I believe I want to empower the teacher to analyze her lesson, but I noticed how, in truth, I may have been too strong with my ideas, and that may have made the teacher afraid to speak openly about what she is struggling with.

Supervisors’ individual and collective reflections on their video review showed that the video was most helpful in illuminating four components of the POC: the opening, the communication that took place, the way they organized their feedback, and how the ended the conversation, presented in Table 3.

Table 3

Themes in Supervisors’ Responses to Viewing Their POC on Video

| Themes | Sample Supervisor Responses |

| Opening the POC | “I notice that I ask questions first, about how the TC thought the lesson went, how they felt about the lesson.” “The TC talks most at the beginning of the POC, when I ask about how the lesson was for them.” “I want to know how the TC thought the lesson was before I say anything. I was surprised at what they commented on first; it’s not what I would have started off with.” |

| Communication Style in the POC | “I thought I gave more praise than I really did. I can see why the TC might feel insecure after watching how I asked her so many questions.” “I noticed that the TC agrees with everything I say. I now wonder if they just want to get it over with and whether they really understand some of the things I am saying.” |

| Format of Feedback | “I saw myself giving praise and then giving a lot of suggestions.” “I asked questions but then I mostly answered them.” “I think I might be afraid of letting the TC talk too much, since they sometimes focus on something other than the lesson, and I want to make sure we are staying evidence-based on the lesson” |

| Plan for Teacher Candidate’s Growth | “In the end of the conversation I notice that I try to review two important areas I want them to make improvements in before we meet again.” “I think that the end of the conversation was where I could have let the teacher candidate restate what we had been talking about rather than me going over it for them.” |

Reviewing the video with the provided protocol appeared to be helpful to the majority of supervisors in supporting their ability to explore the stages of the conversation, the nature of their talk, the ways the teacher candidate engaged, and possible ways the conversation could have been experienced by both parties.

What Supervisors Gained From Engaging in the Collaborative Video Review

The findings suggest that supervisors found looking at the video records of their conversations to be intriguing, in some ways affirming, enlightening, and motivating in terms of a desire to further grow in their supervisory process. Just as teachers discover when analyzing their videos of teaching, the supervisors in this study found that the process of individually reflecting on the video evidence in combination with the discussion of their practices in a peer inquiry group led most to see a gap between their stated positionality and their actual behavior. Supervisors agreed that the process was consciousness-raising in terms of the role of silence, how drawing out teacher candidates in the conversation could occur, and on a larger scale, how TCs could be better prepared to enter into more dialog during POCs and decrease the formulaic aspects of the talk.

They also recognized that their POC sessions did not always hit all their objectives, and they struggled with their sense of urgency regarding their limited time with supervisees. They realized that their focus was generally attached to the lesson and that observation rather than considering a larger developmental plan. They noted that the degree to which they felt they could ultimately perform their roles operated under constraints. Hearing how others in the group reacted to their videos was reassuring and also thought provoking. One supervisor stated,

After I recorded the first one that I did and looked at it, then in the others I acted as if I was recording and it made all of them much better. After just discussing and seeing what other people do, helped me a lot when I went on to do my other conferences with the teachers I am supervising. I wish I could see more of how others handle different situations.

The sense of isolation that supervisors had referenced in the beginning of the project was alleviated, and participants in the collaborative discussion stayed for more than 2 hours, eager to hear from one another. One supervisor put it, “We do not see anybody, we do not talk to anybody [about our conversations with our teachers], so a forum like this is really helpful.”

The project also helped build stronger relationships amongst a few participants who kept in touch and started consulting with each other on ways to fill out rubrics and better serve their candidates. Video provided supervisors with a tool to self-reflect. Without the video component, little of the revelatory experiences might have occurred. Just as teachers recognize the power of video to align their intentions with their actions, supervisors, too, found that what they wished to accomplish in their conferences was not always taking place.

Limitations of the Study

Although the initiative was well-received and appeared to be a positive learning experience for the participant supervisors, there are several limitations to the study. First, due to the small-scale nature of the study and its connection to the particularities of the teacher education context — location, expectations, timeframe, and subject matter — the findings may not be generalizable to supervisor professional learning in other contexts. In addition, the lack of prior research on supervisor self-development groups using video make the testing of theories of action in regard to supervisor learning still at the nascent stage. The voluntary nature of the participation, while understandable, also limits conclusions about this project’s efficacy with other populations of supervisors.

Implications

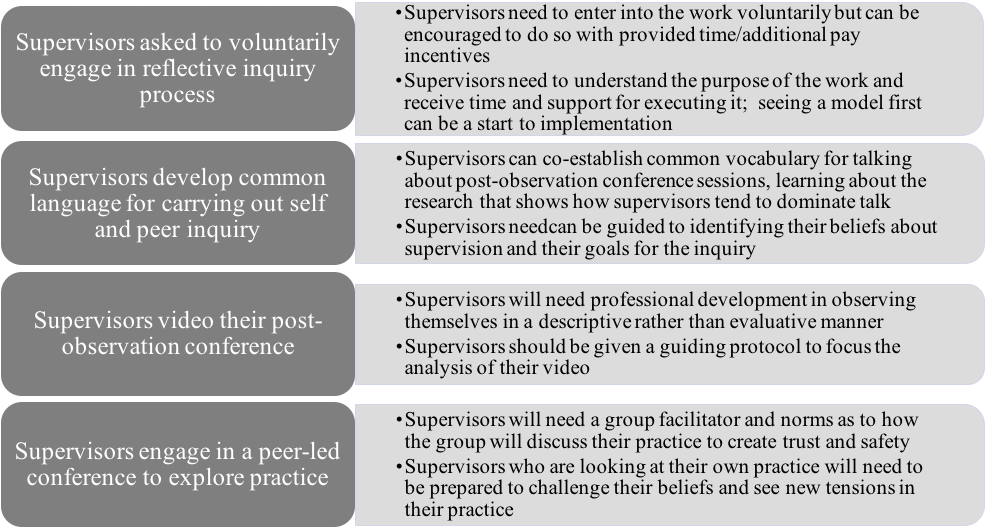

Our experiment with supervisor development presented several exciting possibilities for teacher educator learning, which could be developed in relation to local needs and contexts, but which may share some common principles. First presented in the pilot stage of this initiative (Baecher & Beaumont, 2017), we have modified it based on our findings of this study.

First, because inquiry must be true to an individual’s interests and desires to explore practice, participants must choose for themselves to enter into this reflective interaction. Supervisors, who usually are isolated in their work, will also identify a peer or peers who might constructively engage in the process with them. Together, they need to make explicit their beliefs and assumptions of their supervisory practice and identify a specific yet flexible set of goals or priorities — what they want to look at in their practice. This approach serves as the foundation or starting point of the reflection process. Together, they should also maintain a transparent, open, and critical stance concerning their beliefs and assumptions, so that exploration and insight become possible both in preparing for the interaction and during the joint reflection.

On a practical level, they must also decide how they will use the video to look at their practice and craft a protocol that suits their interests and supervisory contexts. This protocol may involve education in the use of video, the use of the protocol, or the taking of nonevaluative notes.

When engaged in the reflective interaction, participants should focus on critical incidents in the video and watch them together. Focusing on the video enables participants to confront their beliefs and assumption about their practice with evidence of what they are doing and, from this grounding, begin to consider ways of changing or experimenting with that practice.

Last, to promote supervisor development and change, both participants should engage in follow-up action, which could involve goal-setting and check-ins over the course of a supervision cycle.

Implications for Future Research

Although supervision is a consistent feature of teacher education programs, there is still not enough research on what makes it impactful (or not), who is delivering this supervision, what skills are necessary to be an effective supervisor for the long-term success of teacher candidates, or how supervisors really operate within their conferencing. It is still isolated work, and bringing supervisors together for collaborative learning should continue to emerge as an important professional development goal for teacher education. Effective practices in teacher professional learning, such as the use of video feedback and video clubs, holds great promise for future studies that also serve to benefit the participants.

Conclusion

Supporting the ongoing learning of supervisors in their use of highly sophisticated clinical pedagogy will require a tremendous increase in consideration of their professional development needs. Unfortunately, not enough attention has been paid to the professional learning of supervisors in teacher education, although we have closely allied fields such as social work, nursing, and counseling we could turn to for insight and direction.

Without a professional development model for teacher supervisors, they could be prone to the same sort of thinking that is concerning among teachers. That is, it has been noted that student teachers can emerge from early classroom experiences with surface-level insights and limited critical reflection about their teaching moments. They report that the lesson went really well or that the learners seemed to be engaged and enjoying themselves. They often say they would not change anything. The mediation of the supervisor is so important at this point in facilitating the necessary attending to what actually happened in the classroom (Bates, Drits, & Ramirez, 2011).

Over the course of reflective and analytical interactions, student teachers develop a more critical and reflective view of their teaching. The same holds true for supervisors — if they are not engaged in critical, evidence-based reflection on their supervision practice, they can tend to think everything went great and become stagnated in their skills and insights.

The challenge for teacher educators is to recognize when we are not “walking the walk,” and provide this kind of critical mediation for ourselves (Bullock, 2012; Bullough & Draper, 2004; Kilbourn, Keating, Murray, & Ross, 2005). In other words, as Johnson and Golombek (2016) noted, teacher educators also bring to our work many internalized notions about teaching and learning as well as our own experiences on the receiving end of practicum supervision. It is essential that we, too, reevaluate our approaches to teacher education at all levels (i.e., course offerings, course design, practicum supervision, assessment, etc.).

We are constantly integrating reflective exercises into our students’ courses and practical experiences, yet how often do we sit and write a reflection after a lesson, invite a colleague to observe and give us feedback, or think aloud while watching a recording of our class with a more experienced colleague? For us, the research and reflection involved in exploring supervisors’ practices and engaging them in reflecting on their work is generative, leading to other possibilities such as incorporating action research, utilizing stimulated recall with supervisors, providing supervisors exposure to cognitive coaching approach during postteaching consultations (Costa & Garmston, 2015), and employing more self-reflection and written narratives (Farrell, 2015; Golombek & Johnson, 2004) within our work with supervisors.

References

Arcario, P. J. (1994). Post-observation conferences in TESOL teacher education programs. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, NY.

Baecher, L., & Beaumont, J. (2017). Supervisor reflection for teacher education: Video-based inquiry as model. The European Journal of Applied Linguistics, 6(2), 65-84.

Baecher, L., & McCormack, B. (2015). The impact of video review on supervisory conferencing. Language and Education, 29(2), 153-173.

Barnawi, O. Z. (2016). Dialogic investigations of teacher–supervisor relations in the TESOL landscape. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1-15.

Bates, A. J., Drits, D., & Ramirez, L. A. (2011). Self-awareness and enactment of supervisory stance: Influences on responsiveness toward student teacher learning. Teacher Education Quarterly, 38(3), 69-87.

Baum, A. C., Powers-Costello, B., VanScoy, I., Miller, E., & James, U. (2011). We’re all in this together: Collaborative professional development with student teaching supervisors. Action in Teacher Education, 33(1), 38-46.

Bernard, J.M., & Goodyear, R.K. (2014) Fundamentals of clinical supervision (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Bjornestad, A., Johnson, V., Hittner, J., & Paulson, K.L. (2014). Preparing site supervisors of counselor education students. Counselor Education & Supervision, 53(4), 242-253.

Borders, L.D., Glosoff, H.L., Welfare, I.E., Hays, D.G., DeKruyf, L., Fernando, D.M., & Page, B. (2014). Best practices in clinical supervision: Evolution of a counseling specialty. The Clinical Supervisor, 33 (1), 26-44.

Bullock, S. M. (2012). Creating a space for the development of professional knowledge: A self-study of supervising teacher candidates during practicum placements. Studying Teacher Education, 8(2), 143–156.

Bullough, R. V., & Draper, R. J. (2004). Making sense of a failed triad: Mentors, university supervisors, and positioning theory. Journal of Teacher Education, 55(5), 407-420.

Burns, R. W., & Badiali, B. (2016). Unearthing the complexities of clinical pedagogy in supervision: Identifying the pedagogical skills of supervisors. Action in Teacher Education, 38(2), 156-174.

Butler, B. M., & Cuenca, A. (2012). Conceptualizing the roles of mentor teachers during student teaching. Action in Teacher education, 34(4), 296-308.

Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Education Programs. (2001). The 2001 standards. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Costa, A. L., & Garmston, R. J. (2015). Cognitive coaching: Developing self-directed leaders and learners (3rd ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Crasborn, F., Hennissen, P., Brouwer, N., Korthagen, F., & Bergen, T. (2011). Exploring a two-dimensional model of mentor teacher roles in mentoring dialogues. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(2), 320-331.Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dangel, J. R., & Tanguay, C. (2014). “Don’t leave us out there alone”: A framework for supporting supervisors. Action in Teacher Education, 36(1), 3-19.

Farhat, A. (2016). Professional development through clinical supervision. Education, 136(4), 421-436.

Farr, F. (2010). The discourse of teaching practice feedback: A corpus-based investigation of spoken and written modes (Vol. 12). New York, NY: Routledge.

Farrell, T. S. (2015). Reflective language teaching: From research to practice. Londo, UK: Bloomsbury.

Golombek, P. R., & Johnson, K. E. (2004). Narrative inquiry as a mediational space: examining emotional and cognitive dissonance in second‐language teachers’ development. Teachers and Teaching, 10(3), 307-327.

Goodyear, R.K., & Guzzardo, C.R. (2000). Psychotherapy supervision and training. In S.D. Brown & R.W. Lent (Eds.), Handbook of counseling psychology (3rd ed., pp. 83-108). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Grossman, P., Hammerness, K., & McDonald, M. (2009). Redefining teaching, re‐imagining teacher education. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 15(2), 273-289.

Grossman, P., Hammerness, K., McDonald, M., & Ronfeldt, M. (2008). Constructing coherence: Structural predictors of perceptions of coherence in NYC teacher education program. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(4), 273–287.

Hunzicker, J. (2011). Effective professional development for teachers: A checklist. Professional Development in Education, 37(2), 177-179.

Johnson, K. E., & Golombek, P. R. (2016). Mindful L2 teacher education: A sociocultural perspective on cultivating teachers’ professional development. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kadushin, A. (1985). Supervision in social work (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Kilbourn, B., Keating, C., Murray, K., & Ross, I. (2005). Balancing feedback and inquiry: How novice observers (supervisors) learn from inquiry into their own practice. Journal of Curriculum & Supervision, 20(4), 290-318.

Lassonde, C. A., Galman, S., & Kosnik, C. M. (Eds.). (2009). Self-study research methodologies for teacher educators. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Levine, T.H. (2011). Features and strategies of supervisor professional community as a means of improving the supervision of preservice teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(5), 930-941.

Milne, D., Sheikh, A., Pattison, S., & Wilkinson, A. (2011). Evidence-based training for clinical supervisor: A systematic review of 11 controlled studies. The Clinical Supervisor, 30(1), 53-71.

Mitchell, D. (2014). Advancing grounded theory: Using theoretical frameworks within grounded theory studies. The Qualitative Report, 19(36), 1-11.

Orland-Barak, L., & Klein, S. (2005). The expressed and the realized: Mentors’ representations of a mentoring conversation and its realization in practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(4), 379-402.

Punch, K. (1998). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches. London, UK: Sage.

Rosaen, C. L., Lundeberg, M., Cooper, M., Fritzen, A., & Terpstra, M. (2008). Noticing noticing: How does investigation of video records change how teachers reflect on their experiences? Journal of Teacher Education, 59(4), 347-360.

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Scott, K.J., Ingram, K.M., Vitanza, S.A., & Smith, N.G. (2000). Training in supervision: A survey of current practices. The Counseling Psychologist, 28(3), 403-422.

Shulman, L.S. (2005) Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus, 134(3), 52-59.

Slick, S. (1998). The university supervisor: A disenfranchised outsider. Teaching and Teacher Education, 14(8), 821-834.

Vescio, V., Ross, D., & Adams, A. (2008). A review of research on the impact of professional learning communities on teaching practice and student learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(1), 80-91.

Wajnryb, R. (1994). The pragmatics of feedback: A study of mitigation in the supervisory discourse of TESOL teacher educators (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia.

Appendix A

Supervisor Preparticipation Questionnaire*: Background and Beliefs about Professional Development

To what extent do you agree with the following statements? Please rate from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

- I am confident that I am an excellent clinical supervisor.

- I am always wanting to learn how to improve my work as a clinical supervisor.

- I have been offered training on how to carry out my work as a supervisor.

- I often feel isolated in my work as a supervisor.

- More time for me to visit my teacher candidates would increase my impact on their practice.

- I find having to give a number grade to each lesson I observe interferes with my coaching role.

- I am willing to find the time for more training on supervision.

- Teacher candidates really benefit from my supervision.

- The role of the clinical supervisor is essential in teacher candidates’ learning to teach.

Free Text

- How many years have you served as a university-based clinical supervisor?

- What prior/concurrent experiences have you had that placed you in a position to provide observation and feedback to teachers?

- What training or coursework have you engaged in specifically focused on instructional supervision (classroom observation, coaching, mentoring)?

- What is your vision of an “ideal” clinical supervisor?

- What is your philosophy of clinical supervision?

- What are “ideal” styles of supervisor communication with a teacher candidate?

Appendix B

Analyzing Post-Observation Conference Talk

Your Name (Supervisor):

Teacher Candidate’s Name:

| Features | Video Analysis | |

| What was the nature of the Teacher Candidate’s Talk? | Your general impressions | |

| Questions you heard the teacher candidate asking | ||

| Discoveries you saw the teacher candidate making | ||

| What was the nature of the Supervisor’s Talk? | Questions you heard the supervisor asking | |

| Suggestions you heard the supervisor making | ||

| Supervisor’s Use of Praise | ||

| What were the Phases of the conversation the supervisor seemed to move through? | ||

| Was there use of the lesson plan? | ||

| Was there use of student work? | ||

| Body language and back-channel cues from supervisor or teacher candidate? | ||

Your:

from doing this analysis. | ||

Appendix C

Collaborative Inquiry Group Questions: Self-Analyzing the Post-Observation Conversation

Please read over these questions, and we will review them together at the focus group session.

- What did you notice about the nature of the teacher candidate’s talk in your conversation?

- What did you notice about the nature of your talk in your conversation?

- What were you aware of doing to facilitate the teacher candidate’s thinking while carrying out the conversation (during the conversation itself)?

- What were you aware of doing to facilitate the teacher candidate’s thinking while analyzing your conversation (reviewing the video)?

- How did you know that your feedback caused candidates to think more deeply about their lesson?

- What were you feeling while carrying out the conversation (during the conversation itself)?

- What were you feeling while analyzing your conversation (reviewing the video)?

- If you could do this conversation again, what would you do differently?

- What role did you want to play for this candidate?

- How did you see yourself enacting that vision?

- What are your take-aways/learnings/thoughts about doing this video analysis?

Appendix D

Reflection on Collaborative Group Development for Supervisors

To what extent do you agree with the following statements? Please rate from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

- Looking at the video of my post-observation conversation was a valuable activity.

- Looking at the video of my post-observation conversation was an uncomfortable experience.

- I never want anyone to look at my video.

- I would like to be able to see someone else’s video.

- I wish I could see a “model” video of a post-observation conversation.

- I was able to see practices in my video that I believe are effective for teacher candidate learning.

- I did not feel I could effectively analyze my own post-observation conference video.

- I think working in pairs to exchange videos would be a helpful learning experience.

- I would want to do this task again.

- I experienced a disconnect between what I thought I was doing in my post-observation conversation and what I really saw I was doing.

- I didn’t need anyone else to look at my video to still learn a lot from the task.

- Discussing our post-observation conversations in the focus group helped me see my practice in new ways.

- Supervisors should have the opportunity to participate in self-review combined with a peer discussion as we had in the focus group.

- My confidence in my skills as a supervisor has increased as a result of this experience.

- Supervisors need more training in communication techniques for the post-observation conversation.

- I need more training in communication techniques for the post-observation conversation.

Free Text Questions:

- What did you notice about your communication style in your post observation conference that you think you would want to improve on?

- What did you notice about your communication style in the focus group conversation that you think you would want to improve on?

- What did the video analysis and the self-assessment of communication style inventory make you reflect on in your style of supervision?

- How aware are you of your conversation during the post-observation conference (body language, choice of words)?

- How did the peer interaction support your self-assessment?

- What kind of professional development do you think would deepen your skills as a supervisor (coaching techniques, deeper understanding of current research in teaching, greater familiarity with the teacher education program)?

![]()