“Open” is often evoked as saving the educational complex from a failing and outdated system unable to meet the demands of 21st-century learners. Whether open manifests itself in open access to books or other resources, open-ended curriculum, open source development, or open learning that crosses formal and informal educational contexts, the concept of open has promised unbridled educational access and possibility.

For the past 5 years, we (the authors) each have been involved in a professional learning opportunity for educators designed with the promise of open as one of its core components. In the Connected Learning Massive Open Online Collaboration (CLMOOC; http://clmooc.com), an experimental professional learning experience initially sponsored by the National Writing Project (NWP), our engagement has involved taking up various roles and practices, from coparticipants to participant-facilitators and researchers. Foregrounding the openly networked principle of connected learning (Ito et al., 2013), CLMOOC participant-facilitators invited educators across the globe to join them in making, sharing, connecting, and reflecting across open, online platforms, learning about connected learning by experiencing it firsthand.

Video 1. Compilation of nine CLMOOC invitation videos made by seven participants, 2013-2014.

For all that open has enabled and taught us from our work participating in and studying the open learning of educators engaged in the CLMOOC (Smith, West-Puckett, Cantrill, & Zamora, 2016), open is not sufficient and should not be the ultimate goal for professional development design. To illustrate that claim, we describe a critical case study and two professional learning facilitation practices that emerged in CLMOOC to support open and participatory learning: inviting for diversified participation and affirming for reciprocal engagement. While necessary, we have found these facilitative moves are still not enough to substantially remake learning relationships in open online professional development.

Thus, we urge teacher educators to move beyond notions of open in favor of designing for “connection” through what Bjogvinsson, Ehn, and Hillgren (2012) called an “infrastructuring strategy.” Infrastructuring for connected learning is an ongoing process of fully integrating educators into the experiences of indeterminate and unpredictable professional learning.

To illustrate infrastructuring professional learning practices, we identify two additional facilitative moves made in CLMOOC: coaching toward imperfection and curating relational infrastructures. These practices can support the development of new connected configurations of humans and objects as well as the emergence of individual and shared meaning-making and professional learning pathways.

Openness for Educators and Adult Education: Theory, Practice, Critiques

In open learning the central focus is commonly placed on the needs of the learner as perceived by the learner. Open learning involves but is not limited to classroom teaching methods; approaches to interactive learning (Mason, 1991); formats in work-related education and training (Bowen, 1987); cultures and ecologies of learning communities (Chang, 2010); and development and use of open educational resources.

Open learning characteristically allows for multiple or alternative learning pathways. With the dawning of online and networked learning opportunities, open learning has been associated with additional qualities and values for openness: accessibility, asynchronous engagement, participation, self-determined engagement, and freedom of pace (Jenkins, 2006; Thomas & Brown, 2011).

Connected learning as a framework advocates for open in these many ways — open to individual pursuit of interests, openly networked (meaning offline as well facilitated online), open to the shared purposes that emerge as groups form, and so forth (Ito et al., 2013). This educational design framework stemmed from ethnographic studies focused on how youth learn in richly networked digital environments (e.g., Ito et al., 2009). It highlights how learning that is interest driven with opportunity to produce in networked and peer-based communities can support youth in making critical connections in their lives and across connected communities (Livingstone, 2008).

As a framework that is informed by youth who were using digitally networked tools, connected learning encourages educational design that promotes the use of these tools within openly networked spaces where production and peer connections are supported. Researchers engaged in connected learning posit that by connecting the shared interests of learners (youth and adults alike), individuals can deepen networked connections with each other, resources, and within larger communities of practice (Cantrill & Peppler, 2016; Davis, Ambrose, & Orand, 2017; Davis & Fullerton, 2016; Schmier, 2014; West-Puckett & Banks, 2014).

Connected learning’s primary goal is the creation of more democratic futures, and it offers a participatory framework for designing learning experiences that follow individual learners’ interests — connecting learners through shared purpose and passion. In this piece we argue that connected learning’s initial impetus toward openness and responsiveness can be supported with an infrastructuring strategy for designing learning experiences that are intentionally fragmentary and incomplete. Taken up in designing adults’ professional learning, an infrastructuring strategy presents connected learning opportunities that are ever-in-the-making and in-the-unmaking, and they offer ways of orienting teacher learning around democratic and participatory ideals. This kind of professional learning can be transformative not because the design is openly networked, but precisely because learning is inherently rooted in teachers’ connection-making activity among colleagues, materials, practices, disciplines, and so forth.

MOOCs: Uptakes of Open in Higher Education

MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) have been a primary way higher education has taken up appeals for open learning (Losh, 2017). As MOOCs have evolved, two distinct types developed: those that resemble more traditional courses with lecture and quiz based sequences with required textbooks (xMOOCs, see Siemens, 2012) and those that emphasize connectivist philosophy in their design and run (cMOOCs, see Siemens, 2012; Smith, Dillon & Zamora, 2017). Siemens’ (2013) further distinguished the two, explaining “cMOOCs focus on knowledge creation and generation whereas xMOOCs focus on knowledge duplication” (p. 8).

In the xMOOC design, open often refers to an opening up of classrooms walls, via platforms such as Coursera and EdX, so that more learners can access traditional university instruction that flows from experts to novices (Glance, Forsey, & Riley, 2013; Kolowich & Newman, 2013) and is evaluated via automated quizzes and peer-reviewed assignments (Guzdial, as cited by Bali, 2014). In the cMOOC model, however, open signals an opening up of meaning-making pathways, as knowledge is cogenerated and moves laterally among participants and is in a constant state of becoming.

The organizers of cMOOCs operate as well-informed process hosts rather than authoritative content experts. Instead of using a learning management system (LMS) to deliver information and assignments, they promote connectivity and provide a repository for participant work (Bali, Crawford, Jessen, Signorelli, & Zamora 2015).

Ethical Concerns of Open and MOOC/cMOOC Critiques

Despite the learning possibilities enabled through an ideology of connectivity and the digital technologies that support collaboration over time and space, critiques of openness and open learning point to the ways that open culture can stand in for dominant culture, erasing culturally specific ways of knowledge-making and further perpetuating social inequities.

For example, Christen-Withey (2014a, b) argued that open can be a violence, as it treats cultural information as disembodied data without regard to its originators’ purpose, audience, and context. She pointed to indigenous practices of covering the eyes of the recently deceased, noting that family and community members may not have the ability to control how images of their loved ones are shared and circulated on an open web during a period of mourning. Thus, she called for varied access models that allow electronic communities to negotiate their openness, arguing that closed or temporarily closed are ways of doing open, as these are points on a continuum, not binary opposites.

Similarly, Shah (in Worth, 2015) raised questions about the amorphous nature of open learning: “What are we opening, whose cause is it serving, and what are the longer and historical implications of building open systems?” He posited that the idea of the closed university is a fiction propagated by those who were losing power from the diversification of public universities, a fake crisis that could be solved through the creation of open, online learning opportunities. Open, he argued, can be more easily monitored, and surveilled and can minimize the public university’s democratizing function (see also Shah, 2017).

Critiques of open learning extend to MOOCs as well, because open online courses and collaborations are particularly susceptible to commodification and the privileging of corporate interests over the needs of the learners they are meant to serve. Weller (2014a, b) characterized the melancholia open learning advocates feel about the movement of MOOCs from the periphery to the center attention — a move evidenced by the proliferation of articles about MOOCs in The Chronicle of Higher Education. He pointed to the ways educational corporations have clamored for a share in the market, treating learners like customers whose buying power is their greatest asset.

The National Writing Project’s cMOOC

Drawing on a 44-year history of teachers teaching teachers to educate and empower the profession (Lieberman & Wood, 2003), the National Writing Project’s foray into the world of cMOOCs in the creation of the CLMOOC (see Zamora, 2017), foregrounded NWP core teacher leadership principles of designing teacher development of learning alongside each other as colleagues and pursuing inquiries rather than predetermined outcomes (Lieberman & Friedrich, 2010).

Conceptualized as a “curriculum*-in-the-making” (Roth, 2013), participant-facilitators used the connected learning framework, including the design principle openly networked, to engage participating teachers in the learning principles of following their own interest-powered lines of inquiry and finding shared purpose with others. These activities engaged a broad and diverse international group of teachers-as-makers in a remix as professional learning practice, refusing notions of learning that are reproductive, static, hierarchical (Smith et al., 2016; see also Gursakal & Bozkurt, 2017).

Over the course of 4-6 weeks each summer from 2013-2017, CLMOOC activity was prompted by iterative “makes” organized into Make Cycles. Make Cycles began with an invitational prompt to make within a theme such as “make a meme,” “hack your writing,” or “create a five-image story.” These prompts were sent via a broadcasted newsletter, alongside examples (or mentor texts, as many CLMOOC English teachers call them) and related tools and resources. Though the intention of the learning community was for teachers to learn more about the connected learning values and design and learning principles, Make Cycle prompts intentionally did not start with connected learning theory. Instead, taking up the connected learning design principle of production-centered learning, they supported theorizing of connected learning through a process of making, sharing, and reflecting.

In an invitation published in the English Journal to encourage teachers to participate in CLMOOC, Sansing (2014) emphasized these attributes of play, maker practices, risk-taking, and invention as premier reasons teachers would be interested in engaging in this cMOOC (see also Foote, 2013, and Wohlwend, Buchholz, & Medina, 2017, who made similar appeals).

Make Cycles were designed to be open-ended invitations to make, compose, play, learn, and connect. Participants could choose to enter into a cycle at any point, coming in and out as per interests and availability, as Make Cycles were designed to be open and iterative rather than sequential. They also could participate by posting and conversing through any platform they desired. In 2013, a Google+ Community was established, as was the #clmooc hashtag on Twitter. In 2014, a Facebook Group was started by a participant, as was a Flickr following. From 2013-2015, participants could also have their personal blog posts added to a central blog feed. In these ways, the boundaries regarding where participation could take place were intentionally designed to be open and networked.

Facilitation roles were dynamic in CLMOOC, as everyone was first and foremost a participant; the team of NWP teacher leaders working on the initial design were asked to take on facilitation roles in the design and prototyping phases, and then others were encouraged to do so through self-sponsored activity throughout the Make Cycles. By 2015, teams from local writing project sites, as well as educators from partner organizations such as the National Park Service and KQED Education, took turns facilitating Make Cycles in CLMOOC.

The CLMOOC continues to this day outside of the National Writing Project’s guidance and facilitated by volunteer CLMOOC participants who continue with the initial impetus at http://clmooc.com. Thus, for our discussion, we consider a participant-facilitator as someone who makes facilitative moves, not someone who was designated with a particular, permanent title or status.

At the end of the first CLMOOC in 2013, participants who had taken up facilitative roles at various times collaboratively created an interactive guide for “Making a MOOC: What We Learned in #CLMOOC,” which detailed the structures for participation that had developed over the summer. From 2013 to the present (2018), these participation structures have been formalized as malleable components and flexible events within each Make Cycle. Descriptions of these written by these early participant-designers are available in the interactive Figure 1.

Figure 1. Interactive ThingLink titled “Remix the CLMOOC: A Resource Collection” collaboratively made by participant-facilitators of CLMOOC.

In previous research that focused on the ways CLMOOC participants composed multimodal and multimediated artifacts, collaborated and iterated across online spaces, and distributed their writing across differing digital platforms (see Smith et al., 2016; http://www.mdpi.com/2227-7102/6/1/12). We documented how the “living curriculum” unfolded in unpredictable ways. This unpredictability was partially due to a common practice that emerged among participants — remix.

Remix became apparent as a primary composition practice for learning, and it functioned to spur further writing, making, and relationship building as remixes burst and drifted across CLMOOC. As teachers leveraged CLMOOC participation structures for their own purposes and application to classroom teaching through remix, the goal to keep CLMOOC in-the-making was achieved. Remix was found as a practice of production and process of learning, and it exemplified networked participatory learning and promoted functional, critical, and rhetorical approaches (Selber, 2004) to educators’ transliteracies (Stornaiuolo, Smith, & Phillips, 2017).

Addressing Issues of Open in Participatory Design: A Need for Infrastructuring

Although the name has remained over 5 years, the moniker of MOOC never sat easily with the initial participant-designers or many of the participants since and became a site of early remixing. The “C” for course was purposely rewritten to emphasize certain inherent values, that is, that CLMOOC is a collaboration and not a course. The “O” in online was reconceptualized to highlight work that happens both on- and offline in hybrid ways, connecting to a range of local and distributed communities of practice.

The “O” for open in MOOC was essentially the only term that participant-designers held in high regard as they imagined the possibility of designing for emergence and responsiveness rather than predetermined outcomes. CLMOOC was also largely influenced by other connectivist, open, online opportunities in the larger field of cMOOCs, such as #change11, #etmooc, #DS106, #rhizo, which all embraced a social way of learning while questioning its commodification.

From our continued engagement with CLMOOC data, we have come to realize, however, that open is not enough. As design principles, open and participatory failed to push the CLMOOC far enough in understanding professional learning as an ongoing negotiation that serves the individual and communal needs of learners.

Bjögvinsson et al.’s (2012) “infrastructuring strategies” can assist in pushing us beyond “open” and “participatory.” Infrastructuring acknowledges both human and nonhuman actors (objects, technologies, materials, etc.) that are at play in the production of any event. Infrastructuring underscores the notion that events, in this case professional learning events, are always temporary organizations of materials, resources, peoples, and objects. They should be understood as fragmentary, contingent, and structured for possibility — continually open to being undone and redone by participants.

In fact, in-the-making and in-the-unmaking relationships between designers and users are renegotiated in this space. As users of objects become makers of objects, design is not a punctual event; rather, it emerges and unfolds over time and space.

Bjögvinsson et al. (2012) posited that traditional models of participatory design segment the design process in ways that separate designers or organizers from participants who field test and inform a redesign. Through infrastructuring, however, design can be understood as a mutually constitutive activity — a set of relationships that emerges among people and objects over time.

Infrastructuring, then, points attention to the intentional gaps designer-participants leave in processes of participatory design. In the case of professional learning, these gaps include the pedagogical decisions they leave undetermined and the ways they make room for a diversity of educators in the creation of objects or events. As such, Bjögvinsson et al. (2012) raised the following questions to guide thinking about designing for possibility:

- How do we bring participants into the object (in our case, CLMOOC as a professional learning event)?

- How do we make it malleable?

- How are the processes of infrastructuring made publicly/visible?

- How is it made open to controversies and contested experience?

The initial NWP educator-designers did use open participatory design (Grabill, 2001; Spinuzzi, 2005) as a heuristic for building a massive open online collaboration for those interested in learning about connected learning. Yet, by taking up infrastructuring for professional learning, educators can move beyond static notions of predetermined outcomes and fixed objects while supporting the emergent property of people, tools, texts, and events.

Infrastructuring prompts continuous involvement with all participants in the design and redesign of professional learning events. Perhaps most importantly, infrastructuring allows designer-participants to imagine open as a series of negotiated and contested material and interpersonal connections as opposed to a fixed state of being that is predetermined and preplanned in professional learning.

Responsive Remix: Three Rounds of Inquiry

In this critical case study, we engaged in three rounds of data collection and analysis guided by an ethic of responsive remix. In brief, first, we returned to a focal week in 2014 for which we had traced and coded data visually in a previous study focused on the relational practices of remix composing (Smith et al., 2016). We then, as a second round of data collection and analysis, sampled the development, diversification, and diffusement of facilitative practices over previous and subsequent iterations of CLMOOC from 2013-2017. As a third round of inquiry, we used remix methodology (Arola, 2017; Markham, 2013, 2017a) to create critical cases and remixed media artifacts in order to be responsive (Green, 2014) and pay homage to the CLMOOC community by utilizing its remix practices to introduce these artifacts in new research contexts. Our analysis revealed a subtle shift from facilitative practices intended to elicit fuller open participation to those grounded in creating flexible structures to support the remixing and development of new learning configurations, moves that gesture toward an infrastructuring strategy.

Round 1: A Close Look at Facilitative Practices

When we initially approached the distributed, growing number of teachers’ posts and conversations across platforms in CLMOOC, our research questions were focused on how particular prompts and guidance from participant-facilitators played out across the community, and we focused on one Make Cycle themed as Make Five-Image Stories (see Smith et al., 2016, for further details). We chose this cycle because the data were most readily available and publicly visible across social media platforms at the time. Also, during the selected week, we had each participated peripherally in CLMOOC, but had not, ourselves, taken up participant-facilitator roles.

This first round of data collection and analysis entailed culling 370 CLMOOC participant created artifacts or “makes,” 333 conversations about connected learning and writing-as-making, and 1,441 social sharing and favoriting actions. These were drawn from links and posts from Twitter (n = 678), a Google+ Community (n = 105), a Facebook community (n = 19), and self-selected blog posts that were fed to a communal repository (n = 5), as well as the CLMOOC Make Bank (n = 21; https://clmoocmb.educatorinnovator.org).

Drawing on visual circulation analysis methods (Farman, 2012; Gries, 2013) and guided by a transliteracies methodology (Stornaiuolo et al., 2017), we used collaborative, interactive visual mapping software called MindMeister (https://www.mindmeister.com) to log each make and conversation as entries and to analyze the relationships between the designed participant structures, facilitative moves, and participants’ makes and posts.

The Mindmeister platform allowed us to engage in visual descriptive and attribute coding (Saldaña, 2013) of each entry on the interactive map (see Video 2). Each entry was logged for attributes including profile name, timestamp, and link to original post and coded with relevant visual icons as descriptive content and function — as they were explicitly identified by participants in posts, comment threads, and tweets, or interpreted by the team of researchers (which were noted as such).

Video 2. Brief video of the interactive visual map of the logged and coded makes and conversations at multiple views.

Further details of Round 1 data collection and analysis are detailed in our previous work (Smith et al., 2016). In brief, this process allowed us to cull and view the 1,284 entries representing 1 week’s worth of activity in CLMOOC at a glance categorically, relationally, and chronologically. We could also engage in multiple scalar views: We could view the activity as a whole, in chronological sequences of interaction at a proximal view, and via the interactive links, directly at the particular posts and artifacts (see Video 2).

Round 2: Sampling the Development of Facilitation

During CLMOOC 2013-2015, trace data were also produced in weekly open, publicly recorded Google Hangout design meetings with volunteer participants who were taking up participant-facilitator roles for each Make Cycle. These data included the videos, transcripts, and artifacts made during these planning sessions. In addition to participant structures, learning prompts, and repository management, these sessions captured the intentional participatory design and infrastructuring activity, including facilitative orientations and moves. In returning to our original research questions regarding how particular prompts and guidance from participant-facilitators played out across the community, we found it important to revisit these meetings in relation to the week’s worth of activity from Round 1’s collection and coding. Particularly, we revised activity coded as facilitative, including request for engagement (including help or discussions), shout-out/share, bless/thank/praise, and facilitation, which included the subcodes invitation and affirmation (see Appendix A). We were also interested in how these moves played out in interactions during CLMOOC’s run each year.

Using a remix sampling method that Markham (2017a) argued is a connective (or online) ethnographic tool that necessitates and demonstrates close contextual understanding of the group or community of interest, each researcher on our team returned to a different year of CLMOOC and sampled interactions and planning meetings. We returned to juxtapose these sampled snippets with the focal week’s analysis in Round 1 and with each other. Guided by Arola’s (2017) ethic of care for remix developed from American Indian thought, for each juxtaposed sample, we “consider[ed] the web of relations from which preexisting texts emerge and are rearticulated” (p. 282). This approach involved analyzing these relations for resonance and dissonance with the trends in facilitative moves we had identified (Stornaiuolo & Hall, 2014; Stornaiuolo et al., 2017).

Round 3: Responsive Remix

In a third round of inquiry, we more overtly engaged in remix as a connective ethnography method (Markham, 2013, 2017b) to create critical cases and remixed media artifacts. Researchers engaged in communities with whom they are studying, Green (2014) argued, must be responsive to the communities ways of interacting and being. Called a “double dutch methodology” from the jump rope game, she described the work of a participant-researcher as one who seeks to learn the timing and rhythms of the playing field and engages in alternate perspectival footings inspired by the activity with participants with whom they coproduce “contextually stylized and improvisational method[s]” (p. 158). Such work moves away from prescribed data collection and analysis approaches and toward exploratory, responsive methods that position participants and researchers in side-by-side relationships. We found this particularly important as participant-researchers in a community that foregrounded learning alongside and fluid roles.

As remix was found to be at the heart of interaction in CLMOOC in our previous research (Smith et al., 2016), we engaged in multiple experimental remixes, engaging Markham’s (2013) five modes of qualitative remix inquiry of playing, borrowing, interrogating, moving, and generating. Some of these remixes are found in this article, while others were essential in our sense-making of our findings but lay on the proverbial cutting room floor. Still others were set loose within the CLMOOC community for their comment and response —checking to see if they were resonant with the community.

For those we have included here, we connected (again) with participants to ask how they would like to be named, cited, and recognized in the writing of this article. We have approached the work this way to honor participants’ rights to be connected to the work they produced as “amateur artists” of the internet (Bruckman, 2002). Participants either requested to have their online identities remain connected to their professional learning artifacts by using their first names or indicated they would like a pseudonym. In such cases, following Bruckman’s continuum for reporting internet research, we used a “moderate disguise” of their work by additionally altering the wording of quotations and avoiding the use of searchable images of their makes and, instead, remixed these images into collages or videos.

Findings

Our experiences participating, designing, and facilitating within CLMOOC have led us to question open as a category or a fixed point of reference for transformative professional learning for educators; instead, we have come to view open as a set of relationships between participants, tools, ideologies, and artifacts that can emerge through participatory design of professional development experiences. Following Grabill (2001) and Spinuzzi (2005), this paper reports the facilitative moves that set the conditions for an uptake of openness as participatory design in CLMOOC. It illustrates how CLMOOC used participatory design as an opening strategy to (a) promote ongoing iteration through making and remix practices that operate across sociomaterial domains and (b) enable reflexive collaboration to blur boundaries between participants and designers, affording the coconstruction of a shared space.

It then illustrates what emerged in these participatory conditions, from which participatory open design was necessary, yet not sufficient for reaching the transformative learning community goals. With this in mind, we set an agenda for an infrastructuring strategy toward connection.

Participatory for Open

How did CLMOOC respond to notions of open learning? While structures emerged that supported different types of connectivity, we found that particular kinds of facilitative moves were essential for encouraging shared responsibility for codesigning an event-in-the-making. To encourage playful interaction with and continued interrogation of Make Cycles, participant-facilitators and participants themselves continually and intentionally encouraged their coparticipants to engage and also to facilitate the cMOOC.

Traditional logics of professional development (a) operate on the principle that outside facilitators know best what an educator needs and how to meet those needs, (b) expect teachers to produce particular kinds of evidence of their engagement in a curriculum, and (c) work to keep experts and novices in their respective locations of power. The fluid facilitative roles and ongoing facilitation moves in CLMOOC, we found, were essential to working against the histories and traditional norms of professional development, which passively subvert an open ethos.

Five variations of fluid facilitative moves emerged in our data: inviting for diversified participation, affirming for reciprocal engagement, fracturing professional identities, coaching toward imperfection, and curating relational infrastructures. In an attempt to alleviate fellow participants’ fears about participating in CLMOOC in the right or in the wrong ways, participants used a facilitative move of inviting for diversified participation, a move that acknowledges personal and professional demands for educators’ time and attention, authorizes varying types and intensities of participation, and asks them to develop personal measures of performance for themselves and for the collective.

Affirming for reciprocal engagement involves recognizing a diversity of responses to those invitations in a way that surfaces additional connective threads and constellated possibilities for continued connection. Fracturing professional identities is a move that seeks to intentionally divest and redistribute power in service of building more horizontal networking and knotworking (Fraiburg, 2010; Ingold, 2015; West-Puckett, Flinchbaugh, & Herrmann, 2015) opportunities in an open learning community.

Our example of fracturing, however, shows that such moves can be both liberating and disorienting for educators. While fracturing expunged singular notions of expertise in CLMOOC, distributed and decentralized collective knowledge-making infrastructuring tactics were needed to fill that void. Thus, both coaching toward imperfection and curating relational infrastructures evolved as necessary infrastructuring practices. These intentional facilitative moves intentionally preserved the space of the void left by the erasure of expertise and provided connective structures for participants to surface their personal and connected learning pathways.

Each of these professional learning facilitation moves exists on a continuum that moves from open and participatory learning to relational and connected learning. While inviting and affirming are essential practices to support the emergence of open online communities, coaching toward imperfection and curating relational infrastructures are facilitative practices that can be taken up as part of systematic infrastruring strategies. Both coaching toward imperfection and curating relational infrastructures offer flexible, visible, connective structures that educators can use to develop divergent relationships and practices with other educators, with unfamiliar composing technologies and with more open-ended aims of professional learning.

Inviting for Diversified Participation. Using a connected learning frame, participant-facilitators actively worked to invite all participants to explore their own personal and professional interests and commitments and to ally with others who shared those interests. These invitations affirmed that any level of participation was perfectly acceptable, working to lift some of the burden educators may feel about engaging or not engaging what is deemed to be “correctly” in a cMOOC experience.

Inviting for diversified participation pushed participants to extend and strengthen their connections both internally and externally, to make new connections with texts, technologies, ideas, processes, and people, and to leverage the massive potential of the open web. Participants likewise engaged in these invitational facilitative moves. In the focal week of study, our analysis of the remix modalities revealed 20 invitations to join in the week’s Make Cycle invitation, 13 of which were issued by participant-facilitators and seven of which originated from the participants themselves.

Over the course of the week, these invitations reverberated through the CLMOOC’s platforms of Google+ and Twitter in the form of 11 Google+ stars and eight Google+ reshares, as well as 18 Twitter stars (now hearts) and 26 Twitter retweets. In total, 63 invitations to join CLMOOC’s formal and informal events were recirculated in the community by CLMOOC participants. These invitations were distributed and redistributed from multiple channels to create a cacophony of calls to participate, which echoed across platforms over the course of the focal week.

The facilitative practice of inviting for diversified participation emerged in 2013. It was explicitly discussed in design meetings and surfaced in newsletters written by participant-facilitators. For instance, over the course of CLMOOC, visible participation waxed and waned as participants often dropped in for a week and produced intensely or casually commented every other week on a post or were inspired to make when an invitational newsletter grabbed their attention.

A participant-facilitator Joe, drafted an open newsletter message of encouragement that worked to honor the pace and intensity of all contributions, even acknowledging the contributions of lurkers, participants who were watching the cMOOC unfold without ever posting, commenting, or resharing:

This is just a note to say that your participation so far has been perfect!

If you’ve lurked, that’s perfect! You are learning while you lurk, waiting to jump in.

If you’ve been posting like mad, you’ve been leading and making our community more inviting! If you’ve been hot and cold in #clmooc, posting in fits of productivity and disappearing for a while, that’s great. You have kids to feed, dogs to walk, and laundry that doesn’t fold itself, after all. We get it. Even when you’re catching up on your beauty sleep, you help make #clmooc massive! Regardless of how you’ve participated, consider yourself caught up and ready for your next (or first) creative act in #clmooc. You’re ripe for your next (or first) connection.

This message reminded all of those with some connection to CLMOOC, even the most tangential connection, that participation did not have to follow anyone else’s metrics, expectations, or pacing.

Invitations to participate in diversified ways continued over the years to authorize varying types and intensities of participation and to acknowledge personal and professional demands for educators’ time and attention. These facilitative moves included invitations to make in collaborative and parallel ways with CLMOOC by participants who had not taken up any formal facilitation role.

Such invitations contributed further diversified ways to participate in CLMOOC. For instance, in 2014, a participant, Scott, posted in the CLMOOC G+ community:

Hey #clmooc-ers. Much gratitude for all of the game/sightseeing suggestions. You’re such a generous bunch. I love it. Here’s one last game, if you care to play. In lieu of the #25wordstory conversation, write a #15wordstory for the image. I did mine in PicMonkey, but feel free to just reply to the post. If you want to try PicMonkey, you can find brief directions by going to tinyurl.com/learningful. Then look at the doc, “The Learningful Challenge, part 2.” You can also find the image in that folder, so you can drag it into your drive and open with PicMonkey. Thanks all.

Although no one directly commented on his invitational post, within the next 24 hours across the G+ community and on Twitter, 10 remixes of the image were posted with the #15wordstory hashtag referencing Scott’s invitation. Video 3 shows these remixes in the order they were posted in the community. Serendipitously, a new story unfolded across the individual posts. In these many instantiations of invitations, participants — those who had taken up formal participant-facilitator roles for this Make Cycle and those who had not — worked to lay not just a low bar of entry (something explicitly discussed in the designing meetings), but also an openly flexible door frame around what it meant to participate in CLMOOC.

Video 3. Ten #15wordstory remixes responding to participant Scott’s invitation

Affirming for Reciprocal Engagement. In addition to invitation, over the course of the focal week of the Make Cycle in 2014, 26 different participants engaged in 281 other types of facilitative moves that made plain the ways coparticipants could engage structures and connect with others. These facilitative moves included sharing or resharing information about synchronous events; recognizing, thanking and/or appreciating others; and publicizing announcements or invitations (see Appendix A).

In 2015, a CLMOOC participant-facilitator Terry made more visible the practices that were being used to extend reciprocity in the community via connection and affirmation. He took screenshots of posts and related comments, using digital annotations such as arrows and comment bubbles, describing what facilitative moves he was seeing in the comments, and noticing when questions were asked and what responses were given, as well as the ways that responses were approached, that is, playfully, empathetically, inquisitively, and so forth.

Based then on this descriptive analysis, he began to shift his annotations into ones that suggested facilitation recommendations, commenting when he noticed responses that seem to build connections between participants and best affirm their engagement. He also highlighted places where connections might have been less effective or altogether missed and even prompted questions about what else might have been done to support participation. Finally, he gathered his own list and linked to lists that others had created that described facilitation strategies, foregrounding the role of affirmation in these practices.

Video 4. Researcher remix of Terry’s documentation of affirmation and reciprocity in CLMOOC.

While CLMOOC participant-facilitators and participants encouraged and invited making and sharing to be a primary means of learning, they acknowledged that the burden of production might be too heavy for some. CLMOOC participant-facilitators resisted establishing primacy for any particular form of participation. They worked to affirm the right to silence, to privacy, and to self-determination in the CLMOOC community, respecting that there might be many good reasons to observe quietly in this public space, noticing the dynamics and textures of this instantiation of open learning, calculating risks, and treading carefully as open can mean open to some individuals and not others.

The facilitative move here both acknowledges the fear of public failure that educators can and do bring with them to open online connected learning communities (West-Puckett, 2017) and helps educators to connect with others who can share learning pathways as well as the burdens of production, distribution, and possible or perceived failure.

In a study of distribution of facilitation in three cMOOC’s, which included CLMOOC network analytics as a case, Gursakal and Bozkurt (2017) likewise found that facilitative moves were widely distributed across CLMOOC, and those — like Terry — who make more facilitative moves (called “gatekeepers” in their study), were catalysts rather than inhibitors for furthering the learning and interaction in CLMOOC. They, too, found affirming engagement for reciprocity to be critical in keeping the learning ecology open and generative:

Gatekeepers’ behaviour in mutual interactions, in other words the degree of reciprocity, determines whether a gatekeeper would be a catalyst or inhibitor in a learning network, which naturally determines the structure of any network, or climate of any learning ecology. (p. 86)

A Case for Infrastructuring

Despite the prevalence of invitational and affirmational moves, in 2015 participant-facilitators were concerned that CLMOOC was failing at the pursuit of educational equity for educators, engaging only those teachers who were already connected to and engaging in open, web-enabled professional development communities. The invitations to make, to play, to share, and to reflect, they feared, spoke to those who were already there, as opposed to those teachers who were either outside or lurking on the fringes of the CLMOOC community. To directly target marginalized educators whom cMOOC facilitators feared lacked “access to specialized, interest-driven and personalized [professional] learning” (Connected Learning Alliance, 2016), participant-facilitators designed the inaugural Make Cycle of 2015 in the form of an invitation that asked participants to unmake an introduction.

Drawing on Ahmed’s (2014) critical analysis of the act of invitation, as well as the growing sentiment expressed in Chachra’s (2015) “Why I’m Not a Maker,” one that characterizes making as a masculinist and commodified activity that precludes feminist methods of nurturing and sharing, Make Cycle participant-facilitators Lacy and Stephanie invited participants to consider the power dynamics inherent in making and in invitations to make:

We see our invitations as already marking particular boundaries and relations, setting us up as hosts or guests, and these are boundaries we’d like to intentionally shatter, unmake, and remake in accordance with the Connected Learning principle of equity and full participation. Could shattering the parameters of our introductions help us to move more quickly beyond “you” and “us” to a space where equity and diversity are hallmarks of a shared ‘we’?

In the introductory newsletter, the participant-facilitators invited educators to participate by disrupting the genre conventions of an introduction, hoping that such a disruption would move others into more visible participation in the community. Lacy and Stephane suspected that perhaps the genre of introductions might have previously functioned as an outing of educators who were or were not part of the connected, digitally savvy in-crowd, despite the invitations and affirmations from past participant-facilitators. To disrupt the power dynamics of “invitation,” educators were encouraged to “smash” their existing understandings of introductions and performances of identity as teachers and learners.

The participant-facilitators suggested a host of tools participants could use to unmake an introduction — or an “untroduction” — including physical and digital photo cutting tools, collaborative Mad Lib generators, digital photo overwriting, manipulation, and glitching, as well as smashing, hacking, and remixing other random physical and digital objects. The artifacts that teachers produced over the week took up that invitation, as some teachers created media that symbolically cast off their professional titles and accolades, created intersectional personal and professional identities, and used playful name generators to create new fictional and discipline-associated introductions, as demonstrated in the remix video in Video 5.

<

Video 5. Researcher remix video containing sections of the introductory newsletter and “untroduction” makes created and shared during the week by multiple participants and participant-facilitators.

Despite the high volume of participation and many CLMOOC participants’ critical engagement with the acts of unmaking introductions, some participants expressed annoyance by what they thought to be an esoteric and impractical 2015 inaugural Make Cycle. For example, in a blog post shared to the G+ community, Sidney, a frequent CLMOOC contributor over the years, mused on the differences between the French and the English meanings of hospitality. She noted that in the English etymology, hospitality lies not in the place but in the “receptive and open-minded” humans who make spaces into places. Sidney was interested in whether or not CLMOOC felt like a place others were comfortable inhabiting; thus, in response to the “Untro” invitation, she designed and shared on the Google+ CLMOOC community an anonymous Google Forms survey to gauge participants’ feelings of comfort.

She discussed the results of the survey in the post. While 58.1% of the 34 respondents reported that they were “easy peasy totally comfortable” participating in the CLMOOC, 41.9% had some level of discomfort. In addition, the survey respondents provided some disparaging comments in response to Sidney’s question, “What is one question you have for or about #CLMOOC?” The more censorious responses included the following:

“I do not see a purpose for the ‘untro’ and feel it is a wasted week. It is too deep, too complex. If you want new invitees to feel comfortable in this space, it had better start in an easy to understand manner…”

“Did anybody think about how this was going to work? …the first make is ridiculous. I thought this was a community mooc, it’s not.”

“When are you going to stop dictating and start involving all of us in designing this?”

In an attempt to invite and channel more diverse participation into the main forums of CLMOOC, it seemed Make Cycle participant-facilitators had perhaps created additional barriers to engagement. In the same blog post, Sidney juxtaposed the participant-facilitators’ invitational moves to the practices of discriminatory design. She wrote,

[Discriminatory design] is design that aims to manage people. Typically, it manages people who those in charge consider a nuisance. Discriminatory design uses barbs or stakes to deter homeless people from sitting, resting, or sleeping. It can also involve constructing different entrances into one building, one for the impoverished and another for the affluent…

Undoubtedly, the organizers of #CLMOOC are not intentionally employing discriminatory design.

However, in any situation where some are intrinsically entitled, like an online course, we should consider the design features that may unknowingly keep people from feeling safe, welcomed, and like they belong there. Similar to a frog in a frying pan on the stove who doesn’t sense that the oil is getting hot until he’s frying, all of us can become so wrapped up in our own experiences that we don’t remember to think about how others may feel.

Are there barbs on our benches that we might not feel?

Sidney’s blog post, including the comments from her survey, invited those issuing the invitations to play the role of guests and ask what might make them more comfortable and more willing to stay and fully inhabit the spaces of CLMOOC. While the Make Cycle participant-facilitators believed themselves to have been critical and reflective about the intended purpose of asking participants to “untroduce” themselves, they were haunted by the survey respondent’s question, “When are you going to stop dictating and start involving all of us in designing this?”

This simple participant query gestured to the too-close-for-comfort associations between “dictating” and “inviting” and invoked Ahmed’s (2014) line of inquiry, “What does it mean, what does it do, for the participation of some to be dependent on an invitation made by others?” By following this rhetoric of invitation, we can begin to understand the limitations of invitation and of participation in open online spaces. Participation is always dependent on the will of others who already inhabit a space, whether they are teachers, facilitators, or mentors. To maintain the contract of hospitality, guests who might be students, participants, or colleagues must behave and continue to behave according to the expectations of the hosts.

Open, then, is never really open. It is framed by the boundaries of expectation and the rhetorics of negotiation between those who organize, arrange, and design the space — in this case, the professional learning opportunity — and those who are allowed to inhabit according to the organization, arrangement, and design of a place.

To more substantially disrupt the power dynamics that exist between participants and participant-facilitators, then, educators might not only rely on the rhetorics of open that function by uncritically deploying the facilitative moves of invitation and affirmation. Instead, as both the anonymous survey respondents and Sidney suggested, designers and facilitators interested in creating spaces and events where others, particularly other educators, want to be and to be part of the professional learning opportunities, might turn to infrastructuring as a relational practice of connecting.

Infrastructuring for Radical Possibility

The findings that follow articulate two infrastructuring moves that surfaced in CLMOOC’s distributed facilitation. These facilitative moves demonstrate the potential of infrastructuring to shift professional learning practices beyond open learning toward connected learning.

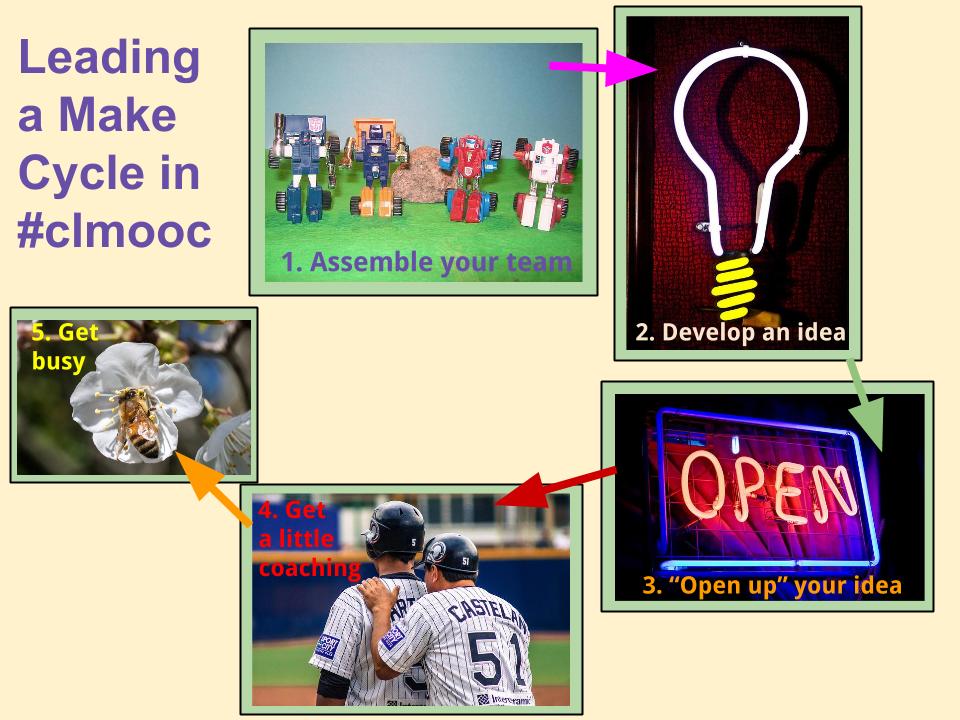

Coaching Toward Imperfection. In 2014 and 2015, Make Cycle teams were supported by CLMOOC participants and previous cycle participant-facilitators through an open-ended process. Make Cycle participant-facilitators were encouraged to “assemble a team, develop an idea, ‘open up’ that idea, get a little coaching, and then to ‘get busy’” on creating invitational newsletters (see Figure 3).

The “get a little coaching” part happened 10 days before a Make Cycle would begin. Coaching sessions were designed to include other educators connected to CLMOOC and were designed to encourage design-thinking and iteration through rapid prototyping and then rapid feedback from other different “user” perspectives.

Imperfect plans were often the preferred mode at CLMOOC, and in fact, this was the overall message conveyed to new Make Cycle participant-facilitators during coaching sessions by those with previous experience. Indicative of the tone of these coaching meetings were two repeated framing notions that experienced participant-facilitators would often share to kick off the design-thinking process. The first was a story — the “Terry and Kevin” story — that retold the experience of two participants, Terry and Kevin, who had taken up facilitative roles in the first CLMOOC Make Cycle.

Terry and Kevin had carefully and meticulously planned a Make Cycle to support CLMOOC participants to introduce themselves via a podcast. They gathered a range of thoughtfully considered resources, shared some examples, and made a few of their own podcasts as potential models. However, their invitation to make introductory podcasts kicked off a cycle of making in which only two podcasts were ultimately made, yet hundreds of educators created other ways to introduce themselves via things that they made. This anecdote, therefore, was meant to highlight the fact that participants found their own ways of working regardless of the specifics of the invitation that was sent to them.

The second framing notion was a mantra and challenge to those taking up facilitating roles: “You can’t break the MOOC! Or can you?” It simultaneously reflected and assuaged the anxiety that most Make Cycle participant-facilitators felt in the early stages of participatory cycle design (i.e., that they will, in fact, produce a prompt, newsletter, or make a facilitative move that would not be taken up or would fall flat with their co-participants — or in one participant-facilitator’s words, “break the MOOC”).

The mantra, and the coaching to repeat the mantra when the participant-facilitator started to feel these concerns, provided an opportunity to let them playfully know that no predetermined perfect facilitative move could be made and that those taking up facilitative roles needed to trust that their coparticipants would continue learning alongside them, that is, they were not alone in infrastructuring the cMOOC. In a reflection regarding her experience being coached in this way, Janelle, described the “ah-ha” she had with this mantra. She explained that instead of exerting her efforts at providing scaffolding and supports — as was typical in her experiences designing curriculum —she needed to intentionally leave the room for others to enter in and make the cycle with her.

Curating Relational Infrastructures. The Find 5 Fridays (#F5F hashtag) in CLMOOC demonstrates a concrete practice of relational infrastructuring that emerged in 2013 and evolved over each year, spinning off into use outside of CLMOOC that continues to the time this paper was written. Deceptively simple, it entailed a way for participants to curate and name a set of makes that had influenced them in some way that week and share them across platforms with the hashtag #F5F.

From 2013, reminders to engage in #F5F were sent out each Friday, inviting participants to find and then share a variety of different types of artifacts from the Make Cycle, including take-aways, conversations, futures, insights, questions, people, commonalities, ah-ha’s, or favorite, influential, meaningful, surprising, fun finds. In addition to finding, participants were invited to “reply, repost, remix, reflect.” In this way, Find Five Fridays were a flexible and malleable structure that engaged participants in the work of literally making connections; that is, creating connective makes to foster further connection with others (people and things) in the community. In the ways that it has been used in CLMOOC, it is a core practice where we see distribution of facilitation as relationship building — through the curation of public lists and reciprocal affirmation through acknowledging the work of others within the community.

As a practice, Find Five Fridays was also remixed and iterated on across the years; for example, in 2013 participant Sheri created an editable Google Slide asking fellow participants to share their favorite #F5Fs, creating a collaborative make. This format was used in each subsequent year. It was not only a textual and visual remix of the invitation to find five on Fridays, but a relational remix, drawing others into her curating activities.

During the focal week of 2014 a participant, Maha, used the #F5F hashtag to share a blog post she had cowritten and posted in another community, titled “Context Matters: View from Around the World.” That piece was structured around five finds (in this case, places) that she and her co-author were suggesting their readers visit.

On her personal blog, she wrote about how the practice of Find 5 Fridays was a way of thinking that she planned on using with students and colleagues alike, resulting in it being was one of the five things she would take with her from CLMOOC. Likewise, participant Traci imagined how she might use this with her future students:

The first week, after writing self-introductions for our first Make Cycle, our #clmooc challenge was to “find five people you’ve never met or five people who have a common interest.” What a perfect way to encourage students to get to know one another! I’ve tried various activities that ask students to read the self-introductions, but this one seems like the most promising one I’ve encountered because it gives students a reason to look for (and I hope build) connections with other.

This seemingly simple practice of recognizing others and their contributions in public ways has played an important role in building the larger relational architecture of CLMOOC. Relational architecture is an emerging field that investigates how media, body, sociality, use, affect, and activity emerge in the imagination and creation of public physical and digital space. The Visual Culture Unit (2012) at the Institute of Art and Design in Vienna explained that relational architecture is concerned with “new spatial practices which move from a hegemonic politics of representation to forms of participation” (para. 1).

These theories of composing, constructing, and inhabiting space-as-relation have been taken up in writing studies and applied to the praxis of imagining and building networked relational spaces for learning, composing, connecting, and remembering in and with the web (Kittle-Autry & Kelly, 2012; Morton-Aiken, 2018;). While relational architecture is a comprehensive strategy for participatory design, following de Certeau (1984), educators might think of relational infrastructuring as less overarching “strategy” and more improvisational “tactic.” Thus, the Find 5 Fridays emerged in-the-making as a tactic that participants used to surface their individual and intersectional, connected learning pathways.

Further Infrastructuring for More Intentional Connection in CLMOOC

The visibility of CLMOOC’s mutability and infrastructuring is still clouded. From the participatory design goals to the facilitative coaching and moves, the ongoing infrastructuring processes of CLMOOC have yet to be intentionally made visible as a practice within the community. Requests for who is in charge, where to look for expectations, and what are assumed norms are quite common and contribute to moments where teachers explicitly seek affirmation and invitation from a hierarchy rather than seeking and providing these moves in side-by-side relations.

Participants in professional learning opportunities designed as events-in-the-making may feel a sense a void in leadership, goals, and outcomes because they are accustomed to hierarchical, teleological models of learning that assume a “sage on the stage.” Intentional, visible infrastucturing is one way to fill that void; however, it must be made plain through facilitative moves that radical, collaborative possibility is the guiding goal and outcome for the professional learning event.

Additionally, in our focal week, we saw only approximately 30 participants out of CLMOOC’s thousands who overtly took up facilitative roles and intentionally made the sort of facilitative moves outlined in this article. Beyond visibility, CLMOOC could engage participants in more actively pursuing open and connection. This engagement would involve intentionally “presenting” (as opposed to “representing,” see Bjögvinsson et al., 2012) CLMOOC as an event-in-the-making.

Surfacing and promoting connective structures among participants, tools, and artifacts would become the focal point of continued design, development, and participation. Through the collaborative act of presenting the event-in-the-making, the hyphens between participant-designer and participant-facilitator dissolve as being a participant in the professional learning opportunity comes to mean engaging as an ongoing designer and facilitator of professional learning. Presenting should also encompass the intentional recruitment of diverse learners and learner interests to afford a wider range of possibility in professional learning collaborations (Junk & Muellert, 1981).

Discussion: Open Revisited

Our analysis of CLMOOC as an open learning experiment suggests that open is a fallacy, one that promotes a vague and amorphous techno-utopianism without addressing the relations of power that enable or restrict participation in communities. In the era of late capitalism, when open education emerges alongside increased educational surveillance, standardization, corporatization, and commodification, open might be another neoliberal rhetoric that assumes unbridled agency and access to resources for all learners.

We, as educational theorists and practitioners, have rarely stopped to consider whose interests are served by open and how open might absolve us from our infrastructuring responsibilities that move beyond open practices of inviting and affirming. Our findings prompt the field to consider the affordances and constraints of “open” and illustrate facilitative practices that engage larger numbers of educators in the negotiation of online professional learning practices, orientations, objects, and spaces.

In educational contexts, the open net is often framed as a toy, a tool, or even an add on, and yet it is also often understood to pose a threat of anarchy or chaos in schools (Losh & Jenkins, 2012). Both of these perceptions should be reconsidered. An alternative is to think of the open net as a set of decisions about humans choose to communicate, compose, and serendipitously connect.

A trusted professional learning environment, in which educators choose to communicate, compose, and connect, is a space in which they can take risks publicly and develop trust through connection. But how to go about ensuring such a space? By shunning an authoritative stance, CLMOOC designed a foundation for openness by cultivating a culture of shared responsibility, collaboration, and a strategically honed ethos of learning alongside. With the ubiquitous messaging of invitation and affirmation, CLMOOC’s goal for open has been to model a critical reconsideration of professional learning in the 21st century. It has generated new learning experiences that push beyond a traditional topdown hierarchical model for extending knowledge by situating educators as 21st-century learners and leaders.

As online spaces and events are imagined and designed as professional learning opportunities, professional development participants-designers have an opportunity to engage new communities of educators. Simply moving professional learning online, however, does little to alleviate offline inequities related to gender, race, and social class (Reich & Ito, 2017; Shah, 2017).

In addition, inequalities related to access and capacity to participate in an open web will only be exacerbated by the recent repeal of Net Neutrality in the US. We have found that when we bring connected learning principles to educators’ professional learning as we did in CLMOOC — learning as interest and production driven, peer-supported and academically oriented — we begin to see how such inequities might be shifted by the infrastructuring strategies and tactics that leave space for emergence and co-construction of the connected learning relational architectures themselves (Seely-Brown, Shah, & Schmidt, 2013). Infrastructuring holds promise to disrupt dominant understandings of professionalism in education — understandings that are all too often remade in the image of bodies from dominant cultural groups (Manthy, 2017) — and in its place, produce a truly coconstructed learning experience.

To foreground communal responsibility and emergence, then, the field might need to leave behind these rhetorics of open in favor of connected, a rhetoric that calls attention to the interrelationships between tools, objects, people, and processes. Though the connected learning framework, at its core, seeks to create more democratic and participatory futures, the participatory strategy in its design principles, particularly its focus on providing openly networked learning opportunities, is a necessary yet insufficient frame to undergird emergence in complex learning ecologies.

We suggest, in its place, an infrastructuring framework for designing learning experiences that are fragmentary and incomplete, made and remade by the variables of dynamic variables of learner interest, the goings together that are mapped through shared passion, inquiry, and purpose, and well as culturally specific practices of meaning-making and relationship-forming. These types of learning opportunities resist easy commodification as they are ever-in-the-making and in-the-unmaking, and they just might offer the radical possibilities of deep professional learning through transformative connection making.

References

Ahmed, S. (2014). Willful subjects. Durham, NC: Duke UP.

Arola, K.L. (2017). Composing as culturing: An American Indian approach to digital ethics. In K. Mills, A. Stornaiuolo, A. Smith & J.Z. Pandya (Eds.), Handbook of writing, literacies and education in digital cultures (pp. 275-284). New York, NY: Routledge.

Bali, M. (2014). MOOC pedagogy: gleaning good practice from existing MOOCs. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 10(1), 44.

Bali, M., Crawford, M., Jessen, R.L., Signorelli, P., & Zamora, M. (2015). What makes a cMOOC community endure? Multiple participant perspectives from diverse MOOCs. Educational Media International, 55(2), 100-115. doi:10.1080/09523987.2015.1053290

Bjögvinsson, E., Ehn, P., & Hillgren, P.E. (2012). Design things and design thinking: Contemporary participatory design challenges. Design Issues, 28(3), 101-116.

Bowen, P. (1987). Open learning formats in high performance training. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 2(2), pp. 29–31. doi: 10.1080/0268051870020206

Bruckman, A. (2002). Studying the amateur artist: A perspective on disguising data collected in human subjects research on the Internet. Ethics of Informational Technologies, 4, 217–231.

Cantrill, C., & Peppler, K. (2016). Connected learning professional development: Production-centered and openly networked teaching communities. In M. Knobel & J. Kalman (Eds.), New literacies and teacher learning: Professional development and the digital turn (New Literacies and Digital Epistemologies). New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing.

Chachra, D. (2015). Why I’m not a maker. The Atlantic Online. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/01/why-i-am-not-a-maker/384767

Chang, B. (2010). Culture as a tool: Facilitating knowledge construction in the context of a learning community. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 29(6), 705–722. doi:10.1080/02601370.2010.523947

Christen-Withey, K. (2014a). Centers and margins: Access and the ethics of openness in the digital humanities. Keynote Address at Computers and Writing Conference, Pullman, WA.

Christen-Withey, K. (2014b). On not looking: Ethics and access in the digital humanities (video). Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/90140105

Connected Learning Alliance. (2016). What is connected learning? Retrieved from https://clalliance.org/why-connected-learning/

Davis, K., Ambrose, A., & Orand, M. (2017). Identity and agency in school and afterschool settings: Investigating digital media’s supporting role. Digital Culture and Education, 9(1), 31-47.

Davis, K., & Fullerton, S. (2016). Connected learning in and after school: Exploring technology’s role in the learning experiences of diverse high school students. The Information Society, 32(2), 98-116.

deCerteau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Farman, J. (2012). Mobile interface theory: Embodied space and locative media. New York, NY: Routledge.

Foote, C. (2013). Making space for makerspaces. Internet @ Schools, 20(4), 26.

Fraiburg, S. (2010). Composition 2.0: Toward a multilingual and multimodal framework. College Composition and Communication 62(1), 100-126.

Glance, D.G., Forsey, M., & Riley, M. (2013). The pedagogical foundations of massive open online courses. First Monday, 18(5). Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.5210/fm.v18i5.4350

Grabill, J.T. (2001). Community literacy programs and the politics of change. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Green, K. (2014). Doing double Dutch methodology: Playing with the practice of participant observer. In D. Paris & M. Winn (Eds.), Humanizing research: Decolonizing qualitative inquiry with youth and communities, (pp. 147- 160). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Gries, L. (2013). Iconographic tracking: A digital research method for visual rhetoric and circulation studies. Computers and Composition, 30(4), 332-348.

Gursakal, N., & Bozkurt, A. (2017). Identifying gatekeepers in online learning networks. World Journal on Educational Technology: Current Issues, 9(2), 75-88.

Ingold, T. (2015). The life of lines. London, UK: Routledge.

Ito, M., Gutierrez, K., Livingstone, S., Penuel, B., Rhodes, J., Salen, K., … & Watkins, S.K. (2013). Connected learning: An agenda for research and design. Irvine, CA: The Digital Media and Learning Research Hub.

Ito, M., Horst, H.A., Bittanti, M., Stephenson, B.H., Lange, P.G., Pascoe, C.J., … & Tripp, L. (2009). Living and learning with new media: Summary of findings from the Digital Youth Project. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where new and old media collide. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Junk, R. & Muellert, N. (1981). Future workshops: How to create desirable futures. Hamburg, GER: Hoffman und Kampe.

Kittle-Autry, M., & Kelly, A. (2012). Introduction to the special issue: Computers & writing 2012, ArchiTEXTure. Enculturation, 14. Retrieved from http://enculturation.net/architexture-introduction

Kolowich, S., & Newman, J. (2013, March). The minds behind the MOOCs. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/The-Professors-Behind-the-MOOC/137905

Lieberman, A., & Friedrich, L.D. (2010). How teachers become leaders: Learning from practice and research. Series on school reform. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Lieberman, A., & Wood, D.R. (2003). Inside the National Writing Project: Connecting network learning and classroom teaching (Vol. 35). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Livingstone, S. (2008). Taking risky opportunities in youthful content creation: Teenagers’ use of social networking sites for intimacy, privacy and self-expression. New Media & Society 10(3): 393–411.

Losh, E. (2017). MOOCs and their afterlives: Experiments in scale and access in higher education. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Losh, E. & Jenkins, H. (2012). Can public education coexist with participatory culture? Knowledge Quest, 41(1) 16-21.

Markham, A.N. (2013). Remix culture, remix methods: Reframing qualitative inquiry for social media contexts. In N. Denzin & M. Giardina (Eds.), Global dimensions of qualitative inquiry (pp. 63-81). Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Markham, A.N. (2017a). Remix as a literacy for future anthropology practice. In J. Salazar, S. Pink, & A. Irving (Eds.), Anthropologies and futures: Researching emerging and uncertain worlds (pp. 225-241). New York, NY: Bloomsbury Press.

Markham, A.N. (2017b). Troubling the concept of data in digital qualitative research. In U. Flick (Ed.), Handbook of qualitative data collection (pp. 511-523). London, UK: Sage.

Manthy, K. (2017). Dress profesh. Retrieved from https://www.katiemanthey.com/dress-profesh.html

Mason, R. (1991). Open learning in the 1990s. Open Learning, 6(1), 49-50. doi: 10.1080/0268051910060109

Morton-Aiken, J. (2018). The compositionist as archivist: Why relational architecture archival practices matter outside the archives (unpublished manuscript).

National School Reform Faculty. (2014). Appreciative inquiry: A protocol to support professional visitation. Retrieved from https://www.nsrfharmony.org/system/files/protocols/appreciative_inquiry_0.pdf

Reich, J., & Ito, M. (2017). From good intentions to real outcomes: Equity by design in learning technologies. Irvine, CA: Digital Media and Learning Research Hub.

Roth, W-M. (2013). To event: Toward a post-constructivist of theorizing and researching the living curriculum as event*-in-the-making. Curriculum Inquiry, 43(3), 388-417.

Saldaña, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Sansing, C. (2014). Your summer of making and connecting. English Journal, 103(5), 81.

Schmier, S. (2014). Popular culture in a digital media studies classroom. Literacy, 48(1), 39-46.

Seely-Brown, J., Shah, N., & Schmidt. P. (2013). Reclaiming open learning: A stake in the ground [Webinar]. In Reclaim Open Learning Symposium. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RhlwvdNgYEo

Selber, S.A. (2004). Reimagining the functional side of computer literacy. College Composition and Communication, 55, 470–503.

Shah, N. (2017). Putting the ‘C’ in MOOC: Of crises, critique, and criticality in higher education. In L. Losh (Ed.), MOOCs and their afterlives: Experiments in scale and access in higher education. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Siemens, G. (2012, July 25). MOOCs are really a platform. Elearnspace: Learning, Networks, Knowledge, Technology, Community [blog]. Retrieved from http://www.elearnspace.org/blog/2012/07/25/moocs-are-really-a-platform/

Siemens, G. (2013). Massive open online courses: Innovation in education. In R. McGreal (Ed.), Open Educational resources: Innovation, research and practice. Retrieved from https://oerknowledgecloud.org/sites/oerknowledgecloud.org/files/pub_PS_OER-IRP_CH1.pdf

Slusher, B. (2009). Praising, questioning, wishing: An approach to responding to writing. E-Voice, 2(1). Retrieved from https://www.nwp.org/cs/public/print/resource/2868

Smith, A., Dillon, J., & Zamora, M. (2017). Connectivist massive open online courses. In K. Peppler (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of out-of-school learning (pp. 136-140). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Smith, A., West-Puckett, S., Cantrill, C., & Zamora, M. (2016). Remix as professional learning: Educators’ iterative literacy practice in CLMOOC. Education Sciences, 6(12), 1-19.

Spinuzzi, C. (2005). The methodology of participatory design. Technical Communication, 52(2), 163-174.

Stornaiuolo, A., & Hall, M. (2014). Tracing resonance. In G. B. Gudmundsdottir & K. B. Vasbø (Eds.), Methodological challenges when exploring digital learning spaces in education (pp. 29-43). Boston, MA: Sense Publishers.

Stornaiuolo, A., Smith, A., & Phillips, N.C. (2017). Developing a transliteracies framework for a connected world. Journal of Literacy Research, 49(1), 68-91.

Thomas, D., & Brown, J.S. (2011). A new culture of learning: Cultivating the imagination for a world of constant change (Vol. 219). Lexington, KY: CreateSpace.

Visual Culture Unit. (2012). Relational architecture. University of Vienna. Retrieved from https://institute.tuwien.ac.at/visual_culture_unit/research/relational_architecture/EN/

Weller, M. (2014a). The battle for open: How openness won and why it doesn’t feel like victory. London, UK: Ubiquity Press.

Weller, M. (2014b). The battle for open. The Open University on Youtube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ODL-owGjti8

West-Puckett, S.J. (2017). Materializing makerspaces: Queerly composing space, time, and (what) matters (Doctoral Dissertation, East Carolina University). Retrieved from The ScholarShip: http://hdl.handle.net/10342/6344

West-Puckett, S.J. & Banks, W.P. (2014). Uncommon connections: How building a grass-roots curriculum helped reframe common core state standards for teachers and students in a high-need public high school. In R. McClure & J. Purdy (Eds.), The next digital scholar: A fresh approach to common core state standards in research and writing (pp. 353-381). Medford, NJ: Information Today, Inc.

West-Puckett, S.J., Flinchbaugh, K., & Herrmann, M. (2015). Knotworking with the National Writing Project: A method for professionalizing contingent faculty. In L. Guglielmo & L.L. Gaillet (Eds.), Contingent faculty publishing in community (pp. 35-55). London, UK: Palgrave Pivot.

Wohlwend, K.E., Buchholz, B.A., & Medina, C. (2017). Playful literacies and practices of making in children’s imaginaries. In K. Mills, A. Stornaiuolo, A. Smith, & J.Z. Pandya (Eds.), Handbook of writing, literacies and education in digital cultures (pp. 136-147). New York, NY: Routledge.

Worth, J. (2015). Nishant Shah: Privacy and trust in open education part 1. Speakly Opening. Disruptive Media Learning Lab. Available: http://speakingopenly.co.uk/

Zamora, M. (2017). Re-imagining learning: CLMOOC and the transformative power of open. In L. Losh (Ed.) MOOCs and their afterlives: Experiments in scale and access in higher education. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Appendix A

Facilitative Move Codes

![]()