Given the diverse social milieu of the world in which teachers live and work, as well as the predominantly White, female, and middle class population of preservice teachers (PSTs; Boser, 2014), preparing PSTs to enter the profession equipped with the skills and tools to work toward a more equitable society is increasingly important. Privileged positionality, and the fact that teacher education programs frequently avoid promoting these critical conversations in favor of remaining firmly on the safer terrain of lesson planning (e.g, see Britzman, 2003), result in many PSTs lacking extensive experience engaging in discussion around oppressive phenomena such as racism, classism, regionalism, homophobia, and the many intersections therein (Ladson-Billings, 1999; McIntyre, 2002).

Hooks (1994) asserted that engaging in a professional dialog “is one of the simplest ways we can begin as teachers, scholars, and critical thinkers to cross boundaries, the barriers that may or may not be erected by race, gender, class, professional standing, and a host of other differences” (p. 130). In order to engage these issues meaningfully, PSTs require spaces and opportunities to develop and articulate their own positionalities toward issues of social justice. Providing spaces to foster these conversations is essential in the effort to encourage PSTs’ growth as social justice practitioners.

To that end, we designed a study to examine the extent to which pairing microblogging with the content of a young adult literature (YAL) course helped students develop their social consciousness as well as better understand, articulate, and expand their own positionalities toward the injustices about which they read (i.e., racism, sexuality, regionalism, etc.). As they tweeted, PSTs were asked to follow two guidelines: (a) strive to develop and articulate their own stances toward social inequities, and (b) consider ways in which they might engage these issues of (in)equity in their own classrooms.

We found that while the practice of microblogging afforded students certain benefits, the platform was largely incompatible with authentically engaging issues of social justice. PSTs struggled to move away from the traditional roles and spaces of classroom dialog and to develop new voices and stances through a social media platform.

Likewise, PSTs found extending their in-class conversations to Twitter to be difficult—that is, they struggled to navigate the spaces between their physical classroom and the online world of the microblogging platform. Finally, PSTs experienced difficulty negotiating Twitter’s social dimensions; they struggled to share their developing, intimate ideas of social justice using the online microblogging space.

After hypothesizing the causes for the seeming dialogic mismatch between PSTs, microblogging, and their ability to question, articulate, and otherwise develop their positionalities in this paper, we suggest that teacher educators interested in using Twitter to promote the critical analysis of social justice issues should utilize microblogging as but one of many instructional tools in a comprehensive, guided approach.

Defining Terms

For the purposes of this paper, we conceptualize dialogic spaces as both in-person and online domains that house, foster, and facilitate critical conversations around a variety of sociopolitical issues. The shape-shifting qualities of these dialogic spaces hold with the theoretical underpinnings of hybrid pedagogy (Stommel, 2012), which sees learning as a process that occurs in both physical and virtual learning forums.

Maher and Tetrault (1994) noted that “the concept of positionality points to the contextual and relational factors as crucial for defining not only our identities but also our knowledge as teachers and teacher educators and students in any given situation” (p. 165). Articulating a positionality demands that individuals take a self-reflexive approach in examining their own identities, beliefs, and stances. Additionally, it requires that individuals consider their own position, particularly when speaking, and how various positionalities relate to and complicate one another (Haritaworn, 2008).

Under ideal circumstances, the teacher educator creates disequilibrium (Rich, 1980) in students’ positionalities so that they may better understand the systems of privilege from which they often benefit, and most importantly, how to use their classrooms as spaces in which to push back against these oppressive forces (Martin & Van Gunten, 2002).

Social justice is a phrase laden with a complex history (e.g., see Miller, 1999); the term has been articulated, interpreted, and assessed in a myriad of ways (Alsup & Miller, 2014; North, 2006). For our part, like Bell (1997), we conceptualize social justice as both a goal and process that promotes the “full and equal participation of all groups in a society that is mutually shaped to meet their needs’’ (p. 3).

This collaborative work relies on a sustained commitment from all people–that is, those people belonging to both nondominant and dominant groups. Actualizing social justice education authentically and with fidelity first depends on understanding America to be a stratified society that has long granted certain rights, properties, and opportunities to the social elite.

We hold with Hackman’s (2005) belief that social justice education should engender student empowerment, promote equitable distribution of resources and social responsibility, and provide students with an opportunity to analyze systems of power. Tantamount to this work is a commitment to taking action against these hegemonic forces in order to disrupt the inequitable educational and social milieu. In short, social justice work is an orientation—a way of being in the world (Golden & Christenson, 2008).

Diversity and fairness are frequently—and erroneously—presented as entities analogous with social justice (Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2012), notions that are at odds with the original intent behind the phrase (Hackman, 2005; Hayes & Juarez, 2012). Teacher education programs share the culpability for these inaccurate depictions, given that many programs prefer a color-blind approach to teaching (Cochran-Smith, 2020) and work to cultivate and maintain a “culture of niceness” (McIntyre, 2002, p. 44) that silences critical conversation and critique in many colleges and universities.

Alsup and Miller (2014) cautioned that Standard VI—the long fought-for and contested social justice strand approved by the National Council of Teachers of English and the National Council of the Accreditation of Teacher Education in 2012—has been interpreted and assessed in ways incongruent with the aims of authentically enacted social justice. Consequently, teachers enter into the workforce largely unprepared to teach their culturally and linguistically diverse students justice (Bell, 2002; Sleeter, 2012); that their classroom practices frequently only further marginalize those students already positioned on the classroom peripheral thwarts the equity-driven aims of social justice.

Thus, teacher educators must offer generative ways to better prepare their PSTs to work as change agents in their classrooms and carefully examine the successes and failures of these pedagogies. Here, we describe our approach to preparing PSTs for social justice work, a study situated in the conversations around social justice teacher education and the possibilities of Twitter as a viable dialogic format for educators.

Review of the Literature

Scholars have long pointed to the importance of teacher educators creating opportunities for PSTs to develop critically oriented social positions and stances (Gay & Howard, 2000; Gay & Kirkland, 2003; Villegas, 2007; Whipp, 2013). Teacher educators are called to use their classrooms as spaces in which to support PSTs as they work to understand, engage, and address social justice issues (Cochran-Smith, 2008). In reviewing the literature, we aimed to understand the conversations around YAL, microblogging, and social justice teacher preparation and the points of concurrent discussion reflected in the scholarship.

One such way teacher educators buttress the efforts of social-justice-oriented teacher education is through teaching YAL, which provides PSTs with a means by which to grapple with complex sociopolitical issues and consider how they will engage these matters in their own classrooms (Glasgow, 2001; Hayn, Kaplan, & Nolen, 2011; Singer & Shagoury, 2006; Wolk, 2009).

Bull (2011) suggested that using YAL with PSTs can assist in developing the critical thinking necessary to engage in meaningful analysis of texts and of the world, both in and outside the classroom, and ultimately foster those skills in their future students. More recently, Boyd and Pennell (2015) explored the many ways in which YAL can be read using critical theory in order to engage PSTs in discussions around inequity and oppression.

Like YAL, Twitter has also proven beneficial when applied in educational contexts (Gerstein, 2011; Grosseck & Holotescu, 2008). In a study of in-service English teachers, Rodesiler and Pace (2015) found that engaging in professionally oriented participation using Twitter deepened teachers’ practice, increased their capacity to support students, alerted them to new resources and ideas, provided them with an opportunity to assume new leadership roles, and allowed them to extend their thinking by owning a particular specialty, such as writing or YAL.

Forte, Humphreys, and Park (2012) wrote that Twitter provided teachers with a space to create and maintain professional relationships with community members, which in turn, allowed them to gain new practices to take back to their classrooms. The same study found that Twitter provided a space for teachers to share resources and information.

Gerstein (2011) posited that Twitter holds promise for teachers’ engaging in multimodal and engaging professional development. Twitter also provides a way for teachers to model successful pedagogies tailored to their students’ needs (Grosseck & Holotescu, 2008).

In the university classroom, Twitter has been shown to improve class participation and feedback, collaboration, social presence, ambient awareness, classroom community, literacy, and critical stance (McCool, 2011). In a cross-university study, Farwell and Waters (2011) paired students from their respective courses with the intent of having students learn to communicate within Twitter’s 140 character limit, develop online social etiquette, and build relationships. While students initially expressed disdain at the assignment, ultimately, they reported that the practice was meaningful and that the social platform had pedagogical merit.

Twitter has also been used to engage university students in discussions of current events (Jaworowski, 2010). Twitter allows professors and students to gather, aggregate, and disseminate information quickly, both asynchronously and when outside the traditional classroom meeting times (Jaworowski, 2010; McCool, 2011), an appealing attribute given the time constraints professors often navigate.

In the teacher education classroom, microblogging has proven an effective instructional practice as it opens up new occasions for critical discussions and analysis of course materials and society. In a 2013 study, Kim and Cavas (2013) analyzed PSTs’ Twitter contributions, using these tallies to define PSTs as “contributors,” “advisors,” “audiences,” and “silent participants” in their community of practice. They found that interacting on Twitter established students’ legitimacy, which the authors defined as gaining peer credibility, enlarging divisions of labor in a social environment, collecting reinforcement from colleague teachers in the progress model of collaborative reflection, increasing social recognition, and exhibiting leadership.

Nicholson and Galguera (2013) found that microblogging moved students beyond passive participation and encouraged them to function as active creators of information. Wright (2010) examined the use of Twitter to promote reflection in PSTs and found that students, through support and sense of community, were able to develop stronger reflective skills. Krugger-Ross, Waters, and Farwell (2013) found that, though privacy, interaction, and workload issues arose when they asked their PSTs to use Twitter, the platform also deepened connections and engagement with course materials and concepts.

Van Manen (2010) posited that using social media classifies as a phenomenological exercise, given that participating in social media often brings out and concretizes one’s innermost beliefs. She questioned, “In what ways can…the Hidden remain a possibility in our increasingly technological and digital world?” (p. 8). Here, we asked students to acknowledge and explore “the Hidden” specific to each of them—a notion inextricably bound to positionality—in order to reflect critically on how these beliefs might shape their ability and willingness to engage social-justice-oriented work in their own classrooms.

Little scholarship has examined the ways in which microblogging platforms such as Twitter may serve as a dialogic space in which PSTs can develop their own positionalities toward pertinent sociopolitical matters. This study aims to fill this void. Engaging YAL and discussing its nuanced, timely issues served as a catalyst for PSTs’ tweets. In conducting our analysis, we examined the extent to which this space provided a successful forum for PSTs as they began to develop and articulate their own positionalities.

Theoretical Framework

We created our theoretical framework from three different elements to account for students’ experiences with both YAL and the dialog associated with social justice issues. First, we borrowed from Rosenblatt’s (1938) transactional theory (she argued that reading is an interaction between reader and text) in order to understand and give importance to the relationships fostered between PSTs and the YAL they read. A vital component of this study involved PSTs’ establishing personal connections with the texts and characters of the YAL novels. These personal connections, through characters and about the social issues they represented, served as the potential basis for students developing social positionalities.

Second, we used social constructivism (Wells, 1999) as a lens for examining students’ working collaboratively to create classroom artifacts (i.e., classroom discussions and Twitter dialog), as well as the resulting learning and growth. The inclusion of Twitter with YAL allowed students to extend the conversations traditionally limited to the classroom by opening up dialogic spaces (via microblogging) and opportunities to work together to discuss the social issues they encountered through the novels and to develop their own social stances and voices.

We overlayed both of these frameworks with Stommel’s (2012) theory of hybrid pedagogy to support and guide our work. Stommel offered the following distinction of hybrid pedagogy, which he separated from the related concept of blended learning:

At its most basic level, the term “hybrid”…refers to learning that happens both in a classroom (or other physical space) and online. In this respect, hybrid does overlap with another concept that is often used synonymously: blended. Blended learning describes a process or practice; hybrid pedagogy is a methodological approach that helps define a series of varied processes and practices. (Blended learning is tactical, whereas hybrid pedagogy is strategic.) When people talk about “blended learning,” they are usually referring to the place where learning happens, a combination of the classroom and online. The word “hybrid” has deeper resonances, suggesting not just that the place of learning is changed but that a hybrid pedagogy fundamentally rethinks our conception of place. (para. 7)

This reconceptualized notion of place, which we frequently refer to as “space,” allowed us to make sense of the ways in which microblogging outside of the classroom supported students’ efforts to develop and hone their social justice positionalities. Like Stommel, we hold that the multiple intersections that mark hybrid pedagogy (including the intersections of Physical Learning Space/Virtual Learning Space, On-ground Classrooms/Online Classrooms, Use of Tools/Critical Engagement with Tools, and Teaching and Learning/Critical Pedagogy) provide for a more insightful understanding of how this work challenged traditional approaches to English teacher preparation.

Methods

Because of the paucity of research around using Twitter for social justice purposes in the preservice teacher education classroom, our ultimate goal in designing this study was to generate grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006). We based our choice to use the forum of Twitter on a variety of factors, one being its popularity among college-aged students. A 2014 study found that 23% of the U.S. adult population used Twitter; the website is most popular among adults belonging to the 18-29 demographic (Duggan, Ellison, Lampe, Lenhart, & Madden, 2014).

Given these realities, we conjectured that allowing PSTs to engage a platform with which many of them were already familiar would entice them to share their own emerging positionalities as they grappled with various matters of social justice discussed during the course. To that end, two research questions drove this study and served as a lens for analyzing the data:

- In what ways do preservice teachers use Twitter to extend their in-class discussions of social justice issues?

- What affordances and constraints exist for Twitter as a dialogic space for preservice teachers to develop and articulate social justice positionalities?

Context of the Study—The Course

A requirement for English education majors, this course serves as an introduction to YAL and the pedagogical implications for its application in English language arts classrooms. The primary objective of this course was twofold: to benefit both the PSTs and their future students. One of our goals was to help PSTs engage in discussion of the stereotypes, assumptions, and social justice issues that arise in YAL in order to help them more effectively implement these and similar novels in their own future classrooms and to assist their own future students.

A second and related goal was to engage PSTs in meaningful analysis of the world around them in order to help their own students analyze and wrestle with the issues relevant to their lives. An additional goal was to assist PSTs with critically analyzing their own positionalities and to use those experiences to help their future students do the same.

To transfer class discussion to the microblogging space, PSTs were asked to adhere to two parameters: (a) to articulate their own positions and stances toward the social inequities that played out in the readings and (b) to use those reading experiences to consider ways in which classroom teachers, in both their personal spheres and classrooms, could promote a more equitable social and educational milieu. The assignment description students received read as follows:

Your goal for this assignment is to use Twitter to extend our in-class conversations and engage in ongoing conversations about our books and the topics that accompany them. Using our hashtag, you will post throughout the week (aim for 2-3 original tweets and 2-3 responses per week). Throughout the semester, I would like you to utilize a non-traditional space for academic discussion to engage in meaningful discourse around the powerful topics of social justice that emerge from your reading.

Students tweeted before, while, and after they read each novel. Rather than simply acting as a reader, the instructor (first author Cook) became an active participant in the Twitter dialog with an intentional goal of modeling socially conscious posting and responses. The instructor tweeted often and for a variety of purposes: to spark conversation, to ask guiding questions, to validate and encourage deep thought, and to model positionality development and articulation. The purpose of this strategy was to scaffold PSTs as they attempted to develop new ways of thinking and sharing by making the shift to a new dialogic space, especially one where concise writing is mandatory (e.g., 140 characters maximum).

We carefully considered the findings revealed to us by the literature review and applied this knowledge to the assignment’s design. We knew that Twitter had the potential to help PSTs develop and hone their reflective skills (Wright, 2010), mature into a reflective professional community (Kim & Cavas, 2013), and see themselves as generators of information (Nicholson & Galguera, 2013); thus, we surmised that this exercise would be a meaningful opportunity for students to expand their social consciousness, particularly with regard to the way this awareness would impact their work as secondary English teachers.

We were also aware that issues of privacy might arise (Krugger-Ross et al., 2013), as well as concern over sharing their innermost musings (Van Manen, 2010). To attend to these concerns, we first shared Stommel’s (n.d.) “Getting Started with Twitter” with the PSTs. This document, which instructs students on how to create an account, defines important terms such as retweeting and hashtags, and provides links on using Twitter in the classroom, proved particularly helpful for students who had limited or no experience tweeting prior to the course.

The instructor explained to students that many contribution types are available (as in Krugger-Ross et al., 2013), and that an array of comment types would be ideal. While we wanted students to be bold and critical in their exploration and discussion of social justice issues, it was important to advise students not to share any insight they felt uncomfortable disseminating publically.

While reading each book, the instructor facilitated classroom conversations about the ways in which certain issues, such as racism, classism, and homophobia, were manifested through the characters and about student responses to and positions on these issues. See Table 1 for a list of novels used in the course, summaries of those novels, and a list of the social justice issues identified in each text.

Table 1

YA Novels and Social Justice Issues

| YA Novels | Summary | Social Justice Issue(s) |

| Monster, Walter Dean Myers | A narrative written as a screenplay that asks readers to serve as active jurors in the murder trial of a teen | ·Assumptions/stereotypes of African American males |

| American Born Chinese, Gene Luen Yang | Three narratives woven together—a traditional Chinese myth, the story of an Asian American adolescent, and an alter-ego representing a skewed self-perspective | ·Assumptions/stereotypes of Asian and Asian American stereotypes ·Misunderstanding of the immigrant experience ·Assumptions/stereotypes of American identity |

| My Most Excellent Year, Steven Kluger | Alternating narratives of three diverse high school freshmen in Boston | ·Assumptions/stereotypes of homosexuality ·Assumptions/stereotypes of Hispanic females ·Assumptions/stereotypes of children with disabilities |

| Shine, Lauren Myracle | A narrative, centered around a local tragedy, that requires readers to examine a variety of stereotypes engrained in the rural south | ·Assumptions/stereotypes of homosexuality ·Assumptions/stereotypes of drug abuse ·Assumptions/stereotypes of rural southern life |

| The First Part Last, Angela Johnson | An alternating (present/past) narrative describing a teen couple’s pregnancy and the birth of their child | ·Assumptions/stereotypes of teen parenthood ·Assumptions/stereotypes of gender roles ·Assumptions/stereotypes of African American teens |

| The Last Summer of the Death Warriors, Francisco X. Stork | An alternating narrative of two teen males, one bent on revenge and one dying of cancer, bond over their search for truth and meaning in life | ·Assumptions/stereotypes of Hispanic males ·Assumptions/stereotypes of cancer and cancer patients |

| Will Grayson, Will Grayson, John Green and David Levithan | An alternating narrative from the points of view of two teens who share the same name and struggle with their search for identity and acceptance | ·Assumptions/stereotypes of homosexuality |

| We Were Here, Matt de la Pena | A narrative of a biracial young man who struggles to come to terms with his identity and his role in his brother’s death | ·Assumptions/stereotypes of race ·Assumptions/stereotypes of being biracial ·Assumptions/stereotypes of Hispanic and African American males |

| The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, Sherman Alexie | A narrative of a young Native American with one foot in two worlds (the reservation and beyond), who searches for an identity, a purpose, and a place to fit in | ·Assumptions/stereotypes of Native Americans ·Assumptions/stereotypes of race and ethnicity |

| Wintergirls, Laurie Halse Anderson | A narrative of an anorexic teen, whose former best friend is found dead, struggling to keep her out of control life in order | ·Assumptions/stereotypes of eating disorders ·Assumptions/stereotypes of societal expectations |

| Hole in My Life, Jack Gantos | A true narrative of a teen who dreams of becoming a writer but finds himself surrounded by drugs and on his way to prison | ·Assumptions/stereotypes of drug use ·Assumptions/stereotypes of those labeled “criminals” ·Assumptions/stereotypes of racial unrest |

| Mexican Whiteboy, Matt de la Pena | A narrative of a biracial teenage boy struggling to find his identity between being white and being Mexican | ·Assumptions/stereotypes of biracial issues and identity ·Assumptions/stereotypes of drug and violence stereotypes ·Assumptions/stereotypes of race |

Between class meetings, students were asked to extend their classroom conversations by (a) transferring discussions of the social justice issues to the online space of Twitter and (b) expanding their critical lenses and perspectives away from the books and toward the world in which they live. To archive classroom conversations, following every class meeting, the instructor wrote a summary of the topics and conversations from that day.

A course hashtag was used to archive all tweets and to provide students with a more organized space to read, consider, and respond to the posts of their peers. This archived data allowed for students also to return to older/previous posts after taking time to consider and reflect; it also allowed for easy data collection for the purposes of this study. At the conclusion of the semester, course evaluations were also collected from all students.

In an effort to provide students with the tools necessary to move these conversations successfully outside the classroom, students regularly received discussion prompts, guiding questions, and examples of multiple points of view to mull over and use to guide their own contributions to in-class discussions. Moreover, the instructor was an active participant in all class discussions both to further student learning and provide students with models of critical thought and engagement in discussions surrounding social justice issues.

The discussion prompts used were intended to be in-class conversation starters and to serve as models of the types of questions the instructor wanted students to wrestle with themselves and to discuss with their classmates. To begin the first class meeting after reading the novel My Most Excellent Year (Kluger, 2008), for example, students were asked, “How are issues of homosexuality portrayed in the novel, and are these portrayals positive or negative? Does it vary by character/situation? In what ways do these portrayals parallel our society?”

When the Twitter conversation stalled on Lauren Myracle’s ( 2011) novel, Shine, students were guided with the question, “How does Shine make you reevaluate your own beliefs, stereotypes, and truths?” During the same discussion, students were again prompted with, “We can probably take several things away from the setting she chose, beyond the obvious prejudices. Thoughts?” Students were provided similar discussion prompts to all the novels and social justice issues discussed throughout the semester.

Similarly, guiding questions and comments were utilized often for a variety of reasons: refocusing student discussions, expanding the topics and perspectives students discussed, and prompting new thought. For example, the instructor often shared links to articles on using Twitter in classrooms, as well as articles about the novels and issues being discussed. Guiding comments were also provided to acknowledge a good example of a Twitter post and elicit responses from other class members. Additionally, these guiding comments were designed to elicit additional discussion: “We’re seeing a range of comments and emotional responses to the novel so far. Keep them coming and let’s make some sense of the text.”

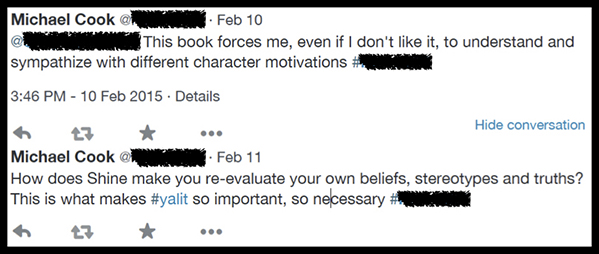

Last, the instructor posted examples of a variety of points of view to model for and guide students in their tweets. Examples can be seen in two tweets from the instructor (see Figure 1).

Another example of the instructor’s use of posts to model online conversations was seen in response to a student tweet sharing her negative reaction to a situation in the novel Shine: “Well written books should elicit emotional responses, even if that response is negative. I’d like to hear more.” A final example was in response to students debating whether one view or another (from two different novels) of homosexuals was accurate: “Is it beneficial to use both books with both views to help create their own ‘real’?”

Data Sources

Participants in this study (n = 20) were PSTs in an undergraduate course on YAL at a small comprehensive university in the midwestern United States. The course encompassed a range of students (see Table 2) at varying stages of their teacher preparation programs. All participants in the course were full-time students; however, one was a nontraditional student in that she had returned to school after taking 5 years off after high school to work and care for her children.

Table 2

Demographic Information

| Year | Race | Gender | |||

| Freshman | 0 | African American | 5 | Male | 6 |

| Sophomore | 12 | Asian American | 1 | Female | 14 |

| Junior | 4 | White | 14 | ||

| Senior | 4 | ||||

Data sources for this study included classroom dialogs and interactions, Twitter posts (n = 1,003) and course evaluations. Classroom dialog data took two forms: (a) instructor notes during class, where student statements made during class discussions could be accurately transcribed and (b) summaries written after each course meeting.

During class discussions, the instructor transcribed student comments. Immediately following each session, the instructor also composed a summary of the class conversations. All tweets were collected using a common course hashtag, which allowed for posts to be archived and easily accessed. Additionally, all 20 students completed course evaluations, which included questions about their perceptions of, uses for, and learning from the ongoing Twitter conversations. These multiple data sources were incorporated to provide a layered description of how students participated in and responded to this dialogic space, particularly as they grappled with the complex themes of racism, sexuality, classism, stereotypes, and all the intersectionalities therein.

A case study design was selected so that we might better understand in what ways pairing microblogging with YAL served as a successful platform for PSTs as they discussed and developed their own social consciousness. Thomas (2011) defined case studies as holistic analyses of individuals, groups, systems, and phenomenon. As such, case study methodology was use to examine one specific class of PSTs (in one setting and in one semester) in order to illuminate their experiences within the context of their course. This inquiry process allowed us to make sense of the nuances of one particular class of PSTs and use this understanding to make sense of PSTs’ experiences generally (as asserted in Creswell, 2009). Furthermore, this methodology allowed us to account for contextual factors associated with the class and to make meaning from the situation and experience.

Limitations

Three limitations to this study are relevant. First, we did not explicitly examine or discuss whether students were concerned with a larger, more public audience seeing their posts—that is, the degree to which students were under the influence of and intimidated by the public sphere of Twitter. However, the data suggest that some students were aware of the differences in dialogic spaces and were at times cognizant of who was watching (i.e., their audience), although these concerns were often associated with whether or not the audience was synchronously or asynchronously engaged.

The second limitation of this study involves an absence of PSTs’ reflections on their personal growth as social-justice-oriented practitioners. During the study, we did not ask students to self-assess the development of their social justice positionalities. As such, our data do not provide a view into any disparity between PSTs’ claims about using Twitter to develop social justice positionalities and their actual doing so. We did, however, focus our inquiry on making sense of students’ explicitly articulated stances, which we interrogated using inductive analysis.

A third limitation worth noting involves PSTs’ Twitter accounts: how long they had them, how they utilized them, how their experiences in-class were related to or disparate from their personal uses. We did not gather information on students’ Twitter accounts or how they used Twitter prior to this course; however, an informal assessment during class conversation revealed that most of the PSTs had a Twitter account, and those who did not were at least familiar with the platform.

Data Analysis

In keeping with our aim of generating grounded theory, we employed Thomas’s (2006) approach to inductive analysis by openly coding all collected data (class discussion notes, tweets, and course evaluations). To begin, we summarized all data, linking the data with the purpose of the study and then using these links to establish a framework by which to analyze our data. To guide our analysis, we employed analytic memo writing (Charmaz, 2000) to ensure salient details and themes were captured and represented during the entirety of the coding process.

Codes were refined until theoretical codes emerged. We employed a constant comparative method throughout our analysis, revising and recoding the themes as we considered incidents in relation to those previously recorded both within and among the different thematic designations (as in Glaser & Strauss, 1967).

Throughout data collection, we engaged in regular write-ups to flesh out the codes that emerged and to summarize our findings. We wrote memos (see Figure 2 for samples) once per week (i.e., once per novel). At the conclusion of the study, we used these memos to guide our discussion of the findings. While working toward axial codes, we coded 5% of the data together to ensure interrater reliability (Cohen, 1968).

| Example 1 “Student tweets this week were largely surface-level. Rather than discussing the concepts of racism and stereotyping found in American Born Chinese, they instead shared their opinions on the graphic format of the text and graphic novels in general. For example, while one student noted that she found the graphic novel interesting, one of her classmates shared the educational benefits she perceived graphic novels to have.” Example 2 “This week, students discussed and tweeted about My Most Excellent Year. Many student tweets were able to make personal connections to the issue of homosexuality, citing that man of their classmates and friends were gay. Additionally, some made connections to their major (e.g., theater) and our university (stating an emphasis on performing arts). Overall, the student tweets contained far fewer critical discussions of the issues of social justice than our in-class conversations. During class, students more openly talked about sexuality and race, both within the context of the novel and within our society. Online, they made personal connections to positive aspects but rarely mentioned more negative realities and perceptions.” |

| Figure 2. Sample analytic memos. |

Our understanding of transactional theory resulted in our treating all in-class and online reactions to the YAL novels as an individual exchange specific to each student. Second, we recognized that both the in-class and online discussions provided opportunities for students to learn from, question, and craft meaning from and with each other, interactions that enriched the class and motivated students to explicate, develop, and consider their social justice positionalities.

Our sense of hybrid pedagogy presented a means through which to synthesize all of these arguments as we considered the ways in which these entities—face-to-face and virtual spaces, as well as passive and experiential learning, among other seemingly dichotomous notions—allowed for a bending of the traditional classroom learning space and sense of dialogism.

Findings

According to our findings students perceived that using Twitter afforded certain benefits, including providing an accessible conduit through which to share ideas, a means to extend and deepen in-class conversations, and a way to improve their conciseness given the 140-character limit. They simultaneously experienced difficulty extending the rich qualities of in-class conversations and, likewise, struggled to negotiate the social dimensions of Twitter.

Dialogic Aspects of Twitter

The first theme that emerged from the data was that of the dialogic aspects of Twitter—students’ uses of microblogging as a dialogic tool. Within this theme, the PSTs noted three distinct benefits: students and audience, student comfort, and student interest.

Students and audience. Many students enjoyed dialoging with an expanded audience. They also appreciated the ability to return continuously to the archived Twitter conversations. Discussing audience, one student said, “It was good to get responses from a broader group of people (more than just those in our class).” Another stated that Twitter “has helped me to interact with others in a professional manner about real topics.”

In a classroom setting, students respond to their classmates and their instructor. In a microblogging format such as Twitter, students receive responses from all those in their social network (i.e., those following them on Twitter). Additionally, if a comment is retweeted or quoted, the pool of potential responders grows exponentially. Discussing this online space, these students noted a benefit from receiving responses to their posts from a social (not classroom) audience as well. This activity helped them to consider more fully how they phrased posts, and the expanded feedback allowed them to consider more fully the stances and views they developed throughout the semester.

A third student echoed this sentiment and noted the “larger audience” required more thought before posting. Archived conversations (via a course hashtag) proved helpful as well. In her course evaluation, one student wrote, “Even when I don’t contribute to the back channel, I can consider what others are thinking and posting and consider those against my own thoughts,” suggesting a benefit from simply reading posts.

Student comfort. Students also perceived benefits of using Twitter to engage and discuss issues of social justice, even though many of the online posts lacked the depth and social engagement of the in-class discussions. One student said, “I think it has added to our experience….I think it just put me outside my comfort zone.” Another student noted that the use of Twitter added to personal learning, “because it was an easier opportunity to share ideas than it is in class, when we sometimes need time to think through how we feel about something before we share.”

Still other students went on to explain how Twitter empowered them to participate in ways they felt unable to do during in class discussions pertaining to complex social justice issues. In the course evaluation, a student reflected that “it can be tough to share our opinions on difficult topics in front of everyone.” A classmate shared a similar concern in his evaluation: “I felt more comfortable sharing sensitive ideas when I wasn’t in the classroom, in front of everyone.” Here, students believed Twitter provided a way to share thoughts and beliefs outside the traditional face-to-face setting. Students felt the microblogging tool provided them a layer of buffering, helping them to approach the discussions and topics they usually avoided.

Another student found that the use of Twitter made him more comfortable sharing his views and stances on social justice issues once he saw that others held the same beliefs and ideas he did: “It made me feel much better about sharing how I felt when I knew there were others who had the same ideas that I had.” An additional student found the online space to be a welcome alternative to traditional classroom conversations, responding, “I enjoyed the fact that it felt removed from the classroom environment….This allowed for a different environment and mode of speech that I would not normally tie to academic conversation.”

Student interest. Some students perceived the Twitter discussions to be more interesting than those they engaged in during class. One student found the 140-character limit to be a helpful characteristic that assisted him in thinking through these complex topics in manageable ways: “[The character limit] allows for concise commentary on the novels…without requiring lengthy reflections on concepts that may not have fully developed.” This student noted a benefit resulting from the concise requirements of Twitter. This benefit was echoed by others: “I thought Twitter sparked more of a natural conversation because it wasn’t in class and traditionally ‘academic’ in nature.”

Although the goal of this course was to have students develop positionalities on social justice issues, especially those portrayed in the YAL they read, and to then take those stances and voice them to the larger audience of Twitter, we concluded that PSTs noted benefits from the dialogic aspects of Twitter. These aspects included students and audience, student comfort, and student interest. Additionally, the data suggested that there were benefits for passive participants as well; those students who did not post their own ideas but only read the posts of their peers noted a benefit from thinking about the points of view of others.

Difficulty Extending In-Class Conversations

Aside from the benefits noted, the data also suggest that students experienced a variety of difficulties as they attempted to transition from the more traditional in-class conversations to those on Twitter.

Extending in-class conversations. We found that students were uncertain how to use Twitter to extend and build on their rich, provocative in-class conversations. They experienced difficulty using in-class discussions as jumping off points for their online posts. In her course evaluation, one student found “beginning conversations online was difficult and could make people feel uncomfortable.” Another student shared, “It was tough for me to transition between class and posting on social media. It seemed a little forced to me at times, so it was kind of harder than normally posting things on Twitter.” These student comments suggest that they struggled with expanding what they saw to be an appropriate space for classroom (i.e., academic) discussions.

Using books that openly detail a variety of common misconceptions and stereotypes, our goal was to promote meaningful conversation about society and the many sociocultural identities housed under its umbrella, as well as the ways in which teachers can promote and affirm a socially just, eclectic, and diverse society. As such, the class read Shine by Lauren Myracle, a novel set in rural North Carolina that presents the realities of poverty, drug addiction, and homophobia. Discussion of the novel was intentionally steered to prod PSTs to consider their own beliefs/perceptions of people belonging to various regionalities and how social capital—or stigmatization—is often imbued within a particular region.

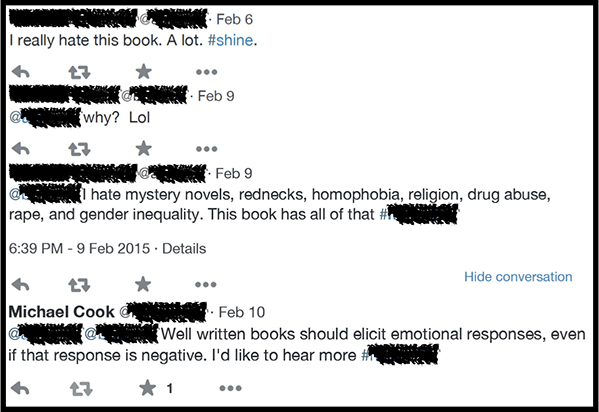

The difficulties PSTs experienced in connecting the use of Twitter and formal school learning can be seen well in an online interaction with one student. After a female student who had an emotional reaction to the novel tweeted, “I really hate this book. A lot,” the instructor asked her to think through her response and offer a rationale. She responded, “It’s all the things I hate and fear rolled into one book,” and “I hate mystery novels, rednecks, homophobia, religion, drug abuse, rape, and gender inequality. This book has all of that.” Figure 3 provides an excerpt of this conversation.

This was a prime opportunity to question her stance, and she was encouraged to elaborate. She had said all she was going to say, however— at least online. Clearly, she had experienced a powerful reaction to the novel, one in which she struggled to articulate clearly. In class, this student opened up about her strong response by discussing her experiences with a gay brother and the negative and hurtful comments about him that she often fought against. Based on these somewhat contrastively intimate responses, she was uncertain how to (or if she, in fact, could) share her thoughts on the issue online, especially given her very personal connection and previous experiences with this topic away from school. Thus, Twitter did not serve as a viable forum for her to share her position on the matter.

Critical classroom dialog. Much of the student conversations that were critical in nature were relegated to the classroom, and the discussions on Twitter tended to be less provocative. One student captured this outcome well by stating, “Unfortunately, some students simply used the Twitter responses to post single line comments about whether or not they liked a novel.” Moreover, the data suggest that students did not use the online dialogic space to support the critical analysis and development of positionalities the way the structure and scaffolding of in-class interactions did.

In her evaluation, one student said, “While I understand where you were trying to go with the Twitter conversations, I did not find this to be useful. I found myself sharing more in class.” As this student, and a variety of her peers stated, shifting their conversations and, more importantly, their analytical lenses and voices, from in-class discussions to the online space of Twitter proved to be difficult for many.

This disparity between online and in-class discourse was, perhaps, best demonstrated during discussions of three novels: Walter Dean Myers’s (1999) Monster, Gene Luen Yang’s (2006) American Born Chinese and Steven Kluger’s (2008) My Most Excellent Year: A Novel of Love, Mary Poppins and Fenway Park. Monster was chosen to elicit discussions about racial stereotypes and to help students begin to examine the roles they play in either promoting or fighting against such beliefs. American Born Chinese was also included to help students think about, discuss, and act toward issues of identity and belonging and the stereotypes that accompany ethnicities different from our own.

My Most Excellent Year was selected to facilitate authentic discussions around sexual orientations, particularly those that exist on the margins of heterosexuality. See Table 3 for examples of the contrast between the types of comments students made during in-class conversations and those they posted on Twitter.

Table 3

Class Versus Twitter Discussions

| Book | Class Discussion | |

| Monster | “We see this all the time on the news. A young black man gets accused of something, and we all assume he did it.” “This is the first novel I’ve read that forced me to question why I make the assumptions I do. It’s uncomfortable.” “When we use the label ‘monster,’ what criteria are we using? And how much of it is based on race and our fears?” | “I don’t really think any of the characters in the book are considered a ‘monster.’” “I just thought of it now, but I think monster is comparable to MMEY in terms of formatting.” “I wonder what’s his parents’ version of a monster. Also how hard it is to see that in their own son.” |

| American Born Chinese | “Yang’s use of the visual really makes it hard to ignore the fact that if we each created a mental representation of someone from China, I’m sure they would include at least some of this character’s traits.” “It’s the jokes that force us to ask why. Why are we laughing? Is it really funny? Or is it just an unconscious response to keep us from examining ourselves?” “Why do you think Yang chose these visual examples of stereotypes? It’s like a slap in the face to the reader, impossible to ignore. Is this how we perceive Asians?” | I love how you’re able to get a totally new experience from reading them [graphic novels] over regular novels.” “I love how sarcastic this book is. It’s hilarious!” “The graphic novel format really makes it interesting to read.” |

| My Most Excellent Year | “It’s ridiculous that anyone would think there is one homosexual experience. That’s like suggesting that all heterosexuals are exactly the same and lead the same lives.” “That’s true that all homosexuals don’t experience the world the same, but in many ways, they do share the experience of being stereotyped and judged.” “Teens need to be introduced to these types of books. They want to better understand the world they live in.” | “One of Kluger’s themes was to accept everyone who came into your life.” “It’s very stereotypical (and somewhat true) to have Augie be the one that is obsessed with theatre.” “I have best friends just like Augie, being a theater major.” |

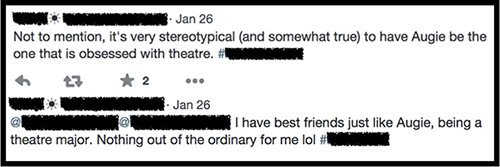

Surface-level Twitter discussion. As demonstrated by these examples, students struggled to engage via Twitter in the same deep, critical conversations they had in the classroom. The in-class conversations the PSTs engaged in allowed them more authentically to explore issues of social justice. Discussing My Most Excellent Year during class, students actively problematized the idea of heteronormativity by questioning their and their peers’ views and assumptions about homosexual stereotypes. When they used Twitter to analyze characteristics problematized in the text, they generally focused only on the character and did not take the next step to society (text-to-world). For example, when one student broached the subject of homosexuality in her post (see Figure 4), there was no response or further clarification to take the discussion further.

Students’ tweets fell short of prompting dialog that matched the critical analysis engaged in during class. In other words, the critical dialog about race, sexuality, and stereotypes were almost wholly constrained to the classroom. While the conversations in class evoked critical analysis of concepts such as the judicial system in the U.S., as well as assumptions about people of color, student tweets were grounded in the texts themselves.

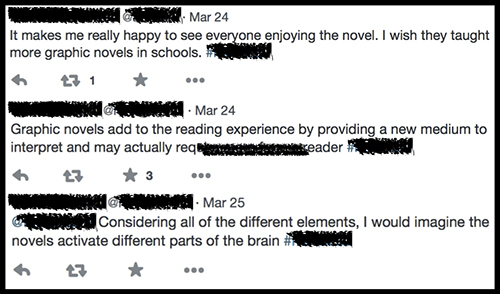

With regard to Yang’s (2006) novel, most posts were about the graphic format itself and less about the content (see Figure 5 for examples). Overall, students stopped short of using the online space to examine their experiences reading and connecting to the novels, whereas in class they were overwhelmingly successful in engaging in social justice conversations and positionality development in more powerful ways.

Other students resorted to using Twitter to share pedagogical ideas and evaluations of texts, rather than transferring the content of critically oriented in-class conversations to the online space. One student said, “Books can be the best learning tools, but only if they represent reality.” A peer responded, “True—I think the power of books like this in the classroom require a contrast to be effective in any way.” While these statements note students’ ability to connect their own experiences and future careers (i.e., transitioning from PSTs to education professionals) with those in the novel, they stop short of making the broader connections to the world they live in, the social issues represented, and their own voices for change. In short, many students focused solely on their own interactions with the novels (as was true in Rosenblatt, 1966) but consistently fell short of engaging in sociopolitical critique and critical reflection (as described in Howard, 2003).

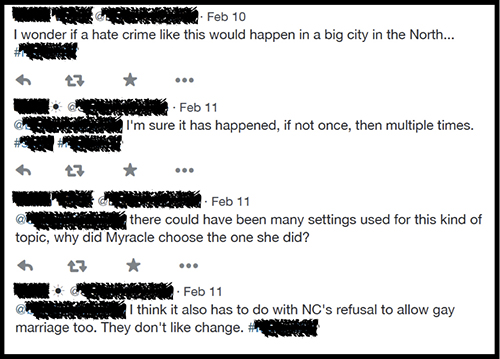

Furthermore, while some students mentioned relevant social justice issues in their Twitter posts, the posts themselves were often geared toward acknowledging the appearance of the issue in the text than toward discussing the implications for society—and secondary classrooms. For example, one student posted, “I appreciate Shine for its realistic portrayal of homosexuality.” Another stated, “I wonder if a hate crime like this would happen in a big city in the North,” prompting the response, “I’m sure it has happened, if not once, then multiple times” (see Figure 6).

This, however, is as far as these conversations went, at least with regard to using the issue of homophobia to connect to society and to discuss the need for change. In class, however, students engaged in socially relevant conversations of the issues discussed in the novel. These conversations included noting the fact that the negative stereotypes of homosexuals continues to be problematic in the U.S., with comments such as, “Why does it take a book like this to get us talking about an issue that is clearly a national problem?” and affirmation of the need to help others examine their own assumptions of homosexuality, which were seen in statements like, “If we all don’t question our own beliefs, we’ll never see a day when it’s truly okay to be gay.” Students seemed unsure how to, or else were unwilling to, negotiate the social dimensions of the microblogging space (especially toward social justice aims) with their perceptions of what forms schooling experiences should take.

Implications

The notion of hybrid pedagogy allows educators to extend conceptualization of the physical, social, and academic elements of the traditional classroom to include those conversations and interactions that occur online (Stommel, 2010). Additionally, as we examined and represented our findings, our understanding of transactional theory likewise encapsulated students’ experiences with Twitter. We understand each student’s reaction to the dialogic space to be unique to his or her person. Several students appreciated the dialogic space provided by Twitter as in the following responses:

- “[It] helped me think more deeply about each book and situation.”

- “It opened up a unique means of communication and allowed us to engage in discussions with authors, teachers, and others who have read the book.”

- “Twitter made us all more comfortable with one another by allowing us to communicate through an already popular form of social media.”

Yet another student noted an enjoyment and personal connection via Twitter by stating,

I enjoyed the fact that it felt removed from the classroom environment, as all forms of social media tend to be. This allowed for a different environment and mode of speech that I would not normally tie to academic conversation.

Another student acknowledged that, “because Twitter is a site I use for my personal thoughts, I did not mind using it for class participation, but I was sometimes unsure what I could share.” This sentiment was not uniformly shared, however. One of her peers wrote, “It was weird to have [Twitter] be a requirement of the class.”

Negotiating Dialogic Formats

PSTs also experienced difficulty in negotiating the two dialogic formats—the face-to-face, in-class setting and the asynchronous, online environment. In other words, many students found a requirement to use Twitter for class odd, as they struggled to reconcile the relationship between what they saw as academic (in-class) conversations and those they felt were part of their personal lives (Twitter).

In his course evaluation, one student described this relationship as “sometimes awkward. I talk in class because it helps me learn, it’s expected and I know my classmates are listening to me, but on Twitter I wasn’t always sure who I was talking to.” Statements like this reflected the difficulty students experienced in moving their academic conversations into the online domain. Throughout the semester, PSTs struggled to share their intimate ideas in the online environment of Twitter, they did not struggle to share their ideas in the more traditional space and audience of the classroom.

The tensions between privacy and sharing personal information have been documented (Krugger-Ross et al., 2013; Van Manen, 2010). For example, many student posts discussing Shine included comments such as, “I think there’s power in these books,” and, “[The author] was smart to put the setting of the book in the south because there are many prejudices there.” In class students discussed the relationships between the homophobia and small town, rural stereotypes and their own lives and hometowns. The data suggest an incongruent relationship between the public dialogic space and the willingness to open up and post the stances and thoughts associated with social justice issues.

Tweeting for Social Justice?

Twitter conversations that discussed students’ reactions to the YAL texts studied during the course presented another way to understand Rosenblatt’s (1938) transactional theory and allowed us to understand the extent to which students were developing and reorienting their positionalities and interrogating their own prejudices and privileges. Although students gained practice and experience engaging with social justice issues throughout the semester, they continued to struggle channeling their own emotions and responses into lucid statements that either pointed out injustice or promoted a social justice agenda.

For example, one student commented that she experienced difficulty sharing her thoughts on such complex thoughts in such a small space (i.e., character limitations): “I do not like trying to make important posts in just a sentence or two without being able to explain my thinking.” Another student noted that as time passed, it became more difficult to share social-justice-oriented posts online, stating, “I think it was tougher for me later in the semester because our class talks were getting very heavy, and I never really knew how to talk about that on Twitter.”

Thus, while the course content opened up conversation around issues often ignored in traditional classroom settings and students frequently engaged certain issues of social justice, these conversations were largely connected to the novels and fell short of connecting thematic elements of the text to societal realities. We, likewise, discerned little evidence of the PSTs examining their own sociocultural identities. This finding was, perhaps, unsurprising given PSTs’ historically documented hardships recognizing and problematizing their own sociocultural identities. They struggled to negotiate their own privileges and develop commitments to social justice. Last, PSTs almost never discussed how they would broach issues of social justice with their own students, preferring instead to talk about instructional possibilities of the novel.

Seeking a Safer Space

In examining the intersection between Twitter and its conduciveness to support PSTs’ social justice positionalities, our findings suggest that despite its popularity the forum did not prove to be an organic forum for students to engage social justice issues. Students struggled to utilize the dialogic space of Twitter—one they use for their personal lives—to analyze, critique, and voice the need for change in society.

In-class conversations were significantly more thoughtful, critical, and provocative than were discussions via Twitter. Although in many of the in-class discussions students critically analyzed the issues of racism, sexuality, and stereotyping in the novels and allowed students to make connections between the novels they read and the society in which they live, most student tweets discussed the books themselves (i.e., format, character traits) and to a lesser extent, teaching ideas. In other words, the comments in which students shared responses to the injustices they encountered through the readings and those that demonstrated their abilities to develop and use new positionalities were almost wholly made in class. Few tweets included students taking social stances and promoting new ways of thinking and acting.

This finding perhaps corroborates scholarship that speaks to the tensions between social media and privacy (Krugger-Ross et al., 2013; Van Manen, 2010). Thus, while hybrid pedagogy allowed for an extension of the in-class conversation, it did not offer a space for sustaining and extending the conversation in a critical way.

Interestingly, two of the theoretical frameworks applied to the study—transactional theory and the theory of hybrid pedagogy—almost seemed to work against each other, as students elected to focus on their own reactions to the novel rather than interrogate in an online, public forum the sociopolitical issues at the heart of the YAL texts. While students’ opinions of using Twitter for academic purposes varied, students consistently expressed difficulty using Twitter in a critical, open way. This reticence seemed to stem largely from the fact that Twitter, because of its public qualities, did not offer a safe space in which to articulate and discuss matters of social justice. If, as research overwhelmingly suggests, developing a social justice positionality is difficult, using social media perhaps augments this trepidation.

Twitter continues to be a venue that allows students to extend in-class conversations. Just as students respond differently to texts, so did they respond differently to the use of Twitter for academic purposes. While some students found it difficult to repurpose a social media platform they generally use for their personal lives for academic purposes, others enjoyed the activity. Teachers who use Twitter in their classroom should, thus, use it as one tool to promote and extend conversation and understand that its popularity does not guarantee that all students will enjoy the experience equally. Twitter, then, should be but one conversational tool a teacher educator employs.

Contextual Incongruity

Beginning to grapple with complex issues, such as those related to social justice, requires students to rethink their traditional classroom participation and to expand not only their ways of sharing but also the spaces in which they share themselves. This process can be complicated and may be more easily accomplished in the safety of the classroom and under the guidance of the instructor. Thus, Twitter may not be a forum well-suited for PSTs in the nascent and emerging phases of their social justice positionality.

Because Twitter may only compound the difficulties students’ experience developing their social justice positionalities, providing less public opportunities for students to work through their biases and prejudices. Writing exercises and in-class conversations may prove more suitable tasks for fostering this intimate form of growth.

Should a teacher educator wish to engage social justice issues on Twitter, the students involved should be more advanced in their social justice positionality. This study may have gleaned different findings if data had been collected from a graduate level critical race theory or social justice course, classes likely populated by students with more advanced orientations to social justice. This established confidence might provide for richer, bolder conversations on Twitter and provide a means for students to evolve into more publically and politically active change agents. Thus, Twitter instruction should be tailored to and differentiated for its students. .

Conclusion

Entering this study, we were interested in the ways in which students would, if at all, utilize Twitter to develop and share their positionalities toward social justice issues. Given that Twitter is a frequently used (and preexisting for most) dialogic space for students, it provided students the opportunity to discuss issues such as race, gender, and sexuality that arose from class readings and to extend their in-class conversations into the online world of social media.

Our findings suggest a disparity between the benefits students perceived from utilizing Twitter for educational purposes and the difficulties the data suggest they experienced in using the space to cultivate their own social justice identities, as evidenced by a lack of reflection on this development. In other words, while students noted benefits from utilizing the microblogging tool for class, those benefits were associated more with personal learning than with developing social justice positionalities. Further research is necessary to tease out the differences between what students saw as benefits of Twitter and the hurdles they encountered in developing positions and voices toward social justice goals while online.

Additionally, the data point to the necessity of providing students with scaffolding and modeling as they begin exploring the online space of Twitter to discuss and problematize the social justice issues they engaged in the YAL of the course. Regardless of the scaffolding provided by teacher educators, the findings from this study suggest that PSTs struggled with using Twitter to grapple with these social and complex issues and often circumvented the instructor’s guidance and modeling in an effort to stay safely within their own comfort zones.

The public nature of Twitter ultimately affects students’ abilities and, at times, willingness to simultaneously develop their positions and beliefs and post their voices for social change for the world to see. That is, the PSTs in our study were unable to extend and expand the socially critical discourse they engaged in during class by transitioning to the dialogic space of Twitter.

Still, we maintain hope that Twitter, YAL, and social justice can work synergistically. Though our findings suggest that Twitter was not best suited for helping PSTs develop and reorient their social justice positionalities, our analysis revealed that Twitter proved helpful to students in many ways and would perhaps serve as a more beneficial platform when used with a group of PSTs who are more advanced in their social justice orientation at the class’s onset. In order to use Twitter for social justice purposes, teacher educators should first consider ways in which their online pedagogies can support students’ critical engagement of various social justice issues while microblogging.

Teacher educators must ask the right questions, which are often the hardest ones. They must provide explicit instructions to students and make a point to tweet alongside students, engaging their ideas and prompting them to extend, synthesize, and problematize the issues at hand. At times, they must model vulnerability and push students beyond their comfort zones in order for them to move beyond their particularized idea of normal and usher them into the diverse milieu of the classroom—and the world.

References

Alsup, J., & Miller, sj. (2014). Reclaiming English education: Rooting social justice in dispositions. English Education, 46(3), 195-215.

Bell, L. A. (1997). Theoretical foundations for social justice education. In M. Adams, L. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice: A sourcebook (pp. 3–15). New York, NY: Routledge.

Bell, L. A. (2002). Sincere fictions: The pedagogical challenges of preparing white teachers for multicultural classrooms. Equity & Excellence in Education, 35(3), 236-244.

Boser, U. (2014). Teacher diversity revisited: A new state-by-state analysis. Retrieved from the Center for American Progress website: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/report/2014/05/04/88962/teacher-diversity-revisited/

Boyd, A., & Pennell, S. (2015). Batteries, big red, and busses: Using critical theory to read for social class in Eleanor & Park. Study and Scrutiny: Research on Young Adult Literature, 1(1), 95-124.

Britzman, D. (2003). Practice makes practice: A critical study of learning to teach. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Bull, K.B. (2011). Connecting with texts: Teacher candidates reading young adult literature. Theory Into Practice, 50, 223-230.

Charmaz, K. (2000). Constructivist and objectivist grounded theory. In N.K. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 509-535). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory. A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London, UK: Sage

Cochran-Smith, M. (2010). Toward a theory of teacher education for social justice. In M. Fullan, A. Hargreaves, D. Hopkins, & A. Lieberman (Eds.), The international handbook of educational change (2nd ed., pp. 445-467). New York, NY: Springer.

Cohen, J. (1968). Weighted kappa: Nominal scale agreement provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychological Bulletin, 70(4), 213.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Duggan, M., Ellison, N., Lampe, C., Lenhart, A., & Madden, M. (2014). Demographics of key social networking platforms. Retrieved from The Pew Research Center website: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/01/09/demographics-of-key-social-networking-platforms-2/

Farwell, T. M., & Waters, R. D. (2011). Cross-university collaboration through micro-blogging: Introducing students to Twitter for promoting collaborations, communication and relationships. In C. Wankel, M. Marovich, K. Miller, & J. Stanaityte (Eds.), Teaching arts and science with the new social media (Vol. 3, pp. 297-320). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

Forte, A., Humphreys, M., & Park, T. H. (2012, June 4-8). Grassroots professional development: How teachers use Twitter. Paper presented at the sixth annual International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media. Retrieved from https://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/ICWSM12/paper/download/4585/4973

Gay, G., & Howard, T.C. (2000). Multicultural teacher education for the 21st century. The Teacher Educator, 36(1), 1-16.

Gay, G., & Kirkland, K. (2003). Developing cultural critical consciousness and self-reflection in preservice teacher education. Theory Into Practice, 42(3), 181-187.

Gerstein, J. (2011). The use of Twitter for professional growth and development. International Journal on E-Learning, 10(3), 273-276.

Glaser B. G. & Strauss A. (1967). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New Brunswick, NJ: Aldine Transaction.

Glasgow, J.N. (2001). Teaching social justice through young adult literature. English Journal, 90(6), 54-61.

Golden, J., & Christensen, L. (2008). A conversation with Linda Christensen on social justice education. English Journal, 97(6), 59-64.

Grosseck, G., & Holotescu, C. (2008, April). Can we use Twitter for educational purposes? Proceedings of the 4th International Scientific Conference: eLearning and Software for Education. Retrieved from https://adlunap.ro/else/papers/015.-697.1.Grosseck%20Gabriela-Can%20we%20use.pdf

Hackman, H. (2005). Five essential components of social justice education. Equity & Excellencein Education, 38, 103-109.

Haritaworn, J. (2008). Shifting positionalities: Empirical reflections on a queer/trans of colour methodology. Sociological Research Online, 13(1), 13.

Hayes, C., & Juarez, B. (2012). There is no culturally responsive teaching spoken here: A critical race perspective. Democracy & Education, 20(1), 1-14.

Hayn, J.A., Kaplan, J.S., & Nolen, A. (2011). Young adult literature research in the 21st century. Theory Into Practice, 50(3), 176-181.

Hooks, B. (1994) Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom, London, UK: Routledge.

Howard, T. C. (2003). Culturally relevant pedagogy: Ingredients for critical teacher reflection. Theory into Practice, 42(3), 195-202.

Jaworowski, S. (2010). Twitter in action: One professor’s experience. In Proceedings of the TCC Worldwide Online Conference (Vol. 2010, No. 1, pp. 110-117). Retrieved from the LearnTechLib: https://www.editlib.org/j/TCC/v/2010/n/1/

Kim, M., & Cavas, B. (2013). Legitimate peripheral participation of Preservice science teachers: Collaborative reflections in an online community of practice, Twitter. Science Education International, 24(3), 306-323.

Kluger, S. (2008). My most excellent year: A novel of love, Mary Poppins and Fenway Park. New York, NY: Dial Books.

Kruger-Ross, M., Waters, R.D., & Farwell, T.M. (2013). Everyone’s all a-twitter about Twitter in the classroom: Three operational perspectives on using Twitter in the classroom. In K. Kyeong-Ju Seo (Ed.), Using social media effectively in the classroom: Blogs, wikis, Twitter, and more (pp. 117-130). New York, NY: Routledge.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1999). Preparing teachers for diverse student populations: A critical race theory perspective. Review of Research in Education, 24, 211-247.

Maher, F. A., & Tetreault, M. K. (1994). The feminist classroom: An inside look at how professors and students are transforming higher education for a diverse society. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Martin, R. J., & Van Gunten, D. M. (2002). Reflected identities: Applying positionality and multicultural social reconstructionism in teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(1), 44-54.

McCool, L.B. (2011). The pedagogical use of Twitter in the university classroom. (Master’s thesis; Paper No. 11947). Retrieved from http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/11947

McIntyre, A. (2002). Exploring Whiteness and multicultural education with prospective teachers. Curriculum Inquiry, 32(1), 31-49.

Miller, D. (1999). Principles of social justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Myers, W.D. (1999). Monster. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Myracle, L. (2011). Shine. New York, NY: Amulet Books.

National Council of Teachers of English and National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education. (2012). NCTE/NCATE standards for initial preparation of teachers of secondary English language arts, grades 7-12. Retrieved from http://www.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Groups/CEE/NCATE/ApprovedStandards_111212.pdf

Nicholson, J., & Galguera, T. (2013). Integrating new literacies in higher education: A self-study of the use of Twitter in an education course. Teacher Education Quarterly, 40(3), 7-26.

North, C. E. (2006). More than words? Delving into the substantive meaning (s) of “social justice” in education. Review of Educational Research, 76(4), 507-535.

Rich, A. (1980). Compulsory heterosexuality and lesbian existence. Signs, 5(4), 631-660.

Rodesiler, L., & Pace, B. G. (2015). English teachers’ online participation as professional development: A narrative study. English Education, 47(4), 347.

Rosenblatt, L. (1938). Literature as exploration. New York, NY: Appleton-Century.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1966). A performing art. The English Journal, 55(8), 999-1005.

Sensoy, O. & DiAngelo, R. (2012). Is everyone really equal? An introduction to key concepts in social justice education. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Singer, J., & Shagoury, R. (2006). Stirring up justice: Adolescents reading, writing, and changing the world. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 49(4), 318-339.

Sleeter, C. E. (2012). Confronting the marginalization of culturally responsive pedagogy. Urban Education, 47(3), 562-584.

Stommel, J. (n.d.). Getting started with Twitter. Retrieved from http://www.jessestommel.com/Introduction_to_Twitter.pdf

Stommel, J. (2012, March 10). Hybridity, pt. 2: What is hybrid pedagogy? Hybrid Pedagogy. Retrieved from http://www.hybridpedagogy.com/journal/hybridity-pt-2-what-is-hybrid-pedagogy/

Thomas, D.R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237-246.

Thomas, G. (2011). A typology for the case study in social science following a review of definition, discourse, and structure. Qualitative Inquiry, 17(6), 511-521.

Van Manen, M. (2010). The pedagogy of Momus technologies: Facebook, privacy, and online intimacy. Qualitative Health Research, 20, 1023-1032.

Villegas, A.M. (2007). Dispositions in teacher education: A look at social justice. Journal of Teacher Education, 58(5), 370-380.

Wells, G. (1999). Dialogic inquiry: Toward a sociocultural practice and theory of education. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Whipp, J.L. (2013). Developing social just teachers: The interaction of experiences before, during, and after teacher preparation in beginning urban teachers. Journal of Teacher Education, 64(5), 454-467.

Wolk, S. (2009). Reading for a better world: Teaching for social responsibility with young adult literature. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 52(8), 664-673.

Wright, N. (2010). Twittering in teacher education: Reflecting on practicum experiences. Open Learning, 25(3), 259-265.

Yang, G.L. (2006). American born Chinese. New York, NY: First Second.

Author Notes

Mike P. Cook

Auburn University

Email: [email protected]

Jeanne Dyches Bissonnette

Iowa State University

Email:[email protected]

![]()