Technology Integration for Writing Development

One of the most dramatic developments of the digital information revolution has been the explosion of new mediums for writing and communication. Video, podcasts, and many types of digital options provide new ways for people to share ideas and experiences online. These new forms of expression present a change in what it means to be literate in contemporary society and challenge our ideas of how to teach literacy (Lankshear & Knoble, 2011).

The definition of literacy now includes digital approaches to accessing, processing, and transmitting knowledge. Thus, a compelling need exists for the integration of digital literacies into virtually every aspect of instruction in today’s classrooms (Hobbs, 2011; Judson, 2010; Kajder, 2007; Luce-Kapler, 2007; Merchant, 2010; Sweeney, 2010). Such a mandate requires teacher candidates (TCs) to understand the new literacies and learn how to apply them in instruction skillfully.

In this article, social media is defined as Internet-based tools for disseminating information, discussing, developing, and engaging in digital networks (Lankshear & Knoble, 2003). In particular, TCs must be able use what are described as Web 2.0 sites such as Wikipedia, YouTube, and Facebook. These sites are core tools that have democratized the Internet by enabling anyone to share information (Jenkins, 2009).

Teacher education faculty, (many of whom taught long before the digital revolution), as well as TCs, must be equipped to draw upon a variety of literacies in order to tap into the complex social worlds of their future pupils. Developing this expertise will take time. This project represents an initial step toward integrating digital literacy into teacher preparation.

The Write for Your Life Project (W4YL) provided TCs with hands-on experiences working with commonly used digital media. The project was situated within sociocultural literacy theory as presented by the New London Group (1996, 2000). Researchers within this framework are often concerned with moving beyond viewing reading and writing as discrete, isolated skills. They view language and literacy as social practices that embody a broad set of multiple literacies, ranging from texting to video games to using social networks in the classroom (Larson, 2009; Sweeny, 2010; Wolsey & Grisham, 2011).

Within this framework, multiple literacies may be accessed through available designs, new designs, and the redesign of existing processes. With regard to writing pedagogy, sociocultural theory emphasizes the need for TCs to have authentic opportunities to (a) draw upon their own experiences to write using new, as well as older, standardized literacies; (b) apply these experiences to understanding the research-based best practices learned in their courses; and (c) incorporate their own philosophical stance toward teaching writing.

The purpose of the W4YL project was to increase TCs’ skills across the various writing literacies. The project employed social networks, blogging, texting, and online modules. Utilizing Calkins’ (1994) Writing Workshop Approach, the TCs learned to use technology for developing daily personal writing, devising writing-based minilessons, planning and participating in peer conferencing, and publishing final products.

This article describes how the WFYL projected helped TCs integrate traditional approaches to teaching writing with new literacies. We analyzed TC writing samples and survey responses to determine the effectiveness of the project. Thus, we recommend steps for more effectively integrating writing and technology across the content areas.

The research questions that guided our inquiry were as follows:

- What are TCs’ previous attitudes and experiences toward teaching writing and using social media?

- How do teacher candidates respond to the use of social media as a tool for teaching writing?

- How can university faculty members use W4YL effectively to integrate writing and technology across the content areas?

Project Rationale

Findings from a longitudinal study conducted by the Teacher for New Era (TNE) Literacy Project provided a key motivation for this study. The investigation revealed that TCs at our university were experiencing challenges in the area of writing (Barnard, Collier, Duprez, Shelf, & Stallcup, 2009). In the first 2 years of the study, researchers from various disciplines in Education, Anthropology, and English explored how prospective elementary TCs wrote, how they were taught to write, and how they applied these writing skills to their student teaching experiences.

Findings indicated differences between the concepts of good writing across colleges and disciplines. For example, some disciplines valued the writing process, whereas others strictly focused on writing mechanics. Moreover, TCs experienced inconsistencies between the approaches that were used to teach writing in methods courses and the instructional approaches they observed in schools (TNE Final Report, 2009).

The study revealed several other factors that affected the TCs in the area of writing (Grisham & Wolsey, 2011). First, many of our TCs spoke English as a second language, yet there were few writing and language supports within the university for these students. Second, the integration of the Performance Assessment for California Teachers not only required TCs to have a greater understanding of academic language, but it also implicitly measured their ability to articulate, reflect, and integrate writing consistently into their teaching as a requirement to graduate from the teacher education programs.

The primary motivation for the W4YL project was the recognition that writing itself is changing as society embraces digital technology. Teacher education faculty members who do not recognize these changes and fail to prepare TCs for the new realities are doing their students a disservice (Collins & Halverson, 2009; Wesch, 2009). The next generation of teachers will need to embrace commonly used tools to meet the needs of TCs and their future pupils in the digital age effectively.

Teacher educators must continue to discuss, explore, reevaluate, and redesign pedagogical approaches to prepare teachers effectively as writers and teachers of writing. For example, Street (2003) claimed that TCs’ attitudes toward teaching and writing significantly impacted learning outcomes. He contended that students’ histories as writers have a long-term effect on their abilities as future writing teachers. Thus, both classroom and onsite teaching experiences need to be situated within contexts in which TCs frequently reflect upon their attitudes toward writing.

Similarly, Street and Stang (2008) asserted that, “not only do students need pedagogical applications, but reflective opportunities to examine writing in their lives” (p.61). Thus, W4YL was designed for TCs to draw upon their strengths as writers, in addition to supporting them in mastering new writing skills using various forms of technology.

Building Digital literacy

Current research indicates that technology integration in the area of writing is a powerful tool for enhancing writing development and the instruction of writing across the content areas. Wilder and Mongillo (2007) found that the integration of technology tools such as referential communication tasks (a series of game-like online tasks in which students must describe a set of pictures) and online modules increased the expository writing skills of TCs. They found that online writing provided multiple exposures to academic language that were of critical importance to TCs’ writing development.

Furthermore, Weingarten and Frost (2011) claimed that online writing tools such as wikis and blogs offer more opportunities for students to collaborate in the authorship process. This collaborative process of writing scaffolds TCs’ learning, which allows them to redefine authorship, thus promoting the merging of old and new literacies.

The integration of digital literacies in the content areas impacts not only teacher preparation, but also pupil outcomes. For example, Judson (2010) asserted that technology literacy gains were highly correlated with increased language arts content area skills in students. He stated, “If gains are made in technology literacy, then gains in traditional content areas would only be expected if students are provided ample opportunity to apply their new technology ability for content” (p. 281).

The integration of digital literacies to teach writing pedagogy assists in broadening traditional concepts of writing to include visual images, video compositions, movies and other multimodal tools (Bruce, 2009; Whitin, 2009). Whitin (2009) argued that such contexts for learning to write deepen comprehension and literacy skills, promote critical thinking, and allow for more peer engagement. Additionally, such approaches require the collaboration of key content area faculty. Based upon these recommendations, we designed an online community that would support the development of digital literacy skills.

Methods

Project Design

The W4YL project team consisted of four professors—two from secondary education (one technology specialist and one social studies specialist), one from elementary education, and one from the English department. The W4YL project was piloted in two courses with a total of 45 TC participants. The participants included TCs enrolled in an elementary methods course (n = 17) and a secondary education course (n = 29).

The TCs enrolled in the elementary course were part of a fourth-year accelerated undergraduate cohort, whereas those in the secondary education course were part of a fifth-year preparation program. We used an embedded mixed-methods approach to examine our participants. Although our study drew mostly upon qualitative, open-ended survey responses and informal interviews, we also used quantitative data to triangulate and highlight key themes (as in Creswell & Clark, 2011).

TC participants completed pre- and postsurveys. The purpose of the presurveys was to determine students’ writing habits and their use of social media. They were asked to respond on a Likert scale to statements such as, “I think of myself as a writer,” or “I think of myself as technically literate.” The questions were designed to discover awareness of writing genres, attitudes toward writing, and writing styles.

The postsurveys included additional queries that focused on TCs’ experiences using the site created for the project and the potential applicability of social media in future teaching. Sample questions included, “How is writing on a social network (Facebook, Myspace) different from other types of writing?” and “How will the use of social networks and other online writing change the way students write?”

The project team worked collaboratively to develop the survey items to ensure construct validity. The team also defined key content terms used in the survey, such as social media, writing, and teaching. Thus, while the pre- and postsurveys had the same core questions, they were not identical.

The postsurvey addressed pedagogical applications of the W4YL project and overall satisfaction with using the site. Some questions included the following:

- “Do you think the W4YL site is helpful for you as a teacher?”

- “How could you use online writing as part of your teaching?”

- “Would you recommend that future classes use W4YL?”

Another key source of the qualitative data was student writing samples and course reflections. The instrument was validated for interrater reliability using all faculty project team members. Content validity was assessed online using a sample of enrolled students.

Developing a Social Network

The project team met several times to develop the W4YL social network. Team members decided that a social network could provide a platform for TCs to engage in multiple modes of digital writing. We considered using Facebook as a platform for TCs to explore writing and social media. However, we decided that a private space where TCs would be free to explore writing without the judgment of peers or family members who were not enrolled in the course would be more appropriate. We also wanted to provide structured support from the course instructors, in addition to peers who were trained to use the writing process and writing workshop to foster writing.

With this goal in mind, we created a digital writing sandbox, a private social network that was accessible only to our TCs and teachers. We used Drupal (www.drupal.org), a web-based, open source content management system, to create a website that provided TCs with a full social network experience.

We decided to use a simple format that also incorporated key features of many of the popular social networking formats, such as profile pictures, blogs, linking capabilities to outside web resources, status updates, and opportunities to send friend requests.

A unique network provides TCs with a safe space to explore and develop their identities as writers separate from their existing online identities (Foley, 2012). Figure 1 explains the purpose of the site and highlights why writing using social media is helpful to pupils in elementary and secondary contexts.

Figure 1. W4YL opening page.

Figure 1. W4YL opening page.

The team members had varying degrees of technological literacy from somewhat minimal to extremely proficient. We worked together to identify instructional activities and technological features of the site that would benefit all of the TCs. The site was designed to allow TCs and faculty to post status updates, write their own blogs, post to forums, comment on the writing of their peers in both classes, and participate in online chats. The two lead instructors created a blog on the site and encouraged TCs to comment on it. Additionally, each team member assisted in the development of a total of five online writing modules.

The writing modules were class assignments completed in the social network. The assignments were structured to help TCs critically examine various genres of writing and reflect upon integrating different technologies. The modules focused on Narrative Writing, Persuasive Writing, Modern Music, Writing and Advocacy, Autobiographies and Teaching, and Teaching Writing in Social Studies (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. W4YL writing modules.

Figure 2. W4YL writing modules.

Aligning Course Content

Teacher candidates in two courses participated in the W4YL project. The first course was a literacy/diversity course for elementary TCs. The TCs in this literacy course were required to write a minimum of two to three blog posts per week and participate in weekly writing challenges. The W4YL program participants read their blog entries during class sessions and received feedback from their peers.

In the middle of the semester, the TCs were encouraged to develop a writing seed idea, choosing one topic they wanted to explore in-depth and eventually publish. At the end of the semester, TCs participated in a publishing party, in which they read their final pieces aloud in class.

The team also wanted the site to serve as a functional resource for TCs. Thus, we compiled a list of Internet resources and other materials. These were outlined on a separate webpage. Students were encouraged to explore and analyze materials specifically regarding teaching writing and digital literacies in the classroom (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Internet resources.

Figure 3. Internet resources.

Additionally, the instructor posted writing minilessons and writing challenges that students were required to complete on a weekly basis (see Figure 4 for an example). These were used to encourage student writing and highlight writing techniques.

Figure 4. Writing minilesson.

Figure 4. Writing minilesson.

The second class that participated in W4YL was a social studies student teaching seminar for secondary TCs. The social studies course was largely centered on supporting TCs during their student teaching and developing a Teaching Event for the Performance Assessment for California Teachers.

The course also sought to support these TCs in any challenges they encountered when teaching social studies in a middle school or high school classroom. The TCs in this course used the W4YL website to

- Explore the applicability of online modules in a social studies classroom;

- Blog and respond to classroom concerns;

- Participate in online discussions, and

- Participate in a Skype presentation regarding communicating online with President Obama’s White House.

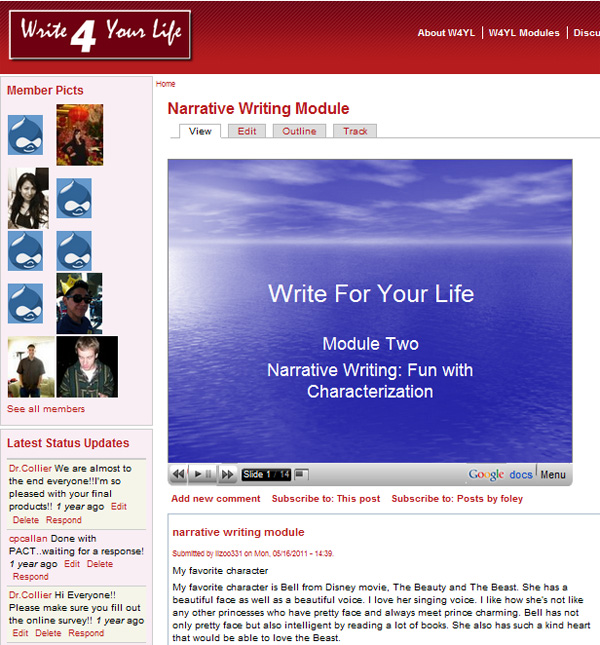

The second course instructor specifically emphasized how the online modules related to the use of autobiographies in instruction, the teaching of writing in the social studies classroom, and the development of classroom and schoolwide college-bound ethics. Figure 5 is a screen capture of one TC’s response to the module. TCs were also encouraged to respond to one another’s comments.

Figure 5. Narrative writing module.

Figure 5. Narrative writing module.

Applying the English Specialist Perspective

A faculty member from the English Department was added to the team to provide research-based advice regarding writing and the teaching of writing. His role also involved keeping the team informed about how traditional writing conventions, processes, and norms are being influenced by technology. Much of the dialog with the English specialist centered on which genres were considered to be valid forms of writing on the web.

For the team member who taught the literacy course, genres consisted of anything from science fiction to expository writing. In contrast, the social studies content faculty member most valued expository-based writing. Therefore, nonfiction writing, such as reports, editorial essays, and persuasive writing were emphasized in this project. The English specialist consistently conducted writing minilessons with TCs on the W4YL site. Minilessons were designed to assist TCs in devising topics for writing, making connections between teaching writing and technology, and modeling skilled writing.

Data Analysis

For the quantitative questions on the survey a codebook was developed for each item. These items were converted from an ordinal scale into a Likert scale to facilitate descriptive statistical analysis. However, because the survey was primarily qualitative, in accordance with the traditions of qualitative research, we also conducted a preliminary analysis of the qualitative items on the survey by writing analytical memos on emerging themes, similarities, and differences amongst the participating TCs. Additionally, faculty writing reflections and email communications were coded using the constant comparative method for analysis (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Silverman, 2009).

The team analyzed the data for emerging themes by comparing similarities and differences in responses as related to TC and faculty experiences with W4YL. Due to the small sample size we chose to code the data ourselves without using qualitative data software. This allowed more opportunities to triangulate key themes.

We wrote analytical memos to make connections between the codes, the participants, and the various variables that might have impacted TCs responses, such as the type of program they were in and the number of years in the program. The team even considered how our teaching philosophies might influence our analysis.

Codes that emerged for TCs included defining writing, challenges with implementing social media, opportunities for creative expression, criteria for determining valid references on the web, and previous exposure to technology. For faculty, codes included previous exposure and access to technology, challenges with integrating W4YL into existing course content, and varying social media proficiencies.

Findings

Attitudes and Experiences with Writing and the Use of Social Networks

Given the new commonplace uses of social networks as key writing and communication media, we first assessed the baseline skills of the program participants in this area. When initially surveyed to discover what they knew about teaching writing, in general, 31 (69%) of the TCs responded that they knew that writing was a process involving five stages. However, only 18 (40%) stated that power writing and journal writing were effective tools for teaching writing, suggesting that the project staff needed to demonstrate the usefulness of these tools.

As we expected, 33 (73%) of the TCs stated that instruction in grammar and punctuation was essential to writing development. Yet only, 9 (20%) stated that it was important for students to write on a daily basis. Surprisingly, only 6 (15%) of the respondents indicated that students’ cultural backgrounds and language development skills impacted opportunities to write. This finding suggested that TCs needed to be taught how social media can be used to provide additional support to literacy development and English language learning.

These responses show that before becoming involved in the W4YL project, the TCs in our study had a preliminary understanding of essential pedagogical skills needed to teach writing effectively. Prior to taking the courses in which they were enrolled for the W4YL project, all 45 participants were required to take a literacy instruction methods course. The responses indicated that some portion of those surveyed possessed an introductory understanding of writing pedagogy.

Additionally, we wanted to gain an understanding of TCs’ comfort levels with writing, in general. At the beginning of the pilot study in the presurvey, 13 (29%) of the TCs disagreed with the statement, “I see myself as a writer.” However, in the postsurvey at the end of the pilot study, only 5% of the TCs disagreed with the statement.

With regard to engagement in social networks, according to the presurvey, approximately 23 (52%) of the TCs responded that they used a social network several times a day. The most common social networks used by the participants were Facebook and Twitter, revealing that they had a foundation for using social media.

Social Media as a Tool for Teaching Writing

The responses to the effort to use social media to teach writing varied dramatically by discipline. Although the TCs in the literacy course were encouraged to “write for writing’s sake,” candidates in the social studies course had more definitive objectives regarding when they wrote, what they wrote, and how they used social media.

First, project participants had divergent views on what was considered to be valid writing based upon their discipline. For instance, one TC from the literacy course reported, “I see the benefits of an online blog/journal, but I feel there is too much nonsense that comes with that particular territory.” When further questioned, “nonsense” for this TC included the overuse of acronyms, students having limited exposure to “traditional writing conventions” and excessive access to nonschool-related information.

As might be expected, the literacy TCs had little exposure to the effective use of blogs for academic purposes. While some had their own blogs before taking the course and becoming involved in the WFYL project, they saw such writing as solely for informal purposes. Indeed, the literacy TCs, in general, appeared to be less convinced that social media could be validly used to teach writing, as the following comment by one TC shows:

Writing will become typing and spelling will suffer as acronyms will become the norm. Since blogs are typically instant, the revision process of writing will be skipped. I also think students will become defensive about their writing as they will now think everything they are thinking is worthy of being published to the masses. (TC survey response)

This TC raised several points that should be considered when attempting to integrate old and new literacies. Because blogging seems to be viewed as an instantaneous writing tool, teacher educators may need to design experiences that model how blogging can be used in each phase of the writing process.

The comment about student defensiveness suggests that this TC believed that future pupils may not be open to criticism or critique because what the teacher thinks is not important. They may feel entitled to publish whatever they are thinking. If this is true of students, then TCs must also have numerous opportunities for determining what high-quality writing is on the web and which audiences students are targeting.

However, several of the literacy TCs recognized that benefits can accrue from this process. For example, social media assisted them in developing key elements of traditional writing, such as voice, tone, style, and other literary elements. One TC commented, “It is more personal. I use my own voice and tone.” It appears that the TCs from the literacy course who saw the positive benefits of integrating digital media into teaching writing viewed writing as a socially constructed process versus writing as a mechanical process. Therefore, they believed that social media had tremendous potential classroom application. One TC from the literacy course stated, “I believe the more you write, the better writer you become.”

The percentage of all TCs who indicated that tools such as power writing and journal writing were effective pedagogical tools for enhancing writing development increased from 40% (18) to 80% (36) from the beginning of the course to the end of the project. Again, the TCs from the literacy course were somewhat more critical about the integration of social media as a tool for teaching writing. This case may be because these TCs had more training in literacy pedagogy and were, therefore, more critical about what they considered to be research-based best practices.

Interestingly, the TCs from the social studies course appeared to find social media more useful. One social studies TC commented as follows:

It gives students a chance to see what their classmates are writing, makes it more social, helps students to get to know each other, and helps the teacher to get to know the students by seeing how they interact. The teacher can also comment on students’ work right away. It’s more of a friendly conversation than a formal assignment. I feel it’s a more welcoming way to get students to write than, for example, a report. (TC Survey response)

This TC highlighted the importance of social interaction as part of the writing process. She discusses several benefits to using social media and digital writing, such as getting a deeper understanding of peers and immediate access to ongoing work.

The TC also identified the opportunity this approach provides for the teacher to observe and assess students informally as they engage in writing. However, the TC also referred to online writing as “more of a friendly conversation than a formal assignment.” Here, it is evident that the TC viewed online writing as an informal process, which raises the following questions:

- Will the TCs’ future pupils also see writing using digital media as informal writing?

- Will digital writing ever be perceived as a high stakes process that requires acute attention to detail by both teachers and students?

This TC’s response also demonstrates how sites such as W4YL can serve as safe spaces for writing. This concept of safe space allowed some TCs from both the literacy and the social studies courses to feel more confident with writing, developing a voice, and trying new genres.

In her writing reflection, one TC from the social studies course mentioned, “I’ve never been comfortable writing poetry, but I wanted to step out of my comfort zone.” One challenge that the program encountered was examining how university faculty members could encourage teacher candidates to “step outside of their comfort zones.” Faculty members provided weekly writing challenges to aid in this process, with the goal to use digital media as one of many strategies to teach writing pedagogy and also to encourage writing.

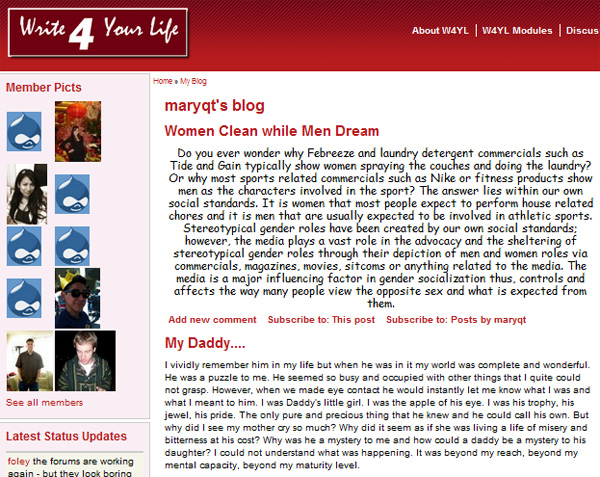

As a result, the types of writing products submitted varied greatly. For instance, of the 17 TCs enrolled in the literacy/diversity course, 11 (64%) wrote nonfiction works as their final pieces. However, the genres varied greatly and included poetry books, novelas/scripts, personal letters to loved ones, and travel guides to fantasy places. The course consisted of predominantly female students. Thus, most of their blog posts related to women’s issues such as love, relationships, motherhood, and friendship (see Figures 6 and 7 for examples).

Figure 6. TC Blog 1

Figure 6. TC Blog 1

Figure 7. TC Blog 2

Figure 7. TC Blog 2

Social Studies Faculty and Content Integration

Both the TCs and the social studies instructor struggled with the integration of old and new literacies into instruction. For example, identifying valid sources of information for social studies teachers and determining how technology can be used so that it does not limit but, instead, supplements the learning process, was a key area of inquiry. In a reflective journal, the social studies instructor wrote,

I learned much about how I personally, and some of my students remain current in our subject matter: we are still reading newspapers, magazines and books. You can’t take an iPad or a laptop to the breakfast table, and sometimes these are not the most convenient on the road.

Relative to social studies instruction, the social studies instructor and the social studies TCs grappled with the limitations of technology and the quality of what one finds on the Internet. For example, how should a teacher address, discuss, or protect students from unsolicited comments from the public in response to critical topics and current events? Privacy issues, as well as identifying and analyzing hidden political agendas, were also key themes.

Faculty Challenges with Technology Integration

As with most pilot projects, unexpected issues arose. With the W4YL project, these issues primarily involved technology. The technology breakdowns caused the faculty group to develop new troubleshooting strategies on an ongoing basis. The technology specialist, a faculty member in the team, not only had to resolve any potential sites issues, but also had to teach team members how to troubleshoot the issues for themselves. The following comment was made in the technology specialist’s field notes in response to challenges with posting pictures and other visuals on the site:

The picture thing has been problematic—but I added a new “module,” and this seems to work correctly now. I just added a blog to the site explaining what to do with old blogs with missing pictures (just edit and re-save them). So that seems to be OK—now on to figure out what is happening to the emails (still not working).

Thus, when technology breakdowns occurred, we not only needed a way to inform the team members, but we also had to inform the TCs of what to do and how their action would impact opportunities to fulfill course requirements. Again, this faculty member may have experienced increased workload issues because he not only had to resolve site-related issues but also needed to train the faculty and TCs on how to resolve any online issues.

As the project progressed, team members began to set personal goals for new technologies they wanted to learn and share with their students prior to the end of the project. Faculty members gained more autonomy in applying digital literacies and relied less on the technology specialist. However, these issues also demonstrated the need to feel confident and comfortable with technology before integrating a project of this type into the classroom.

Faculty Implications for Social Media and Writing Development Projects

Merchant (2010) said that effective integration of new literacies such as social media and virtual worlds requires a fundamental shift of what is defined as learning. “Rather than thinking new technologies can activate changes in practice, we should think about how changes in practice could create possibilities for using new technologies in innovative ways” (p. 148).

Overall, the collaborators agreed that the W4YL project was an innovative attempt to use more social media to encourage the development of writing pedagogy. According to the NCTE,

As basic tools for communicating expand to include modes beyond print alone, “writing” comes to mean more than scratching words with pen and paper. Writers need to be able to think about the physical design of text, about the appropriateness and thematic content of visual images, about the integration of sound with a reading experience, and about the medium that is most appropriate for a particular message, purpose, and audience.

With regard to attitudes and experiences toward teaching writing, we concluded that the site created safe spaces to write and share personal and academic matters. Oftentimes, technology integration using websites such as Blackboard and Moodle consists of fairly straightforward summaries of ideas or applications. The researchers concluded that the more we structured TC learning experiences to be personal by connecting writing to their own experiences, the greater the probability that these ideas will become meaningful parts of their conceptual ecology.

The consensus of both the TCs and faculty members was that the project increased awareness of the possibility of using current digital media tools such as Facebook, Twitter, Google Groups, and wikis in teaching writing. It also provided exposure to key vocabulary TCs need to use with such platforms. The focus on writing and teaching writing across content areas demonstrated that social media could be used to teach minilessons, to hold effective writing conferences, and extract writing topics from the daily lives of students.

This pilot project also revealed that processes and outcomes may differ by content area. For example, assignments involving nonfiction, expository-based essays may be more useful as a starting point for social studies content teachers than for those in language arts. Nonetheless, all genres of writing should be used and integrated across the content areas.

For social studies teacher educators, using technology in the classroom requires an ongoing dialog regarding how knowledge is constructed. Students are encouraged to view multiple perspectives and to challenge assumptions conveyed in the media they encounter online. In contrast, in a literacy/language arts classes, the orientation of the assignments may need to reinforce traditional grammar and vocabulary in addition to content.

When using social networks, teachers must redefine their roles and reflect upon how technology might facilitate the process. In both content areas, teachers must calibrate student efforts to find authentic and valid resources online. Some of the inquiry questions the social studies TCs explored were related to the use of social media and technology in social studies classrooms, such as the following:

- How has the Internet changed the way in which elected officials campaign and fundraise, and is there a new role for the influence of money in politics?

- Does WikiLeaks make a better and more transparent government, or does it compromise national security and individual privacy?

- How did Twitter apparently influence popular uprisings and topple governments during the Arab Spring (which, coincidentally, took place during the spring semester in which this class was taught), if other reports said that repressive governments had shut down the Internet and cell phone use in their countries?

On the other hand, the literacy TCs appeared to need to learn how to use social media to write more creatively and in greater consistency with standard English.

Consistent engagement and exploration of such topics are needed to assist faculty members and TCs in evaluating the use of technology in the social studies classroom. In addition to varying degrees of literacy and content specific considerations, we also had to develop protocols and systems for addressing technology-based challenges. As implemented, the project had some challenges but also revealed promise and a number of lessons learned.

Additionally, faculty training on the available technologies and their classroom functions and applications will be required. This effort also revealed that instructors who had less familiarity with the new media were reluctant to fully engage in its use and, as a result, ended up seeing less of an impact on their teaching. Similarly, some TCs took the lead online while others needed more direction on how these activities fit into the typical course script.

The pilot implementation of this project has several implications for teacher educators working collaboratively to integrate social media to teach content. First, as a starting point, it is essential to conduct a technology awareness assessment of all team members prior to beginning the project. This assessment will assist all faculty collaborators in understanding the tools. Once this baseline is established, structured opportunities to share resources should be scheduled.

Additionally, project members should develop a common assessment criteria and accountability measures across courses and content areas. Faculty members can then examine key variables that are influencing writing regardless of the content area focus. Having weekly technology sessions that allow team members to introduce new technologies and teaching tools to each other are also useful.

The W4YL Project gave TCs an opportunity to implement, discuss, critique, and reflect thoughtfully upon ways to use old and new literacies to teach writing and content area literacy. In this regard, the test of the selected strategies yielded valuable information with implications for the future development of technology-based teaching processes for the writing development of teacher candidates and their pupils. We plan to redesign and refine this process for further implementation in the future.

References

Barnard, I., Collier, S., Duprez, D., Sheld, S., & Stallcup, J. (2009). TNE literacy research project, Year 3. Retrieved from California State University, Northridge, Data Warehouse: http://www.csun.edu/~tnesrc/documents/WritingProjectReport.pdf

Calkins, L. (1994). The art of teaching writing. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Collins, A., & Halverson, R. (2009). Rethinking education in the age of technology: The digital revolution and the schools. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Creswell, J., & Clark, V. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Foley, B. (2012). Identities unleashed. In C. C. Ching, & B. J. Foley (Eds.). Technology and identity: Research and reflections on life in a wired world. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Grisham, D.L., & Wolsey, T.D. (2011). Writing instruction for teacher candidates: Strengthening a weak curricular area. Literacy Research and Instruction 50(4),348-364.

Hobbs, R. (2011). Keynote empowering learners with digital and media literacy. Knowledge Quest, 39(5), 13-17.

Jenkins, H. (2009). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st century. Chicago, IL: MIT Press.

Judson, E. (2010). Improving technology literacy: Does it open doors to traditional content?. Educational Technology Research and Development, 58(3), 341-58.

Kajder, S. (2007). Bringing new literacies into the content area literacy methods course. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 7(2), 92-99. Retrieved from https://citejournal.org/vol7/iss2/general/article3.cfm

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2003). New literacies: Changing knowledge and classroom practice. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2011). New literacies: Everyday practices and social learning.New York, NY: Open University Press.

Larson, L. (2009). Reader response meets new literacies: Empowering readers in online learning communities. The Reading Teacher, 62(8), 638-48.

Luce-Kapler, R. (2007). Radical change and wikis: Teaching new literacies. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 51(3), 214-23.

Merchant, G. (2010). 3D virtual worlds as environments for literacy learning. Educational Research, 52(2), 135-50.

National Council for Teachers of English. (2004). NCTE beliefs about teaching writing. Retrieved from http://www.ncte.org/positions/statements/writingbeliefs

New London Group. (1996). The pedagogy of multiple literacies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60-92.

New London Group. (2000). A pedagogy of multiple literacies: Designing social futures. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.). Multiple literacies: Literacy learning and designing social futures (pp. 9-38). New York, NY: Routledge.

Silverman, D. (2009). Doing qualitative research (3rd ed.). London, UK: Sage.

Street, C. (2003). Pre-service teacher’s attitudes about writing and learning to teach writing. Teacher Education Quarterly, 30(3), 33-50.

Street, C., & Stang, K.K. (2008). Improving the teaching of writing across the curriculum. A model for teaching in-service secondary teachers to write. Action in Teacher Education, 30(1), 37-49.

Sweeny, S. (2010). Writing for the instant messaging and text messaging generation: Using new literacies to support writing instruction. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 54(2), 121-30.

Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (2009). Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Wesch, M. (2009). From knowledgeable to knowledge-able: Learning in new media environments. Retrieved from http://www.academiccommons.org/?s=From+knowledgeable+to+knowledge-able%3A+Learning+in+new+media+environments

Whitin, P. E. (2009). Tech-to-stretch: Expanding possibilities for literature response. The Reading Teacher, 62(5), 408.

Wilder, H., & Mongillo, G. (2007). Improving expository writing skills in an on-line teaching environment. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 4(1), 47-498.

Wolsey, T., & Grisham, D. (2007). Adolescents and new literacies: Writing engagement. Action in Teacher Education, 29(2), 29-38.

Author Notes

Shartriya Collier

Elementary Education

California State University, Northridge

Email: [email protected]

Brian Foley

Secondary Education

California State University, Northridge

Email: [email protected]

David Moguel

Secondary Education

California State University, Northridge

Email: [email protected]

Ian Barnard

English Department

California State University, Northridge

Email: [email protected]

Appendix

Text from Figures

Text from Figure 1:

Write For Your Life

W4YL is built upon the philosophy that stories, articles, and writing topics come from our daily life experiences in our communities and the world around us. Essentially, your charge is to write as often and as much as possible. Writers become good writers by writing and writing often (Calkins, 1994).

As teachers you need to learn about many forms of writing – and there is no better way to learn than to practice it. This site provides an opportunity to explore how to use blogs, twitter, forums and messaging in a school context.

Learn more about W4YL

You will need to create an account and select the group for your class. Then go to “My Groups” to find out what to do. Other things you can do on the site:

- change your profile and add an image

- update your status (in profile)

- connect your twitter account

- post to your blog

- talk to people in chat

Peer Conferencing: The Heart of the Writing Workshop

Lucy Calkins often states that “writing is a personal and interpersonal” endeavor. In other words, simply listening, reading, and relating to our peers allows us to have insights and perspectives on a topic that we may not have thought about in the past. Often times, people tend to believe that they are alone or that they are the only ones to have experienced extreme joy, pain, love, loss, and/or happiness. However, when we share our writing we often learn the people are not as different from each other as many of us think. As a matter of fact, when we share our writing, we are often inspired by others.The goal of peer conferencing is to allow students

Text from Figure 4:

Dr. Collier’s blog

Post new blog entry.

Teachers Working for Community Change: The Power of Volunteering

Several weeks ago, I volunteered at the Los Angeles Food bank. We worked in an assembly line fashion bagging cereal, juice and other products for homeless women and families throughout Los Angeles.

While most people’s ideal Saturday morning does not consist of waking up and volunteering for 4 hours, you would be surprised by the amazing feeling you get by knowing that you are actively helping to make a difference in the world. I believe teachers are not only educators in the classroom, we are educators in all areas of life. We show our students what is means to be an active citizen, what it means to stand for a cause you believe in. So this week, I encourage you, get out there, touch the world, both in and outside the classroom.

If anyone is interested in volunteering on a Saturday morning, let me know!

Los Angeles Food Bank

http://www.lafoodbank.org/

Downtown women’s Center

http://www.dwcweb.org/

Text from Figure 5:

Narrative Writing Module

Write For Your Life

Module Two

Narrative Writing: Fun with Characterization

Submitted by lizoo331 on Mon, 05/16/2011 – 14:39.

My favorite character

My favorite character is Bell from Disney movie, The Beauty and The Beast. She has a beautiful face as well as a beautiful voice. I love her singing voice. I like how she’s not like any other princesses who have pretty face and always meet prince charming. Bell has not only pretty face but also intelligent by reading a lot of books. She also has such a kind heart that would be able to love the Beast.

Text from Figure 6:

lucyi215’s blog

Blogs in my classroom

In my classroom I would use many blogs for my students to practice writing, This way they do not have to be graded for what they are writing. There is not a specific length, and I do not want students to feel obligated to write. They can choose their own topics and write what they feel. I would have them do at least one a week and would reinforce it until they become used to writing without me prompting them to do so. Students also find it much more enjoyable to type things, rather than to sit down and write a story with a paper and a pen. I would have students come up with their own blog page, design it, maybe have a theme. This will be a great use of technology inside my classroom. This is just like keeping a virtual journal.

Tompkins states “Children use journals to record personal experiences, explore reactions and interpretations to books they read and videos they view, and record and analyze information about literature writing, and social studies and science topics.” Sometimes these journals are the only way students get to express their feelings and talk about what is bothering them.

Some challenges I might face are assigning students to visit their blog for homework. Not all children have access to a computer at home. In order to fix this problem I would set up a weekly appointment at the computer lab of my school so my students can go onto their blog at least once a week.

A letter to myself….10 years from now!

To: Me, myself and I- Dr. Inedzhyan,

I am now 34 years old. I have a beautiful family, my husband is in the medical field and my three children are beautiful, I have two girls and a boy, McKenzie, Audrey and Andy. Audrey and Andy are paternal twins. Being a principal in an elementary school is great,

Text from Figure 7:

maryqt’s blog

Women Clean while Men Dream

Do you ever wonder why Febreeze and laundry detergent commercials such as Tide and Gain typically show women spraying the couches and doing the laundry? Or why most sports related commercials such as Nike or fitness products show men as the characters involved in the sport? The answer lies within our own social standards. It is women that most people expect to perform house related chores and it is men that are usually expected to be involved in athletic sports. Stereotypical gender roles have been created by our own social standards; however, the media plays a vast role in the advocacy and the sheltering of stereotypical gender roles through their depiction of men and women roles via commercials, magazines, movies, sitcoms or anything related to the media. The media is a major influencing factor in gender socialization thus, controls and affects the way many people view the opposite sex and what is expected from them.

My Daddy….

I vividly remember him in my life but when he was in it my world was complete and wonderful. He was a puzzle to me. He seemed so busy and occupied with other things that I quite could not grasp. However, when we made eye contact he would instantly let me know what I was and what I meant to him. I was Daddy’s little girl. I was the apple of his eye. I was his trophy, his jewel, his pride. The only pure and precious thing that he knew and he could call his own. But why did I see my mother cry so much? Why did it seem as if she was living a life of misery and bitterness at his cost? Why was he a mystery to me and how could a daddy be a mystery to his daughter? I could not understand what was happening. It was beyond my reach, beyond my mental capacity, beyond my maturity level.

![]()