Project Overview

In many developed countries, including Ireland, low literacy levels among young people from socioeconomically disadvantaged communities continue to be a serious concern. Studies of reading literacy in primary schools of designated disadvantaged status in Ireland indicate that almost one third of pupils in these schools have serious reading difficulties (Department of Education and Science Inspectorate, 2005; Eivers, Shiel, & Shortt, 2004). Eivers, Shiels, Perkins, and Cosgrove (2005) also reported that approximately a quarter of pupils in these schools have between zero and 10 books in their home and that over one fifth of pupils at each grade level had been read to no more than a few times a month prior to starting school. This suggests that reading is not part of the cultural practice of these children outside of school but is instead an instructed process that takes place in school.

The Liberties area of Dublin city in Ireland represents one of the most socially disadvantaged areas in Dublin. The Diageo Liberties Learning Initiative (DLLI) is a state sponsored initiative established in the Liberties, among the primary aims of which is to improve literacy levels among school children through using digital media (Digital Hub Development Agency Act, § 8, 2003; the Diageo corporation has contributed €2.6 million toward establishing the DLLI; see http://www.diageo.ie/community/communityinitiatives/DLLI). The initiative involves introducing a range of digital projects into schools in the Liberties catchment area. Schools participate in these projects on a voluntary basis. The Online Digital Video Book Review Project was one of the projects introduced to schools as part of the DLLI.

The Online Digital Video Project involved children creating book reviews based on their independent reading. Having read a book, a child drafted a book review. The child was then filmed presenting the book review, and the video created was uploaded to the project website. The collected book reviews formed a password protected online Digital Video Book Review Catalogue, which was accessible to the schools involved. This online catalogue provided a resource where teachers and children within the project could watch other children’s book reviews and find books that they might like to read. In this way children might be encouraged and motivated to read for pleasure.

Six primary schools took part in the project, and two classes from each school participated. Children from infant level (4/5 years) up to sixth class (11/12 years) across the participating schools completed digital video book reviews. The project was carried out over a 4-month period, and almost 100 book reviews were uploaded to the website.

How It Worked: Technical Overview

The schools were given an Apple Media Kit to enable the creation of the online digital video book reviews. This equipment, known as the James Bond Kit, consisted of a silver metal briefcase, a G4 iBook, an iSight video camera, a Canon DV camera, and a Canon Ixus still camera (2 MP). The book reviews were recorded using iMovie and the external iSight Web camera. However the latest version of the Apple computers and laptops contain an inbuilt webcam, thus eliminating the need for the external iSight camera.

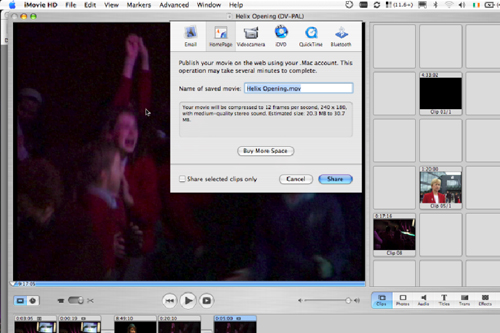

To record a book review, the users positioned themselves in front of the camera and pressed the record button in iMovie when they were ready to begin speaking. Once recorded, the performance could be reviewed. If users were not satisfied with their recording, they could simply rerecord the performance. Having satisfactorily recorded the presentation, users clicked File, Share, Home Page, which opened a home page dialogue box, where users could give the video clip a name (see Figure 1). They then clicked Share, and iMovie automatically compressed the movie before opening a .mac account, which was a password protected site set up by the project director. When the site opened, users were presented with three categories:

- Group One (5-7 year olds)

- Group Two (8-10 year olds)

- Group Three (11-12 year olds)

Figure 1. Select Homepage. Give movie a title. Click Share.

Users then selected the category of choice. In an effort to maintain consistency of design across the site, the project director asked each user to select “Frameless Large (black)” from the selection of options provided in the dialogue box (see Figure 2). Once a frame was selected, a new webpage opened, where users were asked for additional information about the book and the author. When this information was provided, users clicked on the Publish icon, and the book review was uploaded (see Figure 3).

Figure 2. Select category. Select “Frameless Large (Black).”

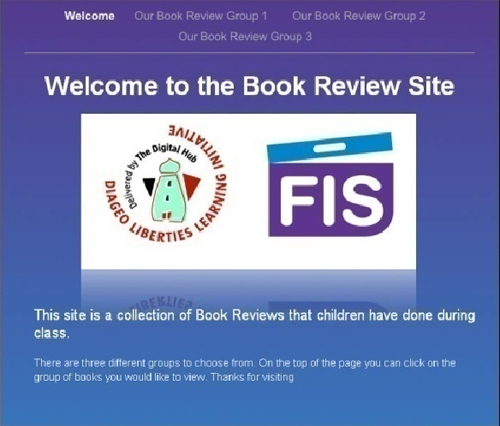

Figure 3. The Online Book Review homepage.

The collected book reviews formed a password protected Online Digital Video Book Review Catalogue, which was accessible only to the schools participating in this project. This catalogue provided a resource where teachers and children within the project could download and watch the book reviews and find books they might like to read. Figures 4 and 5 illustrate book categories as they were presented in the online catalogue.

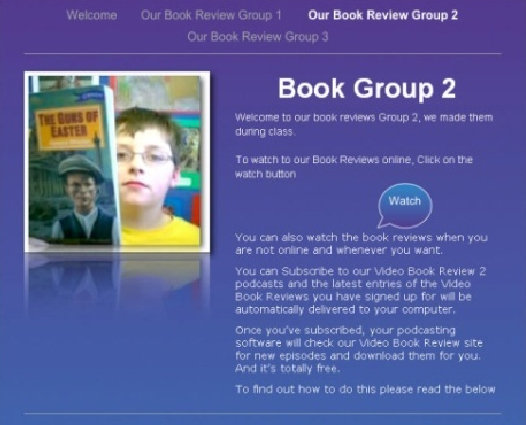

Figure 4. Introduction to Group 2.

Figure 4. Introduction to Group 2.

Figure 5. Book Reviews in Group 2.

Figure 5. Book Reviews in Group 2.

Technical support was provided by the project director in the form of a detailed, illustrated, step-by-step self-help guide. He was also contactable by phone and short message service (SMS).

Background and Context to the Online Book Review Project

The background to this project lies in the larger FÍS project (www.fis.ie). FÍS (literally translated from Gaelic as vision) is an initiative from the Department of Education and Science (DES) in the Republic of Ireland and is managed by the National Film School at the Dun Laoghaire Institute of Art, Design and Technology. It was designed to introduce the medium of film into classrooms as a support to the Irish Primary School Curriculum (National Council for Curriculum and Assessment, 1999). The association of film as an art form and the utilization of digital technologies are also seen to complement the work of the National Centre for Technology in Education. Launched in 2000 in 28 schools geographically dispersed across Ireland, the FÍS project was expanded in 2003 to include 50 schools in the second phase of the project (2003-2006). This phase, which was known as Fís II, was facilitated and managed through the DLLI (http://www.fis.ie/default.asp?PageName=AboutFisADo).

The overarching aim of the FÍS project is to explore film as a means of learning. The project is linked primarily with the emphasis in the Primary School Curriculum on the exploration of creativity and self-expression through the visual arts, drama, music, dance, and literature (DES, 2000). It is both a child-centered activity and a teacher-directed, interest-driven process. It seeks to engage teachers and pupils in cooperative exploration of film appreciation and film-making in a productive and educationally enhancing creative classroom climate. The FÍS Project uses a wide range of learning experiences, including creative work, acquisition of new skills and techniques, problem solving, independent work, communication skills, use of new materials, firsthand experience of the arts, language learning, collaborative activity, and self-expression (DES, 2000).

Among the recommendations of the evaluation of Phase 1 of the FÍS Project (McNamara & Griffen, 2003) was that further implementation of FÍS should involve greater emphasis on curriculum integration and everyday use with “much less emphasis on ‘big’ projects trying to lead to impressive ‘products’” (McNamara & Griffen, 2003, p. 56). It also suggested that teacher professional development should focus more on pedagogy and curriculum integration, emphasising plans, projects, ideas, and so on to open possibilities for teachers to integrate FÍS into regular classroom practice rather than set pieces or once-off projects. It was against this backdrop that the current book review project evolved. The original idea of having a video diary of the children’s personal book reviews evolved during a brainstorming session with a group of primary school teachers from the DLLI. This idea was then further expanded to include the development of an online Digital Video Book Review Catalogue.

Book Reviews: What the Literature Says

Although frequent independent reading is believed to be an important component of reading literacy achievement, studies have consistently shown that many children do not frequently read independently (Reinking & Watkins, 2000). The volume and diversity of students’ independent reading are viewed as central to improving children’s reading ability and to engaging them in reading for pleasure (Alverman & Guthri, 1993; Morrow, 1991; Postlethwaite & Ross, 1992; Stanovich, 1986). Also, strong positive correlations exist between reading achievement and the amount of children’s independent reading (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2004; Postlethwaite & Ross, 1992; Reinking & Watkins, 2000). For example, student independent reading has been demonstrated to increase proficiency in vocabulary and reading comprehension (Guthrie, Schafer, & Huang, 2001).

Book reviews are essentially reviews completed by pupils after they have read a book independently. Its purposes are to encourage children to read more, to read more widely (for example, to read across genres and topics), and to write for an audience (Reinking & Watkins, 2000). Reviewing the book involves summarizing, synthesizing, analyzing and evaluating the ideas and characters in a book (Allington, 2005). However, longstanding evidence shows that children generally dislike writing book reviews and that book reviews tend to represent writing and responding to literature in ways that require low personal involvement, thus discouraging engagement and risk taking (Reinking & Watkins, 2000).

Creating online book reviews has the potential to reconceptualize the notion of the conventional book review and to engage pupils positively in meaningful communicative experiences. Unlike conventional book reviews, which are generally written only for the teacher, the online book reviews in this study were shared by a larger audience that included children, teachers, and parents from within the DLLI community. There is much research to suggest that motivation and enthusiasm to write increase when children perceive an audience beyond their teacher (enGuage Resources, 2003; Sperling & Ylvisaker, 1989).

In terms of the writing process, Graves (1994) argued that writing is a social act that is meant to be shared with others. He also suggested that the extension of the audience beyond the immediate peer group encourages ownership and pride in writing. Similarly, Calkins (1994) suggested that publishing should be celebrated. Publishing work on the Internet can, therefore, be viewed as a way to motivate children to write, extend their audience, and celebrate their publications. Indeed Karchmer (2008) found that primary school children’s motivation to produce higher quality written work increased when they knew it was to be published on the Internet. In addition, the context of presenting the children’s own book reviews on film is an exciting and novel way to publish children’s work and may further increase motivation to engage in purposeful writing.

Writing skills can then be taught within the meaningful context of the online book review. In this way children move from “knowledge telling” to “knowledge transforming,” as they modify and develop their writing to communicate more effectively with their audience (Scardamalia & Bereiter, 1986).

The process of filming a book review also reinforces the notion of reading and writing as complementary skills. However, a digital video book review is not solely dependent on the written word. A child is not dependent on producing a well-crafted written draft in order to present it to the camera. Children can craft their reviews solely through the medium of speech, or they can draft written notes to support their oral presentations. This flexibility is particularly significant for the struggling writer or for the learner who is more comfortable with the oral medium rather than written expression.

Finally, the project website through which pupils and teachers in the DLLI can access the completed book reviews is a complementary aspect of the Online Digital Video Book Project. The website provides a resource where children in the DLLI can become aware of one another’s reading and to find books they too might like to read, thus stimulating further reading. The website also has value as a teaching tool in that it can be used as a vehicle for critical appraisal of the book reviews and the further development of book reviewing skills. Researchers, Bridge, Compton, Hall, and Cantrell (1987) found that as a result of an increase in peer and teacher conferencing, students were more likely to revise their writing in response to feedback received. It is also likely that as a result of peer and teacher discussion about the online book reviews, the quality of the book reviews will further improve. Moreover, the online book review can be used a starting point for critical discussion about books the children have read. This is particularly significant if a number of children have read the same book. Research has shown that opportunities to engage in discussion are related to improved achievement (Applebee, 2003, as cited in Allington, 2005).

Format of Pilot Study

This pilot study was carried out to establish if the online digital book review project was a viable model for the classroom from both operational and pedagogical points of view. The study was initially planned to be carried out over a 6-week period, but this period was extended to 4 months (a school term). A number of reasons supported this extension. Some schools were slow to get started while others had technical difficulties that took time to solve. A 6-week timeframe was inadequate to establish the pedagogical impact of the project, in particular, the usefulness of the online catalog. Finally, we needed to establish whether the project was sustainable.

Data generation and analysis involved three sources of data: (a) formal and informal interviews with the FÍS project manager, participating teachers, and pupils, (b) teacher survey, and (c) observation of pupils as they presented their reviews on film. All schools were visited at the beginning of the study, and the teachers participating in the project were interviewed informally. The purpose of this interview was to ascertain the teachers’ understandings of the book review project and how they intended to organize the project within their own school setting.

We then selected two schools, which we intended to visit as participant observers on a weekly basis. Selection of these schools was based on their understanding of the online book review process as an integral part of their English (language arts) curriculum rather than a once-off experience for the children.

The first of these schools was visited weekly for the 4-month duration of the project. However, the second school experienced many technical problems. As a result it was only possible to visit on two occasions (once at the beginning of the project and once at the end). In both schools, we observed the children recording their book reviews. We discussed the reviews with the children, and as they filmed their book review we asked them to describe and explain what they were doing. We also held informal discussions with the teacher on each visit and formally interviewed them on completion of the project. This process generated data on experiences of and reflections on the project.

Informal interviews were also held with the project manager on a weekly basis throughout the project, and an open-ended questionnaire was sent to all participating teachers at the end of the project. The survey contained three discrete sections: the Digital Book Review Project in action, operational and technical issues, and pedagogical issues. These sections were decided upon as a result of the review of literature and initial analysis of the fieldnotes and interview transcripts. There was a 100% response rate to the survey.

A typological analysis framework, outlined by Hatch (2002) was adopted initially for data analysis. A salient feature of this framework is that data analysis starts by dividing the complete data set into categories based on predetermined typologies. The main themes of the interview schedules and the teacher survey formed natural frameworks for generating typologies, and initial data processing took place within these categories.

Hatch believed that typological analysis can be problematic for observational data given the nature of such data and that starting analysis with predetermined categories can lead to a more positivist than qualitative analysis and that crucial data might be ignored. However, we tried to avoid this pitfall by re-examining the categories after coding the data. We could, thus, ascertain whether the categories were justified by the data or if the data not coded contained insights that were contrary to what was proposed. Overall, decisions were driven by the data and, where necessary, new categories of adjustment added. This iterative process of sifting, analyzing, and winnowing a collection of data helped reduce it to a small set of themes that then lent themselves to the final narrative (as described by Cresswell, 2007).

Findings

As the pilot study was carried out to establish if the online digital book review project was a viable model for the classroom from both operational and pedagogical points of view, a number of operational and pedagogical issues emerged from data analysis that warrant discussion.

Operational Issues

Access to adequate and appropriate hardware, such as computers and digital cameras, is crucial to teachers’ effective use of and integration of technology into their practice; without enough of the right hardware they can come up against real learning barriers (Ertmer, 1999; Jones, 2004). Although the teachers in this study had been provided with adequate and appropriate software, operational issues arose in relation to the technical operation of the project, classroom management, and classroom organization. However, teachers and pupils alike found the equipment easy to use.

Using the Equipment: Recording

The teachers and children generally found the Apple operating system easy to use. In all the schools, the children operated the recording equipment themselves. Once shown, the children appeared to find the equipment easy to operate. All the teachers commented on the simplicity of the system. As one teacher explained, “They just had one button to press to start and then again to stop” (Questionnaire Teacher 3, May 2006).

In three schools the teacher modelled the process for the children before handing over control to the children. In the other three, the teacher showed a small number of children how to operate the equipment, and these children in turn taught and helped the other children. Three of the teachers stated that allowing the children to do the recording themselves gave them control and ownership of the project.

Figure 6. Child recording a book review.

Figure 6. Child recording a book review.

Technical Operation

The location of the equipment for the recording of the online book review proved problematic in that a number of teachers were forced to locate the kit away from the main classroom. In four of the schools, children recorded their book reviews in places such as the computer room, the library, or an infrequently used room. The primary reason given for this decision was the need for quietness to record. It appeared that the microphone picked up background noise while children recorded their reviews. Sending children away from the main classroom gave rise to supervision concerns, and adult help was required for this purpose.

It’s hard to do it in the classroom….There’d be talking and noise….You need somewhere quiet…and you don’t want to be outside with a child and the rest of the guys in here not being supervised. (Interview Teacher 1, March 2006)

I couldn’t have managed without help. (Questionnaire Teacher 4, May 2006)

Two schools persisted in carrying out the recording in the classroom. Despite the need for silence during recording, both teachers had the equipment set up in the classroom, because they found this arrangement easier to access and monitor. However, both commented on the difficulty of keeping the rest of the class quiet while the children recorded their reviews.

Using the Equipment: Exporting the Book Reviews to the Web

Five of the schools succeeded in exporting all of their finished book reviews to the Web. Apart from the initial difficulty, all of these teachers said the process was easy once they had mastered it. In all but one school where a number of the sixth-class children learned how to export, the teachers completed this process themselves. Three of the teachers commented on the time taken to export the reviews, telling us that “it can take seven or eight minutes to export a review” (Questionnaire Teacher 5, May 2006). This was compounded on occasion when there were a number of projects to be exported. The teachers generally tended to export the reviews out of school hours as a result.

One of the schools could not export the reviews due to technical difficulties. This school had persistent difficulty with connectivity to the Internet, and the teacher felt that this difficulty impeded the progress of the whole project (Interview Teacher 1, March 2006).

Classroom Organization and Time Management

In light of the difficulties found with respect to the technical operation of the project, it is not surprising that the issues of classroom organization and time management was a concern across all the schools. However, rather than presenting these issues as barriers to participation, the teachers came up with a number of ways of surmounting them, including

- Eliciting the help of other teachers in the school (such as the intercultural teacher or resource teacher),

- Filming the reviews before the formal start of the day or after the infant class had gone home (the infant classes have a shorter school day than the older classes), and

- Formally building the “book review” process into the regular class timetable.

This process was described by one teacher as follows:

I used the time when the children were at drama or choir initially, and we went to one of the quiet resource rooms to do the filming. Second time round, I set up the equipment in the quiet room and the guys did the filming themselves….I was able to keep an eye on them [from the base classroom]. (Interview Teacher 1, March 2006)

Technical Support

The technical support provided by the project director was cited by all the teachers as a major factor toward the successful completion of the project. He made onsite visits and was always available by SMS and phone. He also compiled a step-by-step guide, complete with photographs illustrating the entire process from beginning to end, which was found to be particularly useful. For example, Teacher 1 said, “The step-by-step idiot guide that Ciarán did, complete with photographs. What you’d see on the screen was fantastic” (Interview, March 2006).

Summary and Implications

Overall the system was perceived as easy to operate, although the location of the equipment was somewhat problematic and gave rise to some supervision issues. The creative classroom organisation and time management strategies devised by a number of teachers provided a number of possible solutions. These strategies warrant discussion and sharing among the group of teachers involved in the project.

Second, concern regarding the time-consuming nature of exporting the reviews to the Web could be alleviated by exporting the reviews as they were completed. Time for this task needs to be built into the regular class timetable. The process likely will not be such an issue in the future, since the teachers have now mastered the uploading procedure. It is also feasible that the children could upload the completed reviews themselves. Class leaders could be appointed to help out if necessary. Internet access issues and speed of connection is another issue that needs to be addressed if teachers are to be encouraged to upload completed book reviews to the Web.

Finally, while the level of support provided was laudable, it is difficult to see how one person can maintain this level of support if the project is extended. Other means of support need to be considered. Technical problems, in particular, need to be addressed within a short timeframe. Teachers and children get discouraged and are unlikely to continue to engage in filming book reviews if they cannot upload them to the website due to technical glitches.

A number of pedagogical issues also arose for discussion. These included planning for and writing book reviews, the perceived pedagogical impact of the project, reflecting on the book reviews, and using the online catalogue.

Planning and Writing Book Reviews

The book reviews were constructed in all the schools using a process approach. As such, they were planned, drafted, redrafted, and edited. Teacher conferencing was an integral part of this process. In most cases headings were provided for the review and were along the lines of author, genre, plot, favorite/least favorite part, characters, setting, and rating. The children had the freedom to add their own headings if they wished. These written drafts formed the basis for the oral review.

I give some of the headings for the review to the children, and they add their own if they wish. They write the reviews themselves, and I correct them and talk with them about the ways in which they could improve on the review. The children practice reading out and presenting the review loudly and clearly before actually doing it. (Questionnaire Teacher 6, 2006)

In five of the six schools the children read their written reviews aloud or at least placed the written review in front of them as a crutch. In most cases they are to be observed reading these reviews. In the other school, the children were helped to make cue cards that contained key points and that “encouraged them to speak more slowly…get [their] thoughts more coherent…[make] less use of the famous ‘thing’ word” (Questionnaire Teacher 3, 2006).

The Development of Presentation Skills

The teachers uniformly reported that the project impacted most positively on the children’s presentation skills. However, we found that this did not happen automatically but was a gradual process and involved a lot of practice, focusing initially on speaking loudly, clearly, and slowly and then on the use of facial and vocal expression. Teachers approached this practice in different ways. Although some practiced away from camera prior to recording, the majority allowed the children to record themselves, then discuss the performance with the teacher or a small group of children, and rerecord in light of this discussion.

A number of the teachers commented on how nervous the children became in front of the camera and that it took a number of attempts to lessen the anxiety. One teacher also commented on how critical the children were of their performance, with some children recording their review eight or nine times before they were satisfied. Another described how the process enabled the children to be self-critical:

This means they can be self-critical….They can see themselves so even if nobody else said to them, “What do you think of that?”….They can see, “I was tongue tied there ..that was too rushed.”…They can be self-critical rather than it always being external. (Questionnaire Teacher 4, May 2006)

Observations of the project in action confirmed these teacher comments. Observers noted that children became nervous the first time they recorded a review. Although children each identified the camera as the cause of their discomfort, they found it difficult to articulate why. An awareness of the wider audience likely was at least partly responsible, judging from the following responses:

- “It’s like singing! You don’t be nervous and then when you go on stage you are!” (Fieldnotes School 2, February 6, 2006)

- “Other people are watching you on camera doing the review….It is kind of nerve wrecking as well….You’d be afraid that they’d be laughing at you in other schools.” (Fieldnotes School 6, February 18, 2006)

The children recorded their review several times before they were satisfied with their efforts. One child, for example, made seven attempts to complete his review. Twice, he felt that his delivery was not good enough, and he decided to begin again. Twice he misread a word and decided to start again. Twice, someone came into the room, and he stopped. He lost his way once.

However, despite this tendency to rerecord, children’s initial presentation skills were limited. They tended to forget what to say, to place the book over their mouth, to stand too close or too far away from the camera, to speak too softly, to speak too quickly, and to speak without expression. The presentation skills improved over time, but only after sustained peer and adult feedback. The children believed initially that their reviews were “good” and said they were “proud” of their efforts (Fieldnotes, School 6, February 18, 2006). Not until they had appraised the book reviews as a class did they begin to take cognizance of their presentation skills, as illustrated in the following extract from the fieldnotes:

Once the reviews were uploaded the children were keen to show them to their classmates. The teacher accessed them through the project website on the class computer, and the children crowded eagerly around to see them. Robert’s was first. He stood to the side with his head bowed as the class watched his review. As it started to play, giggles broke out around the room. These were stifled and the children settled to watch. When it ended, a round of applause broke out and Robert smiled broadly.

Although the review was solely descriptive, rambling and had omitted key details, the children commented that “he tells you loads of information about the book” and that “he told story really well.” When the teacher asked if they had any advice they could give Robert as to how he could make his next online book review even better, the only response was that he could have included more detail. Prompting the children the teacher then asked if it was easy to hear him. It was not, so she asked what they could tell Robert so that it would be easier to hear him the next time. The responses included “talk louder” and “not to put the book over his face.” The teacher then modelled how placing a book in front of a speaker’s face could muffle sound and discussed with the children where they should hold the book when they were talking.

The rate of delivery in the next online book review shown was very fast. As part of the discussion on this review, it was remarked that “he talked too fast” and the need to speak slowly was noted. At the end of the lesson the teacher and pupils recapped on what they had learned about presenting their book reviews. This included to speak loudly and slowly and not to hold the book over your mouth. As I observed the children recording book reviews later that afternoon, they were clearly making an effort to take this advice on board. When reviewing their recordings they assessed them in terms of the rate of speech and volume. (Fieldnotes School 2, February 24, 2006)

Developing the Quality of the Book Reviews

In three schools the children completed more than one review. In one of these schools almost all the children had completed two reviews, while in the other two, the children had completed at least three reviews each. Teachers in these schools commented on the development of the quality of the content of the reviews over time, in particular, the language used by the children.

These teachers reported reflecting on the quality of the reviews with their students as a small group or whole class exercise. They watched the reviews together with the children and reflected on the important elements of a book review and the type of language to use, such as vocabulary and adjectives. According to one teacher, these reflective sessions “helped children to expand their vocabulary as they encountered many new words, particularly those used to describe the plot and the physical and personality traits of various characters” (Questionnaire, Teacher 6, May 2006).

Analysis of the first set of reviews uploaded by the children from these schools reveals that the reviews were primarily descriptive in nature. They briefly summarized the story plot and finished with a sentence such as, “I liked this book because…” Many children also failed to identify all of the key characters, the main events, and the sequence of the story. Additionally, the vocabulary used by the children was limited. Children generally used simple, commonplace nouns and a narrow range of verbs, which were often grammatically incorrect. Adjectives or adverbs were rarely used, as illustrated in the following extracts from these first reviews:

In Rabbit Trick, rabbit done a trick on elephant and hippo and he found bit of rope…and she told him to pull and he pulled, and the rope snapped and she goes, “Oh,” and she went down and says, “Who’s stronger than you elephant?” and he said “I’m stronger than you, hippo!” She was smarter but she wasn’t stronger. And then my favorite bit is where she did a trick on him.

This is Orka, the boy who hated balloons. One day there was a monster, and he found a balloon and he got it, and a voice said “thanks,” and the voice was Orka, and Orka went to a party..and…and…was bursting all the balloon, and then he got one that was Orka’s, and, eh, he gave it back, but Orka said keep it.

….and it [the car] still wouldn’t start, and then the fisherman came, and then he said that it was running out of petrol, and then everybody was late for school, and when Mr. Kool was making….and he made it on time…. It was good because it was funny.

(Extracts from the first set of digital book reviews completed by School 2, February 2006)

By leading the students through reflection and discussion, the teachers worked to improve the quality of the reviews. For example, the children who had completed these reviews watched their reviews in class along with their peers and their teacher. This teacher accessed the book review website through an interactive whiteboard, so that everyone could clearly see and hear the reviews. In a short discussion after each review, the children were encouraged to say what was good about each review and to make suggestions for improvement. The teacher then focused on the content of the review and posed a series of questions relating to plot, theme, and story characters. As she did so, she continuously strove to expand the children’s vocabulary by asking the children to provide words to describe various events and characters. The lesson was ended with a recap on how future book reviews could be improved (Fieldnotes, February 6 2006).

A significant learning event was observed in this school during one such reflective session. The conversation was quite bland until a particularly expressive and articulate review from another school was accidentally shown. This review was on the C.S. Lewis novel, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (see Video 1). The reviewer invited her listeners to “step inside the wonderful world of Narnia” and told them that

A significant learning event was observed in this school during one such reflective session. The conversation was quite bland until a particularly expressive and articulate review from another school was accidentally shown. This review was on the C.S. Lewis novel, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (see Video 1). The reviewer invited her listeners to “step inside the wonderful world of Narnia” and told them that

this amazing book is about four children called Peter, Susan and Edward and Lucy, the youngest. They are taken away to go to London to stay with the professor because of the war. In this huge house where they are staying—it’s absolutely huge, and I mean huge—there’s over 1,000 bedrooms and a million rooms!

After a brief summary of the introduction to the story, she continued,

So, she walked into the wardrobe and there was Narnia, covered in snow. She ran out and told Peter, and Peter told Susan, and Susan told Edward. They didn’t believe her at all! So, if you want to read this book, which I highly recommend you do, join these four children in their epic battle to save Narnia from the wicked witch. [Italics added]

Complete silence descended on the classroom as this review unfolded. The children followed every word, and when the review ended a boy exclaimed, “She’s good!” The children immediately compared it to their own efforts and were able to extract the elements that made “hers sound good!”

- “Because she wasn’t afraid like, like all of us were afraid, and we didn’t do it with expression and she did it with expression.”

- “She only told us a little bit of it, and we want to know all of it, so we can read it, and we can know what the rest of it is.”

- “The girl said she would recommend the book.”

- “She said what her favorite part was.”

- “She gave it a mark out of ten.”

(Fieldnotes School 2, February 20 2006)

The teacher reported an improvement in both the quality of the book reviews and in presentation skills during the following week. Indeed, a number of boys remarked that they had been practicing in the mirror since last week, “trying to put passion in it like that girl!” They were observed trying to be more expressive in their delivery and were noted using phrases such as “It is very funny…” “My favourite bit is…” and “I would give this book 10 out of 10” (Fieldnotes, February 27, 2006).

Although the range of nouns they used remained narrow, they included some adjectives to describe characters and events. For example, a review on Anne Frank described the room the Franks lived in as “very small and cramped.” When reviewing their work they were also observed making comments in relation to expression and the use of these phrases. For example, Sean said his “expression was good. I like it…expression and all. I gave it marks out of ten and said it was funny.” (Fieldnotes, February 27, 2006).

Finally, from a content point of view, the children’s summaries of the stories became slightly more coherent in these later reviews. Interestingly, each of the children told the story of the book

quite succinctly and included a beginning, middle, and end as they practiced their reviews. However, as they filmed their reviews, they each attempted to include more detail and this resulted in a less coherent story, although it was still an improvement on their previous efforts. (Fieldnotes, February 27, 2006)

Perceived Impact on Literacy

Due to the short duration of the project, measuring and analyzing any impact on the children’s literacy was not possible. However, comments from both teachers and children suggested that they perceived this type of project to have the potential to positively impact children’s literacy.

The teachers believed that the project was an exciting and motivating approach to book reviews and improving literacy. They provided a number of reasons for this, each of which warrants further investigation. First, they felt that it provided an authentic context to write a book review and stressed that because the children were presenting the review to an audience, particularly one with which they had personal relationships, they were motivated to work. One teacher told us, “They wanted their work to be good…. They were very aware that their friends from the area would be watching!” (Interview Teacher 2, March 2006). This teacher also mentioned that because the children “loved recording the book reviews, they are writing more book reviews, and that can only have a positive impact on their reading and writing” (Interview Teacher 2, March 2006).

Second, facilitating the children to represent their work orally rather than in written format was also perceived by three of the teachers as a means of facilitating those children who struggled with written text but who were stronger verbally in communicating and representing meaning. As one teacher stated, “It’s a good way in for children who are strong verbally but weak in literacy [reading and writing]” (Questionnaire Teacher 5, May 2006).

Each teacher also mentioned the potential for oral language development. For example, one teacher stated, “It was good for oral language….Helped to expand their vocabulary, as they encountered many new words, particularly those used to describe the plot and the physical and personality traits of various characters” (Questionnaire Teacher 6, 2006). Finally, two teachers believed that the project provided a forum for children’s views and experiences, something “which normally would not be given” (Questionnaire Teacher 3, May 2006).

The children reported that constructing book reviews in this way was more exciting and fun. They appeared to find the thoughts of other children watching their reviews both scary and appealing. Many children commented on how nervous they felt in front of the camera initially but how proud they were of their review: “It’s quite exciting. Being on the camera and seeing yourself on the computer!” (Fieldnotes School 6, February 18, 2006). Numerous children over the duration of the project also commented on their preferences to orally present their reviews instead of writing them. One boy explained that he “gave more detail on the camera ’cos [sic] it’s easier to explain in words than in writing!” (Fieldnotes School 6, March 6, 2006).

As stated, each of these comments and observation indicate the potential for projects such as the online book reviews for literacy development. Each of the points raised warrants further investigation as this project is expanded.

Using the Online Catalog

The objective of the website was to provide a catalogue of other children’s book reviews that teachers and children could download and watch and perhaps find books they might like to read. We found no evidence that the website was widely used in this way, although a number of children commented to us how useful the catalog might be:

- “People that aren’t very interested in reading the book review, they can just look at you saying it out like, so they’d get the gist of the book as well.” (Fieldnotes School 6, March 6 2006)

- “Listening to reviews from other schools would be good, ‘cause you can say, ‘That sounds good. I think I’ll get that…’” (Fieldnotes School 2, March 6 2006)

Summary and Implications

The Online Digital Book Review Project added an extra dimension to the construction of book reviews. Publishing online was clearly enjoyable and exciting for the children across all six schools. Writing was purposeful in the context of presenting their reviews on film, and indications are that oral and written language skills can be developed within this context.

Although the main learning that occurred across all schools in this pilot study was the development of presentation skills, it is interesting to note the improvement of the quality of the children’s book reviews in those schools where the children published at least three book reviews. It appears that the teachers in these schools were able to embed the development of critical analysis skills, as well as the development of the written and oral language skills of the children in the task of crafting a book review. It also suggests that the construction of online book reviews provides a meaningful way to teach these skills.

Finally, the lack of use of the online catalogue represents a lost opportunity. The interaction that occured around the novel, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe described earlier is a wonderful example of how it can be used as a learning tool. The comments from the children suggest that they would like to use it as a catalogue.

Conclusions and Recommendations for the Future

This study sought to ascertain if and how the concept of online book reviews might be used in Irish classrooms, particularly with regard to the operational and pedagogical issues associated with the process. Technically, the system was easy to operate, although children could be given more control over the exporting process, in particular. They could then have more ownership and control over the process as well as reduce the teacher’s workload. The short duration of the project was insufficient to assess impact on the children’s learning processes. However, indications are that sustained engagement with this means of creating and publishing book reviews could enhance motivation to read and motivation to construct a book review. More importantly, this tool could be used to develop the children’s presentation skills, in general, as well as the quality of their book reviews.

Some concerns must be addressed prior to adopting the online book review process with a larger community of learners. The project requirements need to be clear, and teachers need to be given the opportunity to discuss expected outcomes. It appeared from initial conversations with the teachers in this study that many were unclear of the project structure or objectives. For example, a number of schools perceived the project to be a one-time exercise, and their children completed just one book review each. Others saw it as an ongoing process embedded as part of their English language program. Findings from this pilot study suggest that an online book review project should not be conceived as a one-time project. The necessary skills are developmental and take time. Consequently, this type of book review project should roll out over the course of a school year, at least with the underlying plan of becoming an integral part of the curriculum. It would be appropriate to expect that children would complete, perhaps, three or four reviews per year.

A framework should be developed that provides ongoing opportunities for critical reflection for the teachers. For example, when the children had the opportunity to construct a number of book reviews, the focus of skills development moved along the trajectory from presentation skills to language and critical analysis skills. However, after the initial training the teachers had no opportunity to reconvene and discuss the learning they were witnessing in their classrooms and how they might extend this learning. Providing teachers with such opportunities to share their observations would empower teachers to articulate the learning processes they see in action. It would enable them to develop a common language to describe the learning they observed within their classrooms, as well as helping them devise appropriate alternative assessment tools for describing literacy.

Time also needs to be built into teacher professional development opportunities to discuss and share ideas and concerns about technical and classroom management issues, such as location of equipment and supervision.

Finally, although the level of technical support provided for the initial pilot project was laudable, one person would have difficulty maintaining this level of support, especially if the community extended. Other means of providing ongoing support need to be considered, and a realistic timeframe of response needs to be developed to circumvent teachers and children getting discouraged and disengaged from the process. A robust framework that provides for ongoing pedagogical and technical support would lead to the development of a self-sustaining community of learners who develop online book reviews, which contribute to defining what it means to be literate in the 21st century.

References

Allington, R. (2005). What really matters for struggling readers. Designing research based programs (2nd ed.), Boston MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Alvermann, D., & Gutherie, J. (1993). The national reading research centre. In A. Sweet & J. Anderson (Eds.), Reading research in the year 2000. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Applebee, A. (1991) Literature: Whose heritage? In E. Heibert, (Ed.), Literacy for a diverse society: Perspectives, practices, and policies (pp. 228-252). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Bridge, C., Compton-Hall, M., & Chambers Cantrell, S. (1987). Classroom writing practices revisited: The effects of statewide reform on writing instruction. The Elementary School Journal, 98(2), 151-169.

Calkins, L.M. (1994). The art of teaching writing. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Cresswell, J. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design – Choosing among five approaches. London, England: Sage.

Department of Education and Science. (2000) Draft FÍS project description. Dublin, Ireland: Author.

Department of Education & Science Inspectorate. (2005). Literacy and numeracy in disadvantaged schools (LANDS), Dublin, Ireland: Author.

Digital Hub Development Agency Act, §8 (2003).

Eivers, E., Shiel, G., & Shortt, F. (2004). Reading literacy in disadvantaged primary schools, Dublin, Ireland: Educational Research Centre.

Eivers, E., Shiel, G., Perkins, R., & Cosgrove, J. (2005). The 2004 national assessment of English reading [NAER], Dublin: Educational Research Centre.

Ertmer, P.A. (1999). Addressing first- and second-order barriers to change: Strategies for technology integration. Journal Educational Technology Research and Development, 47(4), pp ##s.

enGauge Resources. (2003). What works-enhancing the process of writing through technology: integrating research and best practice. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED479913)

Graves, D. (1994). A fresh look at writing. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Guthrie, J., Schafer, W., & Huang, C. (2001). Benefits of opportunity to read and balanced instruction on the NAEP. Journal of Educational Research, 96, 145-162.

Hatch, J. A. (2002). Doing qualitative research in educational settings. New York, NY: State University of New York Press.

Jones, A. (2004). A review of the research literature on barriers to the uptake of ICT by teachers. Coventry, UK: Becta.

Karchmer, R. (2008). The journey ahead: Thirteen teachers report how the Internet influences literacy and literacy instruction in their K-12 classrooms. In J. Coiro, M. Knobel, C. Lankshear, & D. Leu (Eds.), Handbook of research on new literacies (pp. 805-839). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

McNamara, G., & Griffen, S. (2003). Vision in the curriculum: An evaluation of the Fís project in primary schools in Ireland. Dublin, Ireland.

Morrow, L. (1991). Promoting voluntary reading. In J.Flood, J. Jenson, D.Lapp, & J.R. Squire (Eds.), Handbook of research on teaching the English language arts (pp. 529-535). New York, NY: McMillan.

National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. (1999). Primary school curriculum. Dublin, Ireland: Author.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2004). Learning for tomorrow’s world – First results from PISA 2003. Paris, France: OECD Publications.

Postlethwaite, T. N, & Ross K. N. (1992). Effective schools in reading: Implications for

educational planners. The Netherlands: IEA.

Reinking, D., & Watkins, J. (2000). A formative experiment investigating the use of multimedia book reviews to increase elementary students’ independent reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 35, 384-419.

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (1986). Research on teaching reading. In M. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed.) (pp 779-799). New York, NY: Macmillan.

Sperling, M., & Ylvisaker, M. (1989). The quarterly of the National Writing Project and the Center for the Study of Writing, 11(1-4). Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED316865)

Stanovich, K. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21, 360-407.

U.S. Department of Education. (1999). The NAEP 1998 writing report card for the nation and the states. Retrieved from National Center for Education Statistics website: http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/pubs/main1998/1999462.asp

Author Notes

In December 2009, the Fís Online Bookclub was launched nationwide in Ireland. To register, teachers simply log onto http://www.fis.ie/, click on “FlS BookClub,” and select “join your school up.”

Deirdre Butler

St Patrick’s College of Education, Dublin City University

Dublin, Ireland

Email: [email protected]

Margaret Leahy

St Patrick’s College of Education, Dublin City University

Dublin, Ireland

Email: [email protected]

Ciarán Mc Cormack

Institute of Art, Design and Technology

Dublin, Ireland

Email: ciaran.mccormack.iadt.ie

![]()