No one fits in a box. Not students, not teachers, not college students, not preservice teacher professors. Especially in authentic teaching contexts, we cannot expect anything less than complex interactions. This is the generative stuff: to be unsure of what to do in the face of severe inequities, and to remain in this space growing and learning anyway. (Sam, Preservice Teacher, Postcourse Interview)

What happens when teacher preparation moves outside the realm of college classrooms and into contextualized interactions with middle schoolers? This article describes lessons learned from a connected literacy education course where preservice teachers (PSTs) partnered with a local middle school to teach literacy actively through podcast and digital graphic novel creation. Specifically, we concentrate on the journey of the five teacher candidates who were asked to design after-school clubs that engaged youth in multimodal storytelling. Our research is rooted in reflections and analysis from the education professor, the partnering after-school director, and the five undergraduate PSTs enrolled in the course.

Future teachers need equity-focused, production-centered, interest-driven connected learning (Ito et al., 2013) and connected teaching opportunities (Mirra, 2017) that provide deliberate, scaffolded social support into the technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge necessary for integrating new media into classroom spaces (Mishra & Koehler, 2006).

By drawing on weekly PST v-log posts/comments on VoiceThread throughout their journey of facilitating after-school clubs and the final multimodal product that each group of PSTs produced, this paper illuminates the generative deterritorializations that a teacher education course steeped in connected learning/teaching principles produced.

Connected Learning in Teacher Education

In this piece, we theorize “the practice turn” (Ball & Cohen, 1999) in teacher education as working in synchrony with Connected Learning (Ito et al., 2013) and Connected Teaching (Mirra, 2017) models. Recent calls for improving teacher education for social justice have invoked the need for carefully crafted partnerships between coursework/field experiences, the university/K-12 settings, and professors/K-12 professionals (Darling-Hammond, 2006; Sanderson, 2016; Gelfuso, Parker, & Dennis, 2015; Waddell & Vartuli, 2015).

Horn and Campbell (2015) called such codesigned partnerships “mediated field experiences,” during which university instructors and partner teachers jointly worked to mentor PSTs, thus introducing “new forms of shared responsibility for preparing teachers among colleges and universities, schools, and local communities” (Zeichner, Payne, & Brayko, 2014, p. 2). These kinds of experiences have the greatest potential to “create disequilibrium and encourage candidates to think in new ways” (Zygmunt & Clark, 2016, p. 30).

Although connected learning (CL) approaches originated in K-12 landscapes, teacher educators are increasingly drawn to utilizing them in higher education for teacher preparation, as illustrated by the recent energy around the network using the hashtag #CLinTE (Connected Learning in Teacher Education; e.g., see Baker-Doyle, 2017). One component of the connected learning theories (Ito et al., 2013) that resonates with the teacher education literature is the notion that academic classrooms are just one node on a larger landscape of learning. While it is the norm that departments of education provide some form of field experiences in their classrooms, these field experiences are rarely central to a course design and almost never are truly coconstructed with school/community partners. Embedding connected learning principles into teacher education programs will naturally result in a commitment to designing courses with “broadened access to learning that is socially embedded, interest-driven, and oriented toward educational, economic, or political opportunity” (Ito et al., 2013, p. 4).

While a teacher education courses can be designed with the PST as the youth in the center, they can also be envisioned as a space to imagine or reimagine with PSTs the “what could be” (Damico & Rust, 2010) should they choose to integrate CL into their own future classroom. Reframed as more than curricula-enactors or test-givers, PSTs can begin to see their future identities as “environmental designers” who “craft the educational ecosystems in which we mutually learn and build with students” (Garcia, 2014, p. 7). In this way,

connected learning principles can provide a vocabulary for teachers to reclaim agency over what and how we best meet the individual needs of students in our classrooms. With learners as the focus, teachers can rely on connected learning as a way to pull back the curtain on how learning happens in schools and agitate the possibilities of classrooms today. (p. 7)

Connected teaching (CT) models can then be integrated into teacher education (Mirra, 2017). By carving out spaces in coursework for PSTs to engage in, not just CL principles in the coursework a professor designs but also CT practices they aid in designing and implementing, future teachers are more likely to confront the kinds of tensions and rewards that they will face when attempting to integrate this paradigm shift in the current reality of K-12 classrooms.

Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies

CL’s call to connect with communities is indelibly tied to issues of equity, as we also recognize the predominance of white teachers (both preservice and in-service) among schools that have high concentrations of students of color (Bloom, Peters, Margolin, & Fragnoli, 2015). Similarly our after-school clubs, facilitated by five white middle class PSTs to serve black students predominantly of lower socioeconomic status, served as a contact zone (Pratt, 1991) of sorts, a “social space where cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power” (p. 34).

Lisa Delpit (1988) used the term “culture of power” in her piece, “Teaching Other People’s Children” to understand how power dynamics between students of color and their predominantly white teachers operate within the space of the classroom (p. 282). According to Delpit, the “culture of power” is how people define the “codes or rules for participating in power” (p. 282). In her account, this culture is shifted and influenced by who holds the power in a culture of power. In the case of classrooms, this culture is inescapable. A particular dynamic of Delpit’s account becomes illuminated within the space of our after-school club: “Those with power are frequently least aware of — or least willing to acknowledge — its existence. Those with less power are often most aware of its existence” (p. 282).

The understanding of culturally sustaining pedagogy (CSP), coined by Django Paris (2012), thus informed the design and practices in our course, which will be discussed further in the context section of this piece. As Paris defined it, “Culturally sustaining pedagogy seeks to perpetuate and foster — to sustain — linguistic, literate, and cultural pluralism as part of the democratic project of schooling” (p. 93). Paris’ writings on CSP built from Gloria Ladson-Billing’s (1995) work on culturally responsive pedagogy (CRP), which she defined as a “pedagogy of opposition” resting on three criteria — “students must experience academic success,” “students must develop and/or maintain cultural competence,” and “students must develop a critical consciousness through which they challenge the status quo of the current social order” (p. 160). Importantly, CSP recognizes the intersectionality of each individual and community, reframing from essentializing particular groups of people (Paris & Alim, 2014).

Developing Teacher Identity

CL in teacher education is best accompanied by a nuanced understanding of teacher identity development. Rich work on the complexities around identities in both becoming (Britzman, 2003) and “unbecoming” (Sumara & Luce-Kapler, 1996) teachers helped us to make sense of the difficult negotiation of self and others that PSTs encountered during these authentic teaching/learning experiences.

Sumara and Luce-Kapler introduced three concepts of self-identity that help to expain the planes in which PST navigate their teaching experiences — the “pre-teaching image” that brings teachers to want to be educators, the ideal forms of themselves as educators, the “fictive image” developed while learning to teach, and the “lived image” that forms during student interactions in practice (p. 67). PSTs in this course lived in all three of these conceptual planes through their teaching experience, which generated sites of tension as these multiple identities clashed or contradicted each other.

The relationship the PSTs had with themselves as they navigated their identities as teachers, as students, as learners, and as professionals produced sites of contestation throughout the course. Britzman (2003) described this relationship as part of the development of ”private aspects of pedagogy,” which includes “coping with competing definitions of success and failure, and one’s own sense of vulnerability and credibility. Residing in the “heads” and “hearts” of teachers, and emerging from their personal and institutional biography, this “personal practical knowledge” is “knowledge made from the stuff of lived experience” (p. 28). This “private pedagogy” is triggered by “struggles between two kinds of ideological practice: concrete practice and symbolic practice … disjuncture between theory of and practice in the world” (p. 41). Preservice teachers effectively find themselves situated between two often discordant vantage points – that of the student and of the teacher (p. 36).

Trying on new identities naturally insinuates an automatic disassociation from other possible selves. Britzman cautioned that “becoming a teacher may mean becoming someone you are not. It is this dual struggle that works to construct the student teacher as the site of conflict” (p. 27). Allan (2004) similarly pointed out,

Learning to be a teacher is not a journey towards a fixed end, as denoted by the standards, but wanderings along a ‘moving horizon’ (Deleuze, 1994, p. xxi). As well as creating new knowledge, these wanderings provide opportunities for student teachers to establish, in Rose’s (1996) terms, new assemblages and new selves. (p. 425)

This incitement of wandering and uncertainty lingers long after a student teacher transitions into teacher, since

enacted in every pedagogy are the tensions between knowing and being, thought and action, theory and practice, knowledge and experience, the technical and the existential, the objective and the subjective … produced because of social interaction, subject to negotiation, consent, and circumstance, inscribed with power and desire, and always in the process of becoming. (Britzman, 2003, p. 26)

Clearly, then, not only PSTs are becoming. The complex world that teaching unearths makes novices of all educators. The movement from student teacher to teacher, however, is one that, perhaps more than any other phase, highlights these negotiations between practice (the concrete actions teachers take) and theory (the categorizations teachers leverage to make sense of their experiences; Britzman, 2003).

Deterritorialization

Finally, Deleuze and Guatarri’s (1987) rhizomatic wanderings into lines of flight, particularly deterritorialization, were useful in conceptually situating the myriad of moments when the five future teachers experienced surprise, tension, and ultimately, rupture between their previous frames of understanding as they were put in contact with authentic mentors, middle schoolers, and multimodal teaching/production literacy experiences.

Deleuze and Guattari (1987) introduced rhizomes as a more useful way of illustrating the unexpected, unpredictable, spouting nature of things: “all manners of becoming” (p. 21). In their conceptualization, ruptures, or broken/shattered “lines of flight” (brought about by deterritorialization) more accurately portray reality than more structural-linear representations. A rupture or line of flight instigates a deterritorialization, a sense of unfamiliarity and shifting.

Jackson and Mazzei (2012) described deterritorialization as the “process of un-coding habitual relations, experiences, and usages of language … that orients thought in a specific manner” (p. 89). Most importantly, this process of deterritorialization can “disrupt and open up contexts for other possibilities, disassemble unity and coherence, and break up hierarchies. … Deterritorializations are the breaks or flourishes that depart from expected ways of being/knowing/doing” (Kuby & Rucker, 2016, p. 35). This process of breaking down and disrupting previous constructions of self, other, and literacy allowed PSTs to reveal and develop new understandings.

Of course, everything deterritorialized quite naturally evolves to becoming reterritorialized, or familiar, again. Deleuze and Guattari (1987) said that deterritorialization holds the most possibility, however. They admonished their readers to “write, form a rhizome, increase your territory by deterritorialization, extend the line of flight to the point where it becomes an abstract machine covering the entire plane of consistency” (p. 11).

Allan (2004) powerfully took up deterritorialization as a frame in teacher education and wrote that “the function of the teacher educator, in Deleuzian terms, is to create pedagogical spaces which are open and smooth, in contrast with the closed and striated spaces of conventional approaches.” (p. 424). He added,

The rhizome is more than a metaphor for thinking about teaching; it is an instrument of flight which lives rather than represents. Instead of absorbing, and later replicating, content, student teachers [should] be involved in: “experimenting with pedagogy and recreating its own curricular place, identity, and content; expanding its syllabi and diversify its reading lists; supplementing educational discourse with other theories; deterritorializing theory of education from course based to interdisciplinary directions. (Gregoriou, 2002, p. 231, original emphasis). (p. 424)

This complex vision of teacher education puts much agency in the hands of the preservice teacher and rejects any one-size-fits-all notion about the messy enterprise of teaching and learning. It is no surprise, then, that we found rhizomatic theory as useful for illuminating the complex trajectory our PSTs traveled during the course of one very connected experience.

Methods

Context

The study took place during the spring semester of 2017, and it traces the journey of five PST participants who were enrolled in the second course in their literacy sequence at a very small (serving under 900 undergraduates) liberal arts college in the U.S. Deep South. (Note: All school and participant names in this piece are pseudonyms.) Middleton College markets itself as having an “across the street, around the globe” orientation toward teaching and learning and offers a host of community engaged learning experiences for its students. While Middleton is known as a progressive institution in a conservative state with deep ties to social justice, its student population (though increasing in diversity) does not reflect the predominant racial and socio-economic demographic, which in 2016 featured a population that was around 80% Black and with the per capita income averaging less than $25,000 a year.

Smithtown Public Charter School is a Title 1 school that was founded in 2015. At the time of this study, it served grades 5-8. The school is located in a neighborhood that has deep historical and cultural connections among residents, with a history of arts and activist cultures. Currently, the area hosts multiple business incubators as well as a health clinic, a daycare service, and most recently, Smithtown Public Charter School.

Unlike other charter schools with larger network ties, Smithtown Charter arose out of the desire from parents to have a high-quality neighborhood school option that also allows for social and emotional growth. The non-profit umbrella, Smithtown Inc, is the manager of the charter for the school. Shortly after the school was founded in 2015, the principal of the school resigned. The school principal position was then taken over by a board member who had local context for the Smithtown community. At the end of the year, a new principal was selected and brought in from Washington, DC, to lead the school. The result of the administrative changes in the early days of the school meant that there was nearly 100% staff turnover, including both administrative and teaching branches of the school.

While Middleton and Smithtown had a history of collaboration through initiatives led by the business department at the college, the education department had not enthusiastically partnered with the school in the past, largely due to their preexisting ties to schools in the public school district. However, after being invited personally to engage in more collaborations with the school, the Middleton professor (Author 1) reached out to the principal and then the after-school director (Author 2) to see if there would be any interest in a sustained semester-long collaboration. It became quickly apparent that the after school director shared great interest in expanding views of multimodal literacies as well as teacher mentorship/growth, and we quickly moved to coconstruct the field experience as a central component of the Literacy 2 experience.

Literacy Education Course

Literacy 2 serves as the second course in the literacy sequence for elementary education majors at Middleton, centrally focusing on preparing future teachers to work with upper elementary and middle school students. In addition, its design was largely informed by CL principles and culturally sustaining pedagogies, which are specifically situated in the course in the following sections.

CL Principles

Connections beyond the classroom. Literacy 2 was designed to be field-centric, and students spent about two thirds of the time dedicated to the course actively engaging with young people (a) leading guided reading groups at a nearby private school and (b) planning for and implementing after-school clubs for students at Smithtown Public Charter. In addition, both field experiences were actively coconstructed with K-12 partners rather than merely the college professor. Our collaboration with Smithtown featured Author 2 as an involved mentor for PSTs, and during the partnership we leveraged other community members as experts for the middle school students to glean from, such as when the podcast club video-conferenced (via Skype) with someone who made podcasts professionally or when a leader at the local National Public Radio station came and assisted groups with their interviewing skills.

Production-centered. The focal goal for both clubs involved production. PSTs worked with the fifth and sixth graders in their clubs to compose their own digital graphic novel (using Pixton, https://www.pixton.com/) or an original group podcast, which were showcased at a culminating event. Family and community members were invited to Middleton College to view and listen to their young scholars’ creations. During the course of the semester, PSTs utilized a variety of mentor texts, such as March, John Lewis’ graphic novel series about civil rights or a podcast episode on This American Life (2011) about Middle School (https://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/449/middle-school). Such texts enabled students to deconstruct the genres and the compositional modes available in graphic novels and podcasts.

Utilization of new media for connected purposes. Literacy 2 takes a broader view on defining literacy as “meaning-making” and pays special attention to opening up opportunities for students to make meaning using a range of tools, including multiple modes such as sound, image, and movement. Throughout the Literacy Course, PSTs were called upon to utilize a range of platforms and tools in order to collaborate on lesson plans and to reflect on difficulties and successes encountered during the facilitation of clubs. In addition, as their final for the course, the graphic novel club leaders were asked to create their own graphic novel reflection about the semester (see Appendix A) and the podcast club leaders were asked to create their own podcast reflection (Audio 1). [Editor’s Note: URLs for audio files are listed in the Resources section at the end of this paper.] Table 1 provides a list of the digital tools and platforms that enabled many of the connected learning/teaching experiences throughout the semester.

Interest driven. Youth at Smithtown chose whether or not they enrolled in either podcast or graphic novels club. In addition, they had autonomy in choosing the subject, theme, and content of their graphic novel and podcast.

Shared purpose/peer support. PSTs facilitated clubs in groups of either two or three in order to build supportive networks in their shared purpose of creating meaningful experiences for youth. In addition, they promoted the shared purpose of the final community share-out event to the students in the club to motivate their participation in production.

Orientation toward socio-political justice. As initially described, students were engaged in two different field contexts. These two divergent contexts (an independent school largely serving young people from high socio-economic contexts and a public charter school largely serving young people from lower socio-economic contexts) were chosen intentionally by the professor of the course (first author) in order to highlight important discussions around equity and access.

Table 1

Connecting Platforms and Data Sources

Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy

The focal field experience for this article involves the design and facilitation of either a graphic novel club or a podcast club for 2 hours every Wednesday for students enrolled in the after-school program at Smithtown Public Charter. This kind of open-ended, expression-driven activity for youth engaged our PSTs directly in an “asset pedagogy” approach that remains starkly at odds with deficit or even just difference approaches (Paris & Alim, 2014). As PSTs encouraged the middle school students to shape their own personal graphic novels or choose a topic for their podcast, they worked actively to “support young people in sustaining the cultural and linguistic competence of their communities while simultaneously offering access to dominant cultural competence” (as in Paris, 2012, p. 95).

While the course was initially designed with CSP in mind, it was also a resonant theme that we had to revisit continually throughout implementation of the course. For instance, as will be described in depth in the findings, at one point we found that the narratives PSTs were producing about their young, black students were at odds with a CSP lens, and worked to facilitate a consciousness-raising intervention among our white PSTs. The course implementation also highlighted the fact that CRP and CSP are not unidirectional methods to be used by teachers on students but, rather, an interactive process in which teacher identity and reflexivity plays a critical role.

Data Sources

Table 1 lists nearly all of the data sources that were drawn upon for this particular study. Focal artifacts used in this article consist of transcriptions of PSTs’ weekly VoiceThread reflective video posts, the podcast and digital graphic novel completed by each group of PSTs near the end of the semester, final individual written reflections turned in at the end of the course, and follow-up interviews the semester after the course had finished. Figure 1 is a screenshot of the Literacy 2 VoiceThread homepage.

VoiceThread posts contributed the largest corpus of data. All five PSTs contributed one post each week of the semester and were also required to comment on at least two of their colleagues’ posts per week. As you can see in Figure 1, PSTs generally used the most informal VoiceThread capacity: speaking into their laptop’s webcam to record their observations of the week. The floating heads on the left of each post (see Figure 2) feature comments that PSTs left for each other, which most often functioned as affirmation and encouragement but also served a collaborative problem-solving function as well. PSTs could choose to comment using text, video, or audio but most commonly chose to type in text for comments. VoiceThreads as data sources provided unique insight into the on-the-ground, affect-laden experiences from Week 1- Week 13 of the course. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the semester was experienced as an emotional roller coaster for PSTs; one week could be phenomenal and the next could drive the teacher candidate to tears of frustration.

Appendix B links to the assignment sheet, which asked PSTs to complete their final project for the course: a collaboratively created podcast or graphic novel summing up what they learned from the facilitation of the after-school club (shared with the group on the last day of class) and an individual written reflection submitted just to the professor of the course. These pieces served to portray a macroview of the semester, and it was clear that PSTs felt the urge to package their club experiences in traditional narrative form, complete with a happy ending.

Finally, first author Rust conducted semistructured interviews in fall 2017 (the semester after the completion of the project) with all five PST participants to ask some more-focused questions related to the emerging findings and engage in member check. In addition, we were interested in determining if the space of time had shifted the way that PSTs made sense of the experience. (See Appendix C for interview protocol.)

Focal Participants

Table 2 features all five undergraduate participants (all of whom were second semester juniors) who were enrolled in Literacy 2. Note that, while all participants self-identified as white-cis-female-middle-class, they varied a great deal in their future teaching goals as well as in their previous K-12 schooling experiences. We include the information in Table 2 because it may illuminate why PSTs experienced the semester in divergent ways.

Table 2

Participant Chart

| Participant & Club | Demographics | K-12 Schooling | Future Professional Goals | Other Notes of Interest | Audio Clips |

| Jennifer GRAPHIC NOVEL | 21 White Female Middle Class | Private Christian School in Montgomery, AL | Teach lower elementary at private school; Occupational Therapy | *Less interested in working with this age group and context | Audio 7 Audio 9 Audio 11 Audio 20 |

| Megan GRAPHIC NOVEL | 22 White Female Middle Class | Suburban Public school, class size of 364 | “Advocate for secondary school music programs for student innovation, NOT for increased test scores” | *Leader in graphic novels group *Worked all year as an after-school tutor at Smithtown Charter so already had established relationship with scholars | Audio 6 Audio 14 Audio 17 Audio 21 |

| Patricia PODCAST | 21 White Female Middle Class | PK-7 (private); 8-12th (public) in Baton Rouge, LA | Teach Middle School Earth Science | *Had previous experience with writing workshop practices in creative writing course | Audio 5 Audio 18 |

| Sam PODCAST | 21 White Female Middle Class | *Suburban public schools *Public residential arts magnet school | “Influence students of various ages to allow ‘musician’ to enter into their identity. first with younger students, then with college students” | *Initially engaged in data analysis as part of the research team | Audio 8 Audio 13 Audio 16 |

| Kenna PODCAST | 20 White Female Middle Class | Rural Public School in Randolph, MS | Elementary, rural school from home | *First semester at Middleton (Transfer Student) | Audio 10 Audio 12 Audio 19 |

Analytical Methods

Rather than engage in rigid qualitative coding practice, we (and at the beginning of the study, one of the undergraduate PSTs enrolled in the course) met regularly as a team of both research collaborators and participants in the project to look at the myriad of collected artifacts (VoiceThread reflections, final podcast/graphic novel, and individual reflections), recount our semester together, and pay special attention to “felt focal moments” in which we experienced affective intensities (Hollett & Ehret, 2015). After noting the proliferation of moments of tension and negotiation in PST reflections, we leveraged “thinking with theory” (Jackson & Mazzei, 2012), an approach which pushes researchers to move away from patterns into “the mangle of the micro” its multifaceted, contextually situated variables.

Thinking with theory pushed us to mark moments of what we initially called moments of “tension” or “disruption” before settling on Deluezze and Guattari’s (1987) theoretical framing of deterritorialization. It seems apropos that we began mining for moments of PST deterritorialization even as we hoped to, as researchers, avoid getting mired in more territorialized, well-worn codes and methodological practices.

We then began to leave tracks of our thinking on shared color-coded Google docs, which we interrogated together as a group at our next meeting. One example of such thinking can be found in Appendix D. Once the semester began, our undergraduate collaborator (referred to in this manuscript as Sam) bowed out of collaborating on the publication due to other time demands, but her early contributions in our regular meetings were vital in unpacking the complicated experience of PSTs throughout the semester. As we looked through our corpus of data, we began to notice trends of deterritorialization practices. Throughout the semester, PSTs largely seemed to articulate lines of flight about themselves as teachers and about the middle school students they were working with, the dual subjects of our finding section that follows.

Findings

As PSTs moved through a semester that was collaborative, production-centered, interest-driven, and equity-focused (all tenants of CL), they encountered a barrage of questions and challenges that they previously had not encountered in more traditional (and less involved) field experiences. These challenges resulted in frustration and renegotiation, and rarely did they resolve into a neat and tidy best practice realization. Relationships (between PSTs, between PSTs and the professor and after-school director, between PSTs and the middle schoolers they worked with) were central to both initiating and making sense of the deterritorializing lines of flight that resulted.

The connected learning/teaching elements in the course enabled teacher candidates in the course to deterritorialize (a) conceptions of self as teacher and (b) conceptions of “the other” (the middle school students with whom they worked). Of course, these two buckets of deterritorialization practices do not, in reality, exist as distinct and separate. The single PST utterance of, “I felt terribly about how noisy clubs were when we discussed the podcast,” contains a symphony of players including (but not limited to) self, other, and what counts as literacy instruction.

Throughout this section, multimodal resources are presented to contextualize and deepen understandings of our teacher education approach and results in this article, including a link to the PSTs final podcasts, the digital version of the final graphic novel, and audio snippets of PST video reflections. (Note that all artifacts include pseudonyms to protect the identities of our participants, so we edited the audio and graphic novel when necessary to blind participant and school names.)

This immersive experience, particularly hearing the vocal inflections of PSTs working through the semester, helps readers of this piece understand the complex and rich journey this course inspired in a way that purely written text does not. This publication may also be a useful resource for PSTs, professors, and school administrators, thus we provide as much detail as possible to allow for understanding and replication.

Deterritorializing Self

During this intensely applied experience, teacher candidates consistently referenced their own evolving sense of self as teacher. At the end of the semester, Sam had the following to say in her group’s reflective podcast about working with Smithtown students:

Smithtown kids taught me that you bring your entire self into the room…. You bring your culture, you bring your religious upbringing, you bring your sibling problems, you bring your concerns that your friends are laughing at you, you bring your academic aptitude, you bring the style of classroom you are used to whether it be regimented or free and autonomous, you bring your interests, you bring your previous knowledge and thousands of other things that we couldn’t even name. (Audio 2)

This recognition of the impact of personal experiences and identities, past-present-future, upon teacher classroom practice itself was in itself a deterritorialization of sorts, one that destabilized the assumed amount of control they felt they had in performing a particular self. In fact, earlier in the semester Sam had a breakthrough moment with another peer leading her podcast group: “I struggle with being able to tell where people are coming from because school has always been easy for me.” Seeing the interplay between her identity as student and her evolving identity as teacher helped Sam deterritorialize some assumptions about self and other. In this section, we more deeply probe the moments in which PSTs’ work with after-school literacy clubs unsettled assumed narratives of self as evolving teacher.

From time to time, the lines of flight of self that PSTs experienced during the course felt liberating. Megan, for instance, described the way her participation in the graphic novel club (and her creation of her final graphic novel project) was deterritorializing, as it shifted her own view of herself to include writerly identities:

The positive of making a graphic novel myself was experiencing the same thing my scholars did – my identity as a writer. I have always been very comfortable in my personality and my humor, but I never really let it show in my writing before.

Megan’s movement toward a writerly identity signaled the kind of trajectory that empowered her to be a classroom leader who triggers the same kinds of reader/writer affiliations and identity practices for her future students (as suggested also by Cremin & Baker, 2014). Such a stance positioned Megan to write with her students, to invite young people into the community of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991) of those who compose and revise and share for authentic audiences.

Kenna and Patricia described experiencing a different (but still powerful) sense of liberation when their experience leading podcast club deterritorialized their figured world of the teacher self as being perfect and expert. Kenna explained this carefully in her role in the group’s final podcast

Smithtown kids taught me to give myself a break…. I was above average to them…. I was everything they wanted me to be […reading quote…] You’re not superwoman, and no one has to be. (Audio 3)

The realization that teachers don’t have to be superheroes invoke one of the most vital realities of becoming a teacher, what Deborah Britzman (2003) called “the more private aspects of pedagogy: coping with competing definitions of success and failure, and one’s own sense of vulnerability and credibility” (p. 28).

Kenna was not the only PST who experienced this reality check. In the final podcast, her words were followed by a sentence spoken in chorus by all three PST facilitators of the podcast club: “Smithtown kids taught us to accept the reality of not knowing.” In her final written reflection, Patricia articulated the following:

How do you handle a question from your students that you cannot answer? How do you answer that? … You as the educator humbly look your students in the eye and say, “You know what? I have no idea what the answer to your question is, but I bet together we can figure it out…. Once I decided that it is okay to not have all the answers, I found a whole new world for myself and my students. This view is me as the educator being okay with not being the smartest person in the room.

Her line of flight from teacher self as “smart” and “expert” to “it is okay to not have all the answers” resulted in her discovery of “a new world.” Because none of the members of podcast team had ever listened to a podcast before the start of this semester, this was a theme widely explored in her group’s final podcast. (For excerpts on this theme, listen to Audio 4.) Instead of positioning themselves as the source of knowledge, preservice teachers found themselves learning alongside their students.

Although at times deterritorializations of self were experienced as freeing, often they involved a painful process steeped in frustration and instability. Without a doubt, the most common complaint that emerged from PSTs in the applied experience arose around the difficulties in establishing a positive, productive learning environment. This finding is unsurprising, as classroom management is also one of the most common themes of becoming a teacher and remains one of the most urgent challenges new teachers face (Dicke, Elling, Schmeck, & Leutner, 2015).

Upon closer inspection, however, PST reflections about difficulties with students often centered more on the self future teachers wanted to project as authority figures in a space. Patricia articulated this self-other connection clearly when she described having a “let’s get real” chat with her club:

[Smithtown] was … wild until … me and Kenna were like “You know, you guys’ behavior is a reflection of me and Miss Kenna and Miss Sam…. We get a grade for this, and I’m done putting up with this, so three strikes is done. If you don’t want to be here, I’m not doing it…. We only have three classes left.” They shaped up and [our professor] made a great point…. I’m thinking they shaped up because they liked us and they do care about us. (Audio 5)

Seeing the middle schooler’s behavior as a direct reflection of their evolving status as teacher set the stage for an emotional roller coaster for the PSTs, who continually evaluated their success each week as directly correlated their ability to engage and positively direct the Smithtown young people. However, the ways in which the PSTs read the negotiation between self (as teacher) and other (as student) shifted as the semester went on. For instance, about midsemester, Kenna, who at the beginning of the semester had been thrilled when one middle schooler mistook her for a student in the class, noted that “we’re their friends, but they also need to understand we are also their superiors.”

Megan, who knew the scholars before the experience due to her work at Smithtown with the after-school program, continually expressed frustration at her desire for the experience to be fun but the need for her to act tough. She described her “trying on” a range of teacher identities, to no avail:

I don’t know the solution. I’ve tried the nurturing teacher and now I end up being a counselor all day, and now they just walk up to me and say, “Can I just talk to you in private?”… “No you cannot; I have class!” And I try the really strict no-nonsense approach, which, like, they get all the time, and it doesn’t take a difference, like whatever…. I even try to find a happy medium where they are like confused, like, “Are you being nice or are you being mean?” … and literally it’s crazy and I’m so lost and … I don’t know, maybe it’s just because I’m a young female and they know I’m a college student, and it’s like, “no power here.” (Audio 6)

Megan tried on a range of identities: from nurturing teacher to counselor to strict to happy medium. Her experimentation was not birthed out of delight or play, but out of a sense of powerlessness, frustration, of “nothing working.” This range was also experienced by Jennifer, her graphic novels club partner, who described a similar tinkering of approaches that resulted in different portrayals of self as teacher with one student, in particular:

I’ve tried having a meaningful conversation with; I’ve tried talking to him straight; I’ve tried (I hate to say this) yelling, being firm with him, and he just doesn’t listen. It’s the most frustrating thing ever, and I just can’t. At one point I literally just was like, “Know what? I’m done. I just can’t do anything.” So I walked away. And I hate doing that, because I want to reach him so bad, but no matter what I do no matter what I say he just doesn’t listen. He’s not gonna respect me. (Audio 7)

Nearly all of these uncomfortable reexaminations of the self that was previously assumed to be stable involved an interplay between conceptions of self (as teacher/authority) and the other (Smithtown scholars/reality). The two overlapping figured worlds always entered the stage together, at times dancing choreographed in sync and other times awkwardly stomping on each other’s toes. In the next section, we describe our examination of the ways that PSTs found their assumptions about the other disrupted throughout this connected learning/teaching experience.

Other

Throughout the ups and downs of the semester, our conceptions of others were routinely decentered. However, the most vivid deterritorialization of other emerged when PSTs discussed the Smithtown scholars with various turns of surprise, transformation, and an increasing recognition of their complexity as humans. This evolving perception of Smithtown scholars is the subject of this section.

It is first important to understand that the general narrative across the semester that PSTs continuously reiterated was the narrative of Smithtown kids as being incredibly difficult to “manage.” Yoon (2016) highlighted the power that such storytelling among white female teachers in framing particular students and their communities:

Stories reveal contradictions as they transmit and construct shared knowledge. How teachers learn to recognize and politicize their social locations and organizational contexts may be the difference between stories that are told to reassert social distance and moral superiority to benefit the teller, and stories that are used to challenge racial, social class, and gender oppression in schools. Challenging these everyday discourses has significance for teachers’ identities, students’ experiences, and the larger goal of equitable education. (p. 38-39)

Stories that circulated among preservice teachers about these young, black youth located in a lower socioeconomic neighborhood that foregrounded their misbehavior in classroom spaces, then, had the potential to do damage, reifying already existing assumptions about their communities. Instead, across the PST reflection data, there were allusions to several forces that triggered a new way of seeing the Smithtown others that paved the way for challenging narratives focused on student deficits.

Midway through the semester, for instance, the graphic novels club decided to switch meeting rooms from a cramped room with one table to a large lecture-style hall. Megan reported, “The big room helped a lot, because kids like space, right? That is more beneficial, and we got a lot more done and management issues were almost a complete zero.” Similarly, Patricia noted a distinct shift in how she viewed her club when they shifted to work on podcasts in three small separate groups (one PST per group) rather than one large group: “They do so much better in small groups, that teacher one on oneness…they don’t have each other to feed off of, and it was just a really good week.”

Access to technology similarly deterritorialized PSTs’ sense of who the Smithtown children were. In perhaps her most optimistic post about the club experience, Jennifer discussed the transformational power of getting laptops out to work on digital graphic novels

The best week at Smithtown. My word, they were amazing. They were so focused on their laptops and actually doing what they were supposed to be doing and it was really cool…. Because the past few weeks, it was really rough. It was really cool to see them actually engaged and excited about doing their graphic novels. (Audio 9)

Another deterritorializing force in PSTs’ vision of the Smithtown scholars manifested the day that podcast club video conferenced in a friend of second author Cantwell, who happened to do podcasts professionally. Finding mentors outside the school walls is a key principle in connected learning. Kenna specifically described one middle schooler named Ron in this way.

I want to specifically talk about Ron. He’s not really a problem child; he just doesn’t want to do what we’re doing. I asked who wanted to throw the pitch, and he volunteered. We were just discussing a bunch of questions, and he was writing every single thing down, and whenever we had the conference call with Katherine, he couldn’t stop asking questions. It was so great because he was so into it. After they left, [Cantwell] said in [a text message] that Ron was telling them all about it, like he was so pumped about it, so I think that was really a key for getting kids to see that podcasting can be fun, because somebody does it for a living. (Audio 10)

Much of the time deterritorialization practices revolved around the sudden realization that Smithtown young people were incredibly smart and capable, as in this example. This element of shifting expectations was not surprising given the existing literature around racial gaps in how teachers perceive student performance. Irizarry’s (2015) study on teacher evaluations of student performance found that “minority students are less positively perceived than their white peers” (p.535). With the PST’s concurrent placement at a high-performing, primarily white school, this weekly juxtaposition possibly created unintentional reinforcements for the misconception that black students would be less capable of performing with academic brilliance.

Irizarry (2015) noted in her analysis that the mindset of teachers has a significant impact on the actual discourse of the classroom environment. Irizarry discussed that “having less positive perceptions of some high-performing minority students may also shape teachers’ expectations of and interaction with these students in ways that may limit them from performing to their full potential” (p. 535). The stories of Ron, as well as Karly and Faith in the following sections, highlight direct challenges to PST’s beliefs of Smithtown students and show the interruptions of those beliefs through counter narrative action.

Jennifer marveled at the fact that so many students had finished their novels: “Oh my word. That’s just crazy. I didn’t think you’d ever get here, but there we are.” (Audio 11)

Kenna similarly registered amazement when one previously disengaged student, a seventh grader stuck in a group with primarily fifth graders, rose to new heights as they discussed an engaging podcast about middle school.

Karly like, really got into it. Like, she wanted to tell them how middle school was, she wanted to tell them not to be afraid of stuff, and it was really great to have Karly just with us instead of just there. She was taking notes on the podcast; she actually felt like part of the club this time instead of just a body. And I do think that she feels higher up than anybody else, and she is. She’s super smart, and I feel like she’s bored most of the days. But this week was awesome. (Audio 12)

While PSTs recounted many paradigm shifts about specific students throughout the semester, two students in particular came up again and again: Faith in podcast club and Caleb in graphic novels club. Both proved to be challenging disciplinarily throughout the course of the semester, often distracting their young peers as they performed for social purposes rather than the more academic tasks at hand. Sam, however, found herself revising this narrative around Faith as she went deeper into the semester.

In Week 6, she reflected that Faith was “on point . . . stellar” and was contributing “very intuitive and thoughtful reflections” and then connecting these observations to their own podcast project. Sam went on to explain as follows:

…And it really raised the bar for me for these students, because once they buy in, they have got some really good things to say…. I think I’m going to say, “Wow, I’ve seen some really great things you’ve done, and ya’ll are going to have to step it up and do that every single darn time!” (Audio 13)

Significant in this case is the fact that the deterritorialization of Sam’s perception of Faith resulted in a more macro paradigm shift about what she could or could not expect out of the Smithtown kids. The power of teacher expectation on student learning and engagement has been widely studied (e.g., Jussim & Eccles, 1992), so this shift is no small accomplishment.

Caleb’s trajectory in graphic novels club moved from being a “significant management issue who got under the table and refused to participate,” getting kicked out of clubs due to repeated documented infractions, and then being allowed to join clubs again when he “snuck on the bus … and proved he could #chill.” (See Figure 3.)

On the final share out event, PSTs remarked on being stunned by Caleb’s transformation, but none were more moved than Megan.

The final event was just so amazing, and I have no idea if you know, but I definitely cried because when Caleb got behind his graphic novel and started to present it to his mom and stepdad, I was like “Uhhh,” cause he was just so proud…. It did my heart a lot of good to see that. … I don’t think there’s anything more satisfying than seeing how happy they were presenting their graphic novels…. It made me realize this is why I want to be a teacher. Because it’s been a really, really rough semester, as we all really know, and when you got to see everything come together and how proud they were and how awesome the environment was, it made everything worth it…. It was very gratifying, and I literally walked away from Caleb’s speech so I could dab my eyes. (Audio 14).

Interestingly, the deterritorialization of Caleb that Megan experienced simultaneously affirmed her commitment to the vocation of teacher.

While these deterritorializations of other all emerged organically out of the connected teaching/learning nature of the course, we found the need to design a more deliberate deterritorialization moment in the middle of the course during the 13th week of the semester. We had a conversation about the recurrent themes that were emerging from preservice teachers facilitating the clubs about Smithtown young people being incredibly difficult to manage, general disorganization at the school, and archetypes about Smithtown parents and community members.

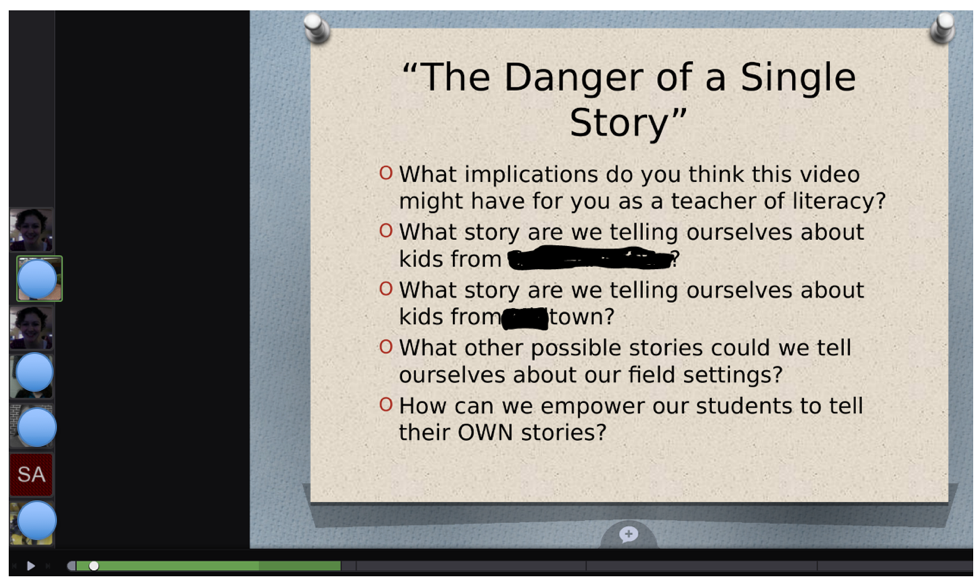

While there were good reasons that PSTs needed to express and work through real challenges that were not manufactured, we began to wonder if they might emerge from the semester with negative assumptions about the community of Smithtown. Cantwell suggested that Rust assign PSTs to view and reflect on Chimamanda Adichie’s The Danger of a Single Story (https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story), a powerful Ted Talk that emphasizes the importance of pushing beyond a single vision of what a group of persons might be. Figure 5 features the virtual class slide that students were asked to respond to after viewing the video.

In their Voicethread comments, several students reacted strongly. Megan explained,

When describing Smithtown to other people, I find myself in a trap of saying, “Poor little black kids with parents that don’t care,” even though I’ve seen other stories, but that first impression stuck with me. There’s a story of ignorance. There are things we just don’t know. And we can try to figure it out, hypothesize. We have no idea what each individual child’s story is. Unfortunately, we get a first impression and we stick with it. [It’s important to] take the time to get to know each child’s story.

An essential first step to (re)imagining other is articulating one’s initial preconceptions and then finding holes or gaps in those assumptions. Kenna similarly was brave in exposing her curvy trajectory in perception of other:

First week was perfect. But then Week 2 came, and they were, like, “We’re gonna be familiar with you,” but then the story changed. Took a 180 and flipped. I don’t have words for the story I had, but man. I tried to talk myself out of it. “These are just little brats too, these are ghetto brats because of where they are located,” and that’s completely bad, I shouldn’t say it, and that’s the story I had about [Smithtown]. Now I take a step back. We have to tell ourselves that things change. Everything isn’t what I think it is.

Patricia similarly expressed, “This opens my eyes tremendously to field settings and realizing I judged books by the cover and I didn’t even mean to. I didn’t mean to make up a story, but I did.” Jennifer found herself moving from a more deficit perspective of the Smithtown students to a funds-of-knowledge (Moll, Amanti, Neff & Gozalez, 1992) perspective.

Not just being like, “Oh they don’t have anything we have,” “They don’t have all this,” but really teaching, “They don’t have this, but they have THIS,” telling the stories that are important. One little snapshot of someone, that’s not a definition of who they are.

Sam’s realization that “these kids are just not in the textbook” and the “messy . . . intersectional” nature of engaging with young people for whom “social dynamics are more pressing . . more interesting” was a painful process, one that produced stress and frustration in the moment. The theme, however, proved to compel her throughout the remainder of the project and surfaced in the podcast team’s final podcast contribution multiple times.

I can’t tell you the many times [the lesson plan] said “brainstorm or discussion,” and it just diverted very quickly into “You like her,” or “I got two side chicks so I gotta make sure my girlfriend doesn’t get my phone.” But it’s easy for us to be, “Oh wow, they’re so stupid.” We get so frustrated, but that’s where they’re at in their development. They’ve got to figure out what it means to be in a healthy relationship versus a non-healthy relationship. They bring their entire self into the classroom; they can’t just leave that part out. (Audio 15)

For her part in the podcast, Sam took the time to look up and read an article on intersectionality, a theory she described as holding a lot of hope for her. She recited one quote that in many ways exemplifies the most central deterritorialization of stories of others – the recognition of them as nuanced people.

Everyday kids enter our class there’s an opportunity for them to be empowered or oppressed…. When I don’t consider intersectionality and what they might need, I run the risk of oppressing my kids…. When we stop seeing our kids as whole people, as whole nuanced people with context to race and gender, and class, we stop seeing them as real people. (Bell, 2016) (Audio 16)

Implications

The spring 2017 iteration of Literacy 2 demanded much more out of all of us than a traditional education course might have: the professor who mediated the curricular objectives of the literacy sequence with the rich reality of practical application; the after-school director who actively read and provided feedback for lesson plans each week, engaged active observations of PSTs teaching, and helped transport students back and forth to campus each week; and the PSTs enrolled in the course, who jumped willingly into designing and implementing club sessions for middle schoolers they had not met revolving around genres (podcasts and graphic novels) they had little previous exposure to.

Simply redesigning a teacher education course to embed CL practices does not ensure smooth sailing; in fact, we observed the opposite. In an anonymous midterm evaluation comment, one PST called for the program to be shut down because of difficulties in establishing a positive learning environment. From week to week, PSTs had radically different feelings on the course and particularly the Smithtown partnership. This intensity, however, paved the way for the number of deterritorializations we found. Connected learning/teaching experiences in teacher education in some ways push the fast-forward button in teacher development, pushing future teachers into more pivotal experiences that better resemble the first year of teaching, except with more support and time to work through challenges. We end this piece with a series of lessons learned that might make the way more clear for those that are interested in cultivating similarly powerful connected learning/teaching moments for teacher candidates in “all manners of becoming” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987, p. 21)

The Role of the Teacher Educator

CL spaces automatically shift the role of the teacher from front and center to coach on the side. Although this was not a radical shift from most of Author Rust’s traditional positioning as professor, she did experience a sense of disequilibrium at the vast amount of course content that the PSTs had to forego to make space and time for clubs. Often, the needs of the club facilitators were so pressing that they would even consume the once-weekly face-to-face class meetings reserved to discuss the other topics of the course. Teacher educators considering such an experience should be prepared to address the question of “what must be given up” to make space for the connected partnership to flourish.

When and how moments of disruption should either take their natural course or be deliberately designed into the curricula is another key question. For example, asking students to watch the Ted Talk about stereotypes was a designed intervention meant to disrupt some PST understandings, while PSTs’ evolving appreciation of students initially perceived as troublemakers (e.g., Caleb and Faith) emerged organically, as a result of building relationships and engaging in a collaborative project. Preservice teachers may learn more from moments that happen naturally in CL spaces, but well-timed deliberate deterritorializing forces may also prompt change. Our analysis suggests that both can be incredibly powerful for PSTs, particularly when accompanied with supportive reflective spaces.

Fostering Positive Peer Support

As one of the key tenets of CL, fostering spaces in which PSTs are peer supported during challenging authentic teaching and learning is key. In fact, “the most resilient, adaptive, and effective learning involves individual interest as well as social support to overcome adversity and provide recognition.” (Ito et al., 2012, p. 4) In some ways, this support came easily in our context. Middleton College is a tiny school in which courses, especially more advanced courses in their major, are typically between 5-10 students in size. Having such a small cohort of fellow-majors can be a dream (or a nightmare), depending on the composition of your group, and in this case, we were lucky to have a highly collaborative group of college juniors.

The key platform that we used for communal support throughout experience was VoiceThread. Sam reflected on the purpose of the platform in her post interview the semester after the course ended:

Honestly, like whining about [clubs] in class and on VoiceThread was so productive…. It was a good just workshopping space of like “this thing happened and I don’t know what the f#$% to do … about it.” [laughs]…. That social aspect of the class made us. It was like we were in a war together…. And we were all on this team, and we got so close because we were like, “What do we do with this student? We want to help him so bad.”

Sam’s quotation about being on the same “team…like we were in a war together” points to the shared purpose commitment in CL. While the VoiceThread posts were mediated by not only peers but also the professor of the course, however, there were many other backchannel methods of communication between team members. In a postinterview one PST revealed that she and another peer texted each other complaints about the club facilitation experience throughout the semester, which she experienced as a fostering negative attitudes, “feeding off of each other” about the club experience and the Smithtown scholars.

It is fascinating that Sam described the peer “whining” on VoiceThread as “productive,” while Megan experienced backchannel “venting” texting as breeding negative attitudes. Just putting peers together to support each other in shared purpose, then, does not necessarily result in positive synergy. PSTs can come together to strengthen, embolden, and support each other’s pursuits, but they can also fuel each other in negative ways that are draining and emphasize the deficits of community partners. Being aware of both possibilities is important in designing participatory reflective spaces (which are often mediated by technology) for PSTs to make sense of intensely connected teaching/learning experiences.

Final Remarks

These connected learning and teaching experiences paved the way for students to interrogate deeply their previously existing assumptions around “who they would be” as teacher and what to expect from the richly intersectional lives of black youth who reside in communities like Smithtown. The development of teacher identities and the leveraging of CL in digital literacy are inextricably linked. Teacher education is viscerally enlivened when it is coconstructed with authentic, intense teaching and learning K-12 experiences at the center. However, such courses must also be designed to encompass practices of critical reflection that inspire future teachers to take a second look at their evolving teaching selves as well as their perceptions of the students and communities they serve.

Teacher education programs and courses that serve PSTs should engage with issues of race, class, and privilege as core components of instructional preparation. However, providing teachers with frameworks, theory, and best practices is not merely enough. PSTs must see themselves as a critical tool in the process of teaching and learning and must constantly be interrogating their own always-evolving, always-incomplete perceptions of self and other.

Author Note

Special thanks to Sarah Altman, a preservice teacher participant in this study who also invested a good amount of time in meeting with us to plan and think through the early stages of this manuscript. Although other commitments pulled her away from joining us as third author for this piece, her imprint is most certainly apparent, and this piece is better-informed because of her insider perspective.

References

Allan, J. (2004). Deterritorializations: Putting postmodernism to work on teacher education and inclusion. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 36(4), 417-432.

Baker-Doyle, K. (2017). #CLinTE in the making: Co-designing the connected learning in teacher ed gathering. Retrieved from https://kbakerdoyle.wordpress.com/2017/07/13/clinte-in-the-making-co-designing-the-connected-learning-in-teacher-ed-gathering/

Ball, D., & Cohen, D. (1999). Developing practice, developing practitioners: Toward a practice-based theory of professional education. In L. Darling-Hammond & G. Sykes (Eds.), Teaching as a learning profession (pp. 3-32). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bell, M. (2016). Teaching at the Intersections. Edutopia. Retrieved from https://www.tolerance.org/magazine/summer-2016/teaching-at-the-intersections

Bloom, D., Peters, T., Margolin, M., & Fragnoli, F. (2013). Are my students like me?: The path to color-blindness and white racial identity development. Education and Urban Society, 47(5), 555–575. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124513499929

Britzman, D. P. (2003). Practice makes practice: A critical study of learning to teach. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Clark, P., Zygmunt, E., Clausen, J., Mucherah, W., & Tancock, S. (2015). Transforming teacher education for social justice. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Cremin, T., & Baker, S. (2014). Exploring the discursively constructed identities of a teacher-writer teaching writing. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 13(3), 30-55.

Damico, J., & Rust, J. (2010). Dwelling in the spaces between “what is” and “what could be”: The view from a university-based content literacy course at semester’s end. Journal of Language and Literacy Education, 6(2), 103-110.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Constructing 21st-century teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 57(3), 300-314.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Delpit, L. (1988). The silenced dialogue: Power and pedagogy in educating other people’s children. Harvard Educational Review, 58(3), 280-299.

Dicke, T., Elling, J., Schmeck, A., & Leutner, D. (2015). Reducing reality shock: The effects of classroom management skills training on beginning teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 48, 1-12.

Garcia, A. (Ed.). (2014). Teaching in the connected learning classroom. Irvine, CA: Digital Media and Learning Research Hub. Retrieved from http://www.kyliepeppler.com/Docs/2014_Peppler_Teaching-in-the-CL-classroom.pdf

Gelfuso, A., Parker, A., & Dennis, D. V. (2015). Turning teacher education upside down: Enacting the inversion of teacher preparation through the symbiotic relationship of theory and practice. The Professional Educator, 39(2), 1.

Hollett, T., & Ehret, C. (2015). Bean’s world: (Mine)crafting affective atmospheres for game-play, learning and care in a children’s hospital. New Media & Society, 17, 1849-1866.

Horn, I. S., & Campbell, S. S. (2015). Developing pedagogical judgment in novice teachers: Mediated field experience as a pedagogy for teacher education. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 10(2), 149-176.

Irizarry, Y. (2015). Selling students short: Racial differences in teachers’ evaluations of high, average, and low performing students. Social Science Research, 52, 522–538. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.04.002

Ito, M., Gutiérrez, K., Livingstone, S., Penuel, B., Rhodes, J., Salen, K., … Watkins, C. (2013). Connected learning: An agenda for research and design. Irvine, Ca: Digital Media and Learning Research Hub. Retrieved from https://www.nwp.org/cs/public/download/nwp_file/17070/ConnectedLearning_report.pdf?x-r=pcfile_d

Jackson, A. Y., & Mazzei, L. A. (2012). Thinking with theory in qualitative research: Viewing data across multiple perspectives. London, UK: Routledge.

Jussim, L., & Eccles, J. S. (1992). Teacher expectations: II. Construction and reflection of student achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(6), 947.

Kuby, C. R., & Rucker, T. G. (2016). Go be a writer!: Expanding the curricular boundaries of literacy learning with children. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465-491.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Margaryan, A., Littlejohn, A., & Vojt, G. (2011). Are digital natives a myth or reality? University students’ use of digital technologies. Computers & education, 56(2), 429-440.

Mirra, N. (2017). From connected learning to connected teaching: A necessary step forward. Retrieved from http://educatorinnovator.org/from-connected-learning-to-connected-teaching-a-necessary-step-forward/

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017.

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into Practice, 31(2), 132-141.

Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational Researcher, 41(3), 93-97.

Paris, D., & Alim, H. S. (2014). What are we seeking to sustain through culturally sustaining pedagogy? A loving critique forward. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 85-100.

Pratt, M. L. (1991). Arts of the contact zone. Profession, 33-40.

Purcell, K., Buchanan, J., & Friedrich, L. (2013). The impact of digital tools on student writing and how writing is taught in schools. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Sanderson, D. R. (2016). Working together to strengthen the school community: The restructuring of a university-school partnership. School Community Journal, 26(1), 183.

Soti, N. Connected Learning in Practice. [Figure illustrated connected learning.] Reprinted from Connected Learning Alliance. Retrieved from https://clalliance.org/why-connected-learning/

Sumara, D. J., & Luce-Kapler, R. (1996). (Un)becoming a teacher: Negotiating identities while learning to teach. Canadian Journal of Education/Revue canadienne de l’éducation, 65-83.

This American Life. (2011, October 11). Middle school [Audio podcast]. Retrieved from https://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/449/middle-school

Waddell, J., & Vartuli, S. (2015). Moving from traditional teacher education to a field-based urban teacher education program: One program’s story of reform. The Professional Educator, 39(2), 1.

Yoon, I.H. (2016). Trading stories: Middle-class White women teachers and the creation of narratives about students and families in a diverse elementary school. Teachers College Record, 118(2).

Zeichner, K. (2012). The turn once again toward practice-based teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 63(5), 376-382.

Zeichner, K., Payne, K. A., & Brayko, K. (2015). Democratizing teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 66(2), 122-135.

Zygmunt, E., & Clark, P. (2016). Transforming teacher education for social justice. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Resources

Audio 1 – https://drive.google.com/file/d/1GoHsDsU3ERnPdXV5LtgAjgptUx58UCiP/view?usp=sharing

Audio 2 – https://drive.google.com/open?id=1NIrs1j-yqGHqfA0kFXwGdXpPRZaBoKQQ

Audio 3 – https://drive.google.com/open?id=1fyr0KoRuu1N-6tU_qCjolIZm3qqtM6lZ

Audio 4 – https://drive.google.com/open?id=1IXOJdUao-viK0iXLHh3VysX65MlxuFAS

Audio 5 – https://drive.google.com/open?id=1Dj9DmQit7NoQQRSQffHYScfD5fn7PiZR

Audio 6 – https://drive.google.com/file/d/1DC0ZIXQyOsQikBw5OUN7NNAma5zxRdw_/view?usp=sharing

Audio 7 – https://drive.google.com/open?id=1FE8o8MAd6Z1kjohhyGkNbC_LAmCUJqJj

Audio 9 – https://drive.google.com/open?id=1yqNlEZbq_HGm_hvKCUOmyDsHLIBl9H46

Audio 10 – https://drive.google.com/open?id=1r3Pj6dd5AdacBXxxZ6XIBiNHuS-rDu_N

Audio 11 – https://drive.google.com/open?id=17eRHn98PmllSj45XtKCKlN-cu8dQhxVl

Audio 12 – https://drive.google.com/file/d/18CGGYisvR3498fgS6aZMPjQmSsSrwpeJ/view?usp=sharing

Audio 13 – https://drive.google.com/open?id=1TMmcbYfr_NX21pXlBE0bTzW_pc9UqzoR

Audio 14 – https://drive.google.com/open?id=1U-1_h6dn4duNYhqXojR55tm6-4p32Cw9

Audio 15 – https://drive.google.com/file/d/1FyXa-NCtNcv0Qh4HRq7b1jCXf_rCLJN0/view?usp=sharing

Audio 16 – https://drive.google.com/open?id=18–sVOA9mE7rwYpHbPwj-VAsXX04p-bo

Appendix A

Final PST Graphic Novel Reflection

Appendix B

Assignment Sheet

FINAL PODCAST/GRAPHIC NOVEL (30 points; due Monday 4/24)

You’ve been working hard to make sense of podcasting/graphic novels for your Smithtown Clubs. Now it’s your turn. In this culminating assignment, you can choose to either work alone or with your club team to create a podcast or graphic novel. Your final project SHOULD include:

- 20 points: A podcast or graphic novel that shares a theme that relates to topics discussed in Literacy 2 OR that revolves around your experiences working on the field with students for Literacy 2.

- 5 points: A rubric that you construct to assess what a quality “podcast” or “graphic novel” might contain. I will use this to grade your project. (It should add up to 20 points.)

- 5 points: An individual 1 page reflection (each person in the team submits their own; will remain confidential) in which you address:

- What did you learn about teaching this form (podcast or graphic novel) by going through the process of creating your own? What was difficult? What was easy? If you were to begin Smithtown Clubs again next semester, how would you approach the project development differently knowing what you know now?

- Please list each of your team members’ names (including your own!) in your group and share details about what they contributed and/or failed to contribute in the final project and throughout the lesson planning/teaching days of the semester. This information will be kept confidential!

Appendix C

Post-Interview Protocol

BACKGROUND CONTEXT

- Can you tell me a little bit about your experience in schooling growing up? Where did you attend school? What kind of schools did you attend?

ON LITERACY 2

- What were you most excited about?

- What were you most nervous about?-

- What was the biggest struggle that you had during this course?

- How did you persevere through that struggle? What resources or people were helpful?

- What was the biggest success that you had during this course?

- What resources or people were helpful in making that successful?

- Question about collab lesson planning, revising, and feedback?

- We watched Chimamanda Adichie’s Danger of a Single Story about midway through the semester. Can you tell me about your thoughts on the video? Have you thought about it since?! In what ways . . .

- Principal question

- Podcast Specific: Tell the story of Faith . . .

- Graphic Novels Specific: Tell the story of Caleb . . .

BEFORE AND AFTER

- What did you learn in Literacy 1? How was that similar/different to what you learned in literacy 2?

- How would you describe your teaching philosophy before/after this course?

- How would you describe your classroom management before/after this course? How does it compare to what you observed in your colleagues leading the group?

- Tell me about your goals in education and teaching after this course.

- What was your perception of students from [private school] after the course?

- What was your perception of students from Smithtown after the course?

MEMBER CHECK

Deterritorialization:

- Self

- Others

- What counts as literacy

*Are there different focal events/shifting moments that come to mind in these three categories or in a different category?

Appendix D

Thinking With Theory

(pdf download for larger image)

![]()