“I never expected them to know so much! I can’t believe how much I’ve learned from [them].”

(Preservice teacher)

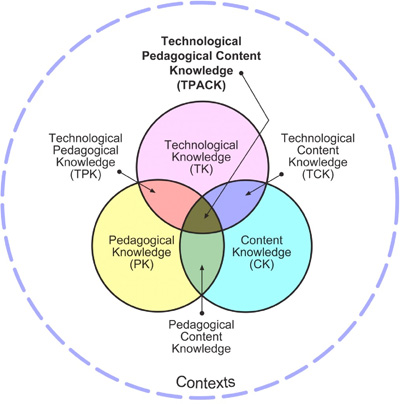

Much has been made in recent years of the technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK; now most frequently referenced as TPACK) framework (Mishra & Koehler, 2006; see Figure 1 for a visual representation of the TPACK framework.) Both research and practice have been informed by the literature and discussions that have emanated from TPACK’s emergence (Spires, Wiebe, Young, Hollebrand, & Lee, 2009), and books (The AACTE Committee on Innovation and Technology, 2008) and journal articles (Bull & Bell, 2009) have been based on its implications.

Figure 1. Illustration of TPACK framework. (Rights-free image from Matthew Koehler’s website: http://tpack.org)

Figure 1. Illustration of TPACK framework. (Rights-free image from Matthew Koehler’s website: http://tpack.org)

Why has TPACK so quickly and thoroughly captured the attention of teacher educators’ research and practice? Perhaps the reason for the positive response lies in the fact that the profession has long embraced the importance of content knowledge for the development of teachers, and pedagogical knowledge has long formed a bedrock for teacher education literature. When Shulman (1987) and Grossman (1990) introduced the concept of pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), the teacher education field welcomed a term that reflected the ongoing research in the content fields that reinforced the value of knowing the best strategies for teaching content (Cochrane, DeRuiter, & King, 1993).

The inaugural issue of Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education in 2000 explicitly acknowledged the value of infusing technology naturally into PCK. When Koehler and Mishra (2005) began writing, talking, and representing their thinking on websites about the importance of TPACK, the professional community recognized the value of envisioning, researching, and describing what the application, or even representation, of TPACK might look like in classrooms.

The research in this article emerged from this foundation of the parts of TPACK and a strong theory that preservice teachers can learn from middle school students. Given the goals to infuse technology at every level of the undergraduate English language arts (ELA) teacher preparation experience and to model TPACK, we incorporated multiple technologies in a collaborative study of The Outsiders with seventh graders in a teacher preparation setting. This article describes a 3-year qualitative study on a teacher preparation approach that places middle school students at the center and interweaves various technologies into the study of The Outsiders.

Teacher Preparation

For years teacher preparation has used K-12 students as subjects; teacher educators have observed them, shadowed them, tutored them, interviewed them, and researched them. Teacher preparation programs have gone from providing no field experience prior to student teaching to requiring various types and consistent experiences with students. Existing approaches often include a progression of courses in a program, a sequence of field experiences, a set number of years required for completion, and recurring themes such as cultural diversity, reflection, social justice, and inclusion. Alternative pathways to licensure may include lateral entry and accelerated or weekend programs. The approach described in this article focuses on placing middle school students at the center of a middle grades teacher preparation program so that preservice teachers learn directly from them.

Field Experience

In the teacher preparation literature, discussions explore the value of extensive field work prior to student teaching (Burant & Kirby, 2002). These field experiences prepare teachers to work with culturally diverse populations (Baldwin, Buchanan, & Rudisill, 2007; Burant & Kirby, 2002), develop reflective practices (Meyers, 2006), and observe master teachers and their students at work. Leaders in the field suggest that these field-based experiences be integrated with course work (Darling-Hammond, 2006; Gallego, 2001; Mewborn, 1999), be community based (Gallego, 2001), and create positive mentor relationships (Darling-Hammond, 2006).

Yet, little research has been conducted on the specific role school students themselves can play in the development of preservice teachers (Cook-Sather & Youens, 2007: Fielding, 2001; Trent, Zorko, & Harrigan, 2006). In fact, the trend in educational research has been for preservice teachers to learn about students, not from them. This pattern of indirectly addressing the student role has been consistent over the past 20 years.

In a profile of empirical studies from 1987 through 1991, Kagan (1992) suggested that interaction with students is beneficial, but suggests that this research is concerned with students as subjects to be studied “in systematic ways” (p. 142). She concluded that interaction with students allows novice teachers to “acquire useful knowledge of pupils” (p. 142). This research may be interpreted as supporting the position that preservice teachers can learn directly from students, but this view was not explicitly expressed.

More recently Lloyd (2005) suggested that preservice teachers can increase their understanding of instruction by reflecting on student experiences. In a case study, Lloyd was primarily concerned with how the preservice teacher’s understanding of the teacher role evolved during field experiences; yet within this discussion, she implied that preservice teachers learn from their students. By pointing to ways the case study subject benefited from “reflection on his students’ comments” (p. 463), Lloyd indirectly pointed to the instructional possibilities of student feedback. She recognized student interaction as valuable, but she did not extend this view to the point of seeing students in an instructional role.

Perhaps the preservice teachers themselves are most aware of the instructional potential of the students. A 2006 study questioned if involvement in a Saturday enrichment program increased preservice teachers’ “understanding of the needs and characteristics of gifted children” (Bangel, Enersen, Capobianco, & Moon, 2006, p. 343). The authors’ expressed intent was to address students as subject matter about which the preservice teachers must learn. However, one of the novice teachers in the study remarked, “The kids continue to improve my teaching style” (p. 353). Although this comment is cited as evidence that the preservice teacher learned about the needs of gifted students, such a comment also indicates that the preservice teacher was looking to the student for guidance on how to teach.

Students as Agents of Discourse

Most research that profiles student participation in teacher education focuses on the value of this interaction as a discursive process. Donnell (2007) contended that preservice teachers and students should learn from one another and that this process is transformative because it is “a kind of teaching practice that transforms learning both for the teacher and for the pupils” (p. 224). The author further explained that “the teacher learns about teaching with and from the pupils” (p. 224). Recognizing the prominence of students in this process, Donnell described them as “active agents in their own learning and in the teacher’s learning about teaching” (p. 225).

According to Donnell, student teachers must be willing to ask and explore questions and be receptive to their students’ responses. One preservice teacher who successfully negotiated this process said, “I take the view I can learn as much from the kids as they can learn from me. You know, that I’m sort of taking a lot of my direction from them” (p. 224). Another student teacher, recognizing that the school experiences of her students provided valuable knowledge about teaching, said, “They give you constant feedback that you can’t get from other people…the most honest and raw feedback” (p. 225). This same student teacher went on to describe learning as a mutual interaction: “They receive the end result of all my schooling and I learn from them” (p. 225).

Wolf (2001) presented research from the Child as Teacher Project in which preservice teachers were paired as reading partners with children of color or children from impoverished backgrounds. She asserted that these children are “exemplary teachers” from whom preservice teachers “have the most to learn” (p. 206). Preservice teachers “must be willing to be the less knowledgeable other, to be the novice and let the child be the teacher” (p. 207). When the preservice teachers “listen to the voices of the children as well as contemplate the impact of their own life experiences” (p. 210), their understandings of teaching, diversity, and individuality grow.

Some of the more extended work on students’ teaching through dialog comes from Cook-Sather (2006a, 2006b, 2007, 2009; Cook-Sather & Youens, 2007), who focused on student voice and student authority within discourse relationships. Cook-Sather’s preservice teachers worked with high school students through a letter exchange program. Following an exchange of letters, the preservice teachers discussed the contents of these letters with their peers, but not with the students themselves.

In “Change Based on What Students Say,” Cook-Sather (2006a) emphasized the importance of shared power between students and teachers. This practice is often seen as a direct contradiction to the traditional model of education, in which authority rests with the teacher. In fact, this traditional model is so firmly established that the participating preservice teachers were often challenged to overcome its influence. Cook-Sather, therefore, noted that “mutually informing and recursive processes” (p. 349) with students helped preservice teachers learn about teaching. Asserting that preservice teachers can learn about teaching by listening to students, Cook-Sather (2009) sought to “[position] high school students . . . as teacher educators” (p. 177). Although she emphasized the importance of recognizing the authority of student perspectives and maintained that preservice teachers can gain pedagogical knowledge by listening to students, Cook-Sather did not specify what this pedagogical knowledge might be.

To date, the literature has only scratched the surface of the powerful potential of placing students as central partners in the development of new teachers. The teacher preparation curriculum and observation experiences are often so full that preservice teachers do not have the time or opportunity to listen and get to know students (Shultz, Jones-Walker, & Chikkatur, 2008) or to hear students’ views on teaching and learning. Recognizing this gap in our own program, as well as the literature, we have discovered the importance of middle school students’ being at the center of the teacher preparation process. The following discussion reveals the evolution of this approach, as exemplified by our research of a project in which middle school students became active pedagogical partners, authorities on how best they learn and should be taught.

The Outsiders Project

The Context

The undergraduate Middle Grades Language Arts/Social Studies program at our university has made a commitment to providing preservice teachers more consistent opportunities to work directly with middle school students, to use various technologies with those students, and to make these experiences an actual part, not an extension, of classes. Therefore, the preservice teachers work in middle schools every year during their undergraduate career; they visit middle schools, tutor students, work one-on-one in a teaching writing class with sixth graders, conduct an inquiry project with middle school students, and participate in the project described in this article—all before they begin the student teaching experience.

To scaffold the preservice teachers’ learning, the program employs a constructivist approach both in the program and courses; we provide scaffolds for our preservice teachers’ experiences with middle school students and require them to reflect and make meaning of these experiences, while faculty do the same. As part of the technology integration, preservice teachers learn to use a variety of technology tools in their learning, planning, projects, and student teaching. Faculty teaching approaches are learner centered, grounded in adolescent development, and models of innovation. The Outsiders Project (TOP), described in this article, is a collaboration between preservice teacher juniors and seniors and their two professors that employs a constuctivist approach to learning, teaching, and using technology.

The Setting

A decade ago the local school system, with shared North Carolina State University and College of Education planning, built a 600-student middle school on the university campus (the Centennial Campus Magnet Middle School; see website at http://ccms.wcpss.net/). The middle school is not a laboratory school, but a regular middle school, complete with a base population, as well as students who must apply through a lottery to attend. This school serves as a university partnership magnet school. The university fulfills its land-grant mission to pilot and share innovative projects and programs through its collaboration with this middle school. It also serves as a conduit for the goal of the Middle Grades English Language Arts/Social Studies program to include consistent experiences with middle school students.

This teacher preparation collaboration is facilitated by a physically connected Friday Institute for Educational Innovation (http://www.fi.ncsu.edu/ ) built by the College of Education. In the Institute is the Discovery Classroom, a space equal to two joined middle school classrooms, a highly flexible room with a soundproof divider wall that can be opened or closed to accommodate large or small groups of students. Students from the middle school enter the Institute on the second floor through a secure double door and walk 30 steps to the Discovery Classroom. The passage provides a physical and symbolic bridge to connect the middle school students and the preservice teachers.

To tap this connection with the partnership middle school, we (two professors, authors Pope and Beal, and two doctoral students) worked with a team of seventh-grade teachers to develop TOP. This project served as the context to research the power of middle grades students as partners and pedagogical experts. We expected that our preservice teachers could gain insight and visions of themselves as innovative teachers by working directly with middle school students—by listening and collaborating with them as both learners and teachers. Thus the driving question for our project and research became “What do preservice middle school teachers learn when middle school students assume the role of pedagogical experts?”

The team chose S. E. Hinton’s young adult classic, The Outsiders, as the content nexus for the project because of its universal themes, its continued appeal to young adults (Gillespie, 2006), and its realistic reflection of adolescent voices, characters, and developmental issues. The themes of identity, friendship, choice and consequence, responsibility, and peer group dynamics resonate with young adolescents and draw them into the text (Erikson, 1968 ). The process nexus for the project included the infusion of multimodal technologies (digital video, music, and Internet research) to engage the students and to model for preservice teachers how technology can be a natural part of English language arts instruction (Pope & Golub, 2000; Swenson et al., 2006).

Motivating students to take ownership of content is often the most challenging element of teaching (Ames, 1990), so we chose music-based teaching (McCammon, 2008) along with video as a centerpiece of TOP. The integration of music can motivate students, reinforce their learning (Barry, 1992; Dowling, 1993), and make content easily accessible, while students also enjoy the process of using music in the classroom (Tinari & Khandke, 2000). We used music as a strategy to enhance motivation and support learning, as a tool to reinforce and extend students’ knowledge of The Outsiders, build a community, and infuse 21st-century technology tools through the use of digital video and publication.

This multimodal approach encouraged students to make meaning through actional, visual, and linguistic resources (Jewitt, Kress, Ogborn & Charalampos, 2001). Further recognizing that today’s students “are accustomed to experiencing the same content portrayed across different media” (Doering, Beach, & O’Brien, 2007, p. 43), we designed the project so that our preservice teachers and middle school students worked together to extend the written text of The Outsiders into a multimedia experience that incorporated writing, music, and performance in a music video as well as an oral presentation. In TPACK terms we interwove what we know about teaching early adolescents and literature with appropriately selected technology that enhances the pedagogical knowledge.

The pedagogical and multimodal approach in TOP also built on social constructivism, in that the preservice teachers would construct meaning in a social context (Patton, 2002), one that emphasized collaboration, interaction, and dialog (Powell & Kalina, 2009). Through this social interaction, albeit in an academic setting, the preservice teachers could create meaning for themselves about middle school students, how they learn, and how students, themselves, might teach. Their talking, discussing, writing, and creating skits with middle school students in this setting served both as representations and ways of thinking.

The Participants

Each year 45 university preservice teachers in the Middle Grades English Language Arts/Social Studies teacher education program participated in TOP. Approximately half the group was composed of seniors in a Literature for Adolescents class (see course website at http://ced.ncsu.edu/eci405/ ) who would student teach full time the next semester. The remaining preservice teachers were juniors in a Teaching in Middle Grades class. The number of university students who participated over the 3 years of this study totaled 135. The total number of middle school students over the 3 years totaled 180. Each year both the preservice teachers and middle school student groups represented diverse cultures.

Before TOP began each fall, the university faculty members met several times with two seventh-grade teachers (one language arts/social studies; one math/science) who worked together on a two-teacher team. The group discussed and reviewed the goals and objectives of the project and crafted a 5-week plan. The middle school students and preservice teachers read The Outsiders before the first official project meeting. Each group clarified any content questions and discussed literary elements. The middle school students were informed that they would explore The Outsiders further with preservice teachers and work collaboratively on activities.

Once the basic plan was created, the middle school teachers provided a list of the students with descriptors about the students’ abilities, personalities, and special needs. The 180 seventh graders (60 each year) who participated in TOP were academically, emotionally, and racially diverse, guaranteeing that our preservice teachers worked with all types of students. The middle school team each year also included students who had a learning disability or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD); some were labeled as gifted; others students had Tourette Syndrome, Asperger Syndrome, or autism.

The professors carefully matched the preservice teachers with the middle school students for the project. Some middle school students needed a same-gender partner because of personal circumstances; others needed either a more gregarious or a more subdued partner. The middle school teachers provided advice when questions arose in this matching process, and sometimes all parties just went on intuition. Ten groups, each including a combination of partners, were formed as a result of collaborating with the teachers to assure camaraderie among students. Only once in the 3 years did the group constitutions change to accommodate potential behavioral issues.

Instructional Plan and Process

The process for TOP is described in Figure 2, the 5-week plan. A few weeks before the project began, the middle school students and preservice teachers exchanged “get-to-know-you” letters. The preservice teachers sent photographs of themselves along with their letters. The preservice teachers received the 5-week plan and prepared for the project in their individual classes.

Week One:

- Get-To-Know-You activities

- Engagement/Reader Response activities (drawn from University students’ study and plans) for discussion of The Outsiders

Week Two:

- Small Groups develop lyrics for The Outsiders song

- Small Groups brainstorm ideas for how middle school students think The Outsiders should be taught

Week Three:

- Small Groups continue to do research, and plan for final presentations on how The Outsiders should be taught

- Group Tapings of TOP song of the year (in style of “Unplugged” music video—i.e., complete with students’ wearing headphones, singing along with recording of song)

Week Four:

- Small Groups continue work on how The Outsiders should be taught

- Group Tapings of TOP song continue

Figure 2. The Outsiders Project (TOP) 5-week plan

On the first day of TOP, middle school students and preservice teachers met face to face in the Institute’s Discovery Classroom at their assigned table sets. Each of the 10 table sets contained several laptop computers, complete with software and wireless connection. The space had an interactive whiteboard, ceiling projection, document camera, and other mobile equipment. The technology infrastructure and tools provided the opportunity for its integrated use throughout the project. Ceiling cameras and dropdown microphones allowed for recording the sessions without distracting the students.

The instructional team began each 1 ½ hour class with a description of the goals and agenda for the day, a review of the prior week, and an explanation of the day’s activities. During the work time, the professors observed, made notes, answered questions, and guided groups. Near the end of the class, the whole group reconvened, discussed what groups had learned, and previewed the next week’s activities. After the students left, the preservice teachers discussed issues that arose, asked questions, and wrote reflections about their learning. The middle school teachers remained for this discussion to answer any questions and to offer insights about particular students. All of this discussion was recorded, and the professors made extensive notes.

As noted in the plan (Figure 2), Week 1 enabled pen pals to meet and groups to form. Preservice teachers then led the groups in get-to-know-you activities and the initial discussions of The Outsiders. This reader-response discussion provided valuable insight into middle school students’ views about the novel and its themes.

In Week 2 the groups discussed the relationship of musical lyrics to poetry and wrote simple lines that described themes and actions of The Outsiders. Groups made notes, discussed possibilities, and then submitted proposed lines for the song that would grow from their discussions; they also began to brainstorm how the middle school students would enact some element of The Outsiders on TOP’s last day. For this portion of the assignment, TOP participants received guidelines to facilitate the discussion and ideas for their plans.

Between weeks 2 and 3 of TOP, instructional team members developed the lyrics of a song based on the phrases, lines, words, themes, and discussions from the class and small group meetings. One member of the team (McCammon) merged the lyrics and created an original tune for the final song. During the 3-year project, we developed three different songs so that each year was different. See the Science (and more) to Music website at http://www.iamlodge.com/beans//?p=63. Both the middle school students and preservice teachers received the song in advance, and the tune was available online, so everyone could practice.

In advance of the Week 3 class, the team set up a studio in the Institute space with recording equipment along with a poster of the lyrics. As each group of 10 preservice and middle school students set off for the studio, they smiled broadly, giggled, skipped, and hopped. Everyone knew the song and was prepared to sing along with the music and pretaped voices.

Week 4 continued much as Week 3. Students researched information to enhance their understanding of The Outsiders, the setting of the novel, and how best to enact some element of the novel. During weeks 3 and 4 groups grappled with literary elements and identified themes and discussed how best to represent these themes. The preservice teachers helped scaffold ideas, paced the discussions, kept their groups on track, and remained alert to individual styles of learning so as to encourage every student to participate.

At the end of weeks 3 and 4, the result was nine “unplugged” music videos—complete with actions, voices, and headsets. The team spliced together portions of each music video into a final product that was premiered on the final day. This process took a number of hours to select representative scenes, make sure all students were present, and merge all the music videos into one.

Week 5 arrived. The music video (Video 1, Video 2, and Video 3) was complete, and the enactments of The Outsiders were ready for presentation. Some groups used costumes, props, and visual aids; others discussed the novel’s themes and challenged the audience of parents, administrators, and other students to consider the meaning of life and death as represented in the novel.

Video 1 (also available on the CED website)

Video 2 (Also available on the CED website)

Video 3 (Also available on the CED website)

Following the presentations, the completed music video premiered. Students who were quiet in the middle school classroom blossomed in the Discovery Classroom space and took their new personas to the screen. None of us expected that a student who never uttered a word in class would become the star of the show, the one making creative moves on the video. Students with special needs actively participated—some by rhythmically hopping, others by strumming an imaginary guitar, dancing, and using facial expressions. Their teachers were amazed, their peers were proud, and their parents could not stop clapping.

Data Sources and Analysis

We conducted a 3-year replication of TOP and our research in order to assure that the outcomes from Year 1 were not idiosyncratic or a one-time phenomena, that the research would be valid because of the extensive time and data sources yielded. Reliability would be enhanced by the replication and close analysis across years.

Therefore, each year we collected and triangulated data from multiple sources that fell within three categories. First, we created weekly field notes based on our observations of the class interactions and activities, the debriefing sessions with middle school students, and the separate debriefing discussion with the preservice teachers. These field notes focused on the preservice teachers and their learning. A second category of data included the preservice teachers’ weekly, individually written reflections and notes about their small groups. A third category included the digitally recorded music video and separate videos of final student presentations. From close observation and review of these digital artifacts, we developed analytic summaries and notes on the content that we used for analysis. These data sources collectively represented social constructivism in action.

The preservice teachers in their interactive, social context with middle school students continuously constructed meaning from their conversations, collaborations, and shared activities (Patton, 2002; Powell & Kalina, 2009). Through their written and oral language the preservice teachers both discovered and represented thought (Vygotsky, 1962/1936). Their learning occurred within a social setting, not as an isolated process.

Both during and at the end of the project each of the 3 years we coded and analyzed the data sources using a constant comparative method following Merriam’s (2009) explanation that “data collection and analysis is a simultaneous process in qualitative research” (p. 165). We combed and re-combed all the field notes, reflections, and digital video notes, keeping in mind the driving question, “What do preservice middle school teachers learn when middle school students assume the role of pedagogical experts?”

As we reviewed and analyzed each data source, we used an open coding method by which we aligned “notations next to bits of data that [would be] potentially relevant for answering [our] research question” (Merriam, 2009, p. 178). Through this open coding process patterns began to emerge. We recorded these patterns, along with significant and representative quotations, in separate memos. The memos also included the number of times particular patterns appeared across the multiple data sources—that is, field notes from the class and debriefing sessions, preservice teachers’ reflections, and notes about the digital videos.

At the end of the designated 3-year research process, we reexamined all data sources as well as the patterns we had determined each year. Through this second analysis, we looked for themes that reoccurred across the years. In this reflective analysis process we generated three broad themes that represented the more narrow subthemes. These themes reflect the meaning the preservice middle school teachers constructed based on their collaboration and interaction with the middle school students.

What We Learned as Teacher Educators

For three years we produced, directed, studied, and analyzed The Outsiders Project (TOP) to determine the impact of these experiences on our preservice teachers and to examine what they learned from the middle school students. As we analyzed our field notes from class and discussion, from the preservice teachers’ weekly reflections, the class video analytic notes, the following themes emerged from the preservice teachers’ own words: They Teach Us About Themselves, They Teach Us About Ourselves, and They Teach Us How to Teach Them.

They Teach Us About Themselves

No matter how many times our preservice teachers heard a lecture, talked about teaching in our classes, or studied a text, nothing quite replaced experiencing a concept firsthand. When one preservice teacher wrote, “I have learned about [developmental theories and] theorists, but nothing helped me to comprehend it more than seeing it first hand,” she reminded us of how critical it is for our preservice teachers to work with middle school students within our classes. Each year our students told us the same things: middle school students want to learn, all students can contribute, and students like books that speak to them.

Students Want to Learn. In no area were the preservice teachers more surprised than in discovering that the middle school students really did want to learn. They wrote that the students are “so much smarter and deeper than I thought” (Marie), “They love to learn, even want to learn” (Shenetta), and “They want to take charge of their own learning” (Marianna). The preservice teachers reported that they were surprised because they did not remember how much they themselves knew as middle school students or how much they wanted to learn, so they assumed students knew little and were not curious. They had also formerly observed classrooms where teachers told students what they needed to know without offering opportunities for students to describe what they already knew.

In TOP we empowered the middle school students by telling them directly that they were our partners in developing the next generation of teachers. We asked them to think of ways to represent important elements of The Outsiders and to contribute lyrics to a song about the novel. This kind of empowerment was new to many of the students, but they quickly adapted to the process of sharing, creating, and exploring possible pedagogies. They were energized both by the activities and their role as leaders. Shona, a preservice teacher, wrote, “Students really do take things seriously and really want to learn; most of the time they don’t think something is ‘dumb’ or ‘uncool’ unless they don’t have something invested in it.”

Alvin, a middle school student, spoke in a debriefing session about the importance of taking responsibility, “We need to listen more in class and [learn] on our own.” In this same session, another student extended Alvin’s remark by adding, “All our ideas are being used [in the song and presentations].” Another reacted, “Yeah. And we learn from the [preservice teachers].” By stepping aside and listening to these middle school students, our preservice teachers discovered that students do want to learn and will actively teach and learn when invited.

All students can contribute. Another lesson our preservice teachers reported they learned about middle school students was that all students can contribute. Because TOP used a combination of such nontraditional strategies as music, digital video, lyrics creation, and student-led presentations, they discovered how all the students could both participate and learn in a variety of ways. They figured out that nontraditional activities benefit all students, not just the most academically successful students.

We purposely did not tell the preservice teachers if any of their partners had any special needs, if they were unusually quiet or shy, or if they had been labeled at-risk or gifted. We did not want to shape our preservice teachers’ attitudes, color their expectations, or influence their behaviors. However, even without this prior knowledge, the preservice teachers picked out the special students for recognition.

Kayla’s experience with Patrick was a case in point. Patrick, diagnosed with ADHD, had low self-esteem and suffered high anxiety. Kayla, without knowing these characteristics, wrote,

My partner Patrick taught me that sometimes all students need is a little push to participate and feel more confident. He has come full circle through this experience. He is not the same student he was five weeks ago. I am hoping I gave him some of that confidence he is now showing.

Barbara worked with a child who was autistic and Caroline worked with a child who had Tourret Syndrome. They both had some challenges; however, they described what they learned in highly positive tones.

Based on the dynamic of our group make-up, we were challenged from day one to make things work. But in the end…we did it! We survived and our lives are most likely better for it! I found my patience level. [I learned about] the willingness of students to work together and the strength we need to work as a collective group. [All the students] came through this process with their hearts and thoughts on their sleeves, ready to put trust for their group on the line. (Caroline)

Barbara also made an important discovery about one of the students:

Not all kids are going to open up to me—not all of them are going to be willing to let me in. But I will always cherish and remember the first student I worked with that I really connected with. I was amazed at his leadership and fairness, his ability to keep his cool, and the way he always tried his hardest. He’ll always be special to me.

The student Barbara described was Juan, a small, self-conscious-about-his-size child who took a strong leadership role with the “special” boys in their group. Both Barbara and Caroline learned that students can be leaders, can help those who are special, and can put the good of the group above their own personal egos.

Another preservice teacher learned that teachers cannot always tell what students are thinking, how they are learning, how much experiences mean to them, or what a difference one teacher can make in a student’s life. In her final reflection Darlene wrote,

I’ll probably have a good cry in the car leaving [today] because Marla’s mom came to me with tears in her eyes saying how thankful she was that I worked with Marla. She told me that she was surprised to see Marla speak in front of such a large group with no problem. She also said that Marla talked about me all the time. I didn’t know what to think. I didn’t even know if Marla even liked me because she hardly said anything.

Comer (2004) suggested that teachers rarely hear words of praise from others because they, themselves, seldom affirm their students. Trapped on an education treadmill that continues to accelerate, teachers may be more intent on covering the material and getting students test-ready than on building and nurturing an environment for learning.

Students like books that speak to them. The preservice teachers studied in the young adult literature class the importance of engaging students in reading and matching students with books. Because of their own experience as readers, they recognized the value of honoring and building on a reader’s personal response before broaching literary analysis. However, they did not quite trust that middle school students would have sophisticated responses to a text if it spoke to them until, that is, they worked directly with the students in TOP. When they read, or reread, The Outsiders, they reported,

“I didn’t really think the students would get into The Outsiders—it [was] written such a long time ago, and I didn’t particularly like it” (Carolyn).

I had never read The Outsiders before and after finishing it, I just did not have a “wow” moment with it. At least until I met my group of students and started talking about the book. Then, I had my moment. Although we were probing them with dozens of questions, their responses put me away. They felt this book because they lived it. They identified with these characters and became their friends and enemies. They planted themselves as people during those times. They thought about reactions they themselves would have had, how things could have turned out differently if certain events had not occurred (Erica).

Both Carolyn’s and Erica’s comments reflect how often our preservice teachers were surprised that the seventh graders connected so strongly with The Outsiders. This realization helped them to see how much they had changed and grown past their own early adolescent years. Without realizing it, they had adopted what Tchudi and Mitchell (1999) described as an “adult standard” (p. 52) view on material. They could never be early adolescents again; therefore, it was hard for them to identify completely with their students.

Although some preservice teachers were not excited about The Outsiders from their adult standard perspective, they found that the middle school students easily related to gangs as a social phenomenon, the characters from both the gangs (the Socs and Greasers), and the universal themes of friendship, family, loyalty, and isolation. They discovered that when students were hooked on a text, they were “capable of sophisticated conversation” (Doris) and could use “their literary knowledge and the language of literature” (Eileen). This result is not surprising to experienced English educators, but preservice teachers were informed by seeing “engagement in action.” In their reflections they frequently remarked that TOP helped them understand how important it is that students relate and find similarities between a book and their lives.

To discover specifically how The Outsiders might relate to their lives, we asked the middle school students to consider the best ways to represent the novel today. In their groups they and the preservice teachers explored this concept. To the amazement of the preservice teachers, the students had numerous ideas, but they were also curious and had “big questions” (as defined by Beane, 1997) about the novel and its context—the setting, author, music, fashion, technology, entertainment, and historical events of the times. Using the laptops on their tables, they explored these topics, listened to the music of the times, and even discovered the unexpected. They used websites like Ask.com and inquired of older adults, “What could you buy for a dollar in early 1960?” “What kind of dances did you do at the sock hop?” Clearly they were engaged by The Outsiders’ setting and context.

The easy access of computer technology allowed students to pursue answers to their questions within the class, to use the Internet to satisfy their curiosity in a natural way, and to gain knowledge about the historical setting of the novel. In this instance the students were TPACK representatives, and the pedagogy was implicit in their questions and action.

From witnessing firsthand students’ genuine curiosity about a book, our preservice teachers learned to trust their students, to have confidence in their ability to “run with a book,” to trust them to learn, to want to learn. They also learned not to underestimate students These realizations may seem evident to experienced teachers and teacher educators, but our preservice teachers were developing; they were becoming teachers; they were finding new selves as they came to understand and know early adolescents. These epiphanies about the intertwined nature of text and engagement, reader response, and literary insight emerged from their sustained work with middle school students, much more than it could have from the young adult literature class alone.

They Teach Us About Ourselves

Another prevailing theme in our data analysis over 3 years and 135 preservice teachers was how instrumental the middle school students were in guiding the development of the next generation of teachers. One highly organized, focused student, reported that “not only have the students changed, but we have changed ourselves” (Caroline). She, like many others, wrote and talked about how they came to know themselves. They could both feel and see how they had shifted—from students to teachers, from doubters to believers in themselves. The students helped them not only develop but recognize how they themselves, as developing teachers, changed and grew.

The Value of Patience. The preservice teachers frequently described in their discussions and reflections how they had discovered in TOP the value of patience. From the middle school students they learned that a student’s “getting on my last nerve” (Sherika) can really mean that the student wanted attention. Recognizing this need, Sherika gave her partner time to tell her about herself and, by the end of TOP, wrote “I LOVED THIS!”

Another preservice teacher explained that once she loosened up and stopped “thinking so much about ‘should I say this? Is it okay to do that?’ it flowed so much better” than when the “conversations were strained and the silences long” (Susan). On the other hand, by discovering the importance of being herself, Susan also discovered her “boundaries as a teacher.” She found her voice of authority and learned to use it as well as judge when it was appropriate. Similarly, Cecelia wrote in her final reflection, “I am surprised by how calm I can be and how there is not much that takes me to a breaking point.” She became, in her own words, a “strong, confident, fun, and patient person.” The brand of patience the preservice teachers described had more to do with them than it did the middle school students. They found that they could, indeed, be impatient—much to their surprise. They also discovered that they could bide their time and persevere.

The Ability to Adapt. Another quality the preservice teachers learned about themselves was their own ability to adapt. Ken explained one week,

If what you’ve planned isn’t working, adapt. You have to fit what works best for your students. While we were working, we had to change a bunch of different times. We taught “on the fly” and it had a lot of positive outcomes.

In this comment he alluded to how he and his peers decided to try a different strategy to engage all the students in their group.

What Ken reported aligned with Leslie’s discovery that she learned “to step back and get a different view of the circumstances.” A mature, introspective student, Leslie said she worked “hard to let go and share control…to listen…and take direction from others.” Working closely with the middle school students, from whom she learned to deal with changing moods and personality clashes, and her colleagues gave her ample opportunity to step back, review the occurrences, and adapt her own responses and behaviors. Delia, too, reported that she “learned to let other people lead for once…doing and watching are both so important in the learning process.” And that adaptation paid off in the success of her group’s interaction, the fact that she “learned how to be a better group member, a better teacher, and most importantly a better person. If you learn to listen and adapt, you get back so much more than you give” (Tara).

Our preservice teachers learned in TOP the importance of adaptive teaching (as defined by Darling-Hammond, 1999). Adapting requires accepting others, recognizing one’s own need for control, clearly seeing others’ needs, and being able to shift and accommodate. It sometimes even requires that we “pick [ourselves] up each day and put on an excited face…and rebound from a bad day.” (Lana). They remarked time after time that they had found the experience “life changing” and personally informing.

Okay…so maybe this wasn’t as much about them [and their learning] as it was about me—this time. I learned to get over myself, stop whining, and remember why I’m here. I love kids! Next time I can add, grow, give more and do just about anything with the knowledge I’ve gained. (Julie)

We have always told our preservice teachers that becoming a teacher is as much about learning about ourselves as it is about learning about students, learning to teach, or learning to thrive in an educational environment. The preservice teachers discovered some of their limitations, attitudes that held them back, and their ability to shift so as to adapt and accommodate others—both students and peers. Most importantly, they learned that “It’s not about me!” (Morgan) Because middle school teachers work closely with other content teachers in teams to integrate curriculum and to support students, this lesson was particularly appropriate and critical.

Commitment and Confidence as Future Teachers. Pervasive in their written reflections and class discussions were comments like the following.

“I truly believe now that ‘I can do this!’” (Julie)

“I’m completely convinced I belong in a middle school classroom.” (Erica)

“I am definitely going into the right profession: no other job in the world would give me the kind of joy that I felt being with those middle school youngsters.” (Cecil)

“Teaching is my true calling. The joy I felt from my students and this experience made me realize how much I love working with kids.” (Katie).

Such responses reflect the fact that the preservice teachers discovered themselves with middle school students. They came to believe the middle school students who said, “[These preservice teachers] are awesome!” Another middle school student said in our debriefing session, “This [project] makes me want to be a teacher someday.”

Although these comments reappeared across the 3 years of the study, we are aware of the halo effect that can emerge with the completion of a challenging, yet rewarding experience. We found this response recurring so frequently each of the 3 years that we could not overlook it. With the continued attrition of young teachers, we know we have to do everything we can with our preservice teachers to build their confidence on a firm foundation. Just telling them how much they know, giving them feedback on lesson and unit plans, and providing our best guidance will not be enough. They need to have real experiences with early adolescents; they need to see how they can learn both from and with their students; they need a foundation not easily shaken by the vast array of students with whom they will work, the leadership gap that exists in some schools, and the constant political and public barrage about achievement scores.

Having the kind of authentic, challenging, and boundary-stretching experience our preservice teachers had with TOP can fortify them, help them adapt when they need to, see students as their partners, and be strong in their commitment. We cannot guarantee their retention, but we can provide an authentic, rich experience to confirm their commitment. We want them to have a memory, a touchstone for their futures—a place they can revisit in their minds when they are discouraged or in doubt.

The Value of Continuous Learning and Teacher Leadership. The preservice teachers realized the excitement and challenges of teaching and learning as a lifelong sustaining process. Linda, for example, talked in class about how it is “important to be a continual, constantly learning teacher.” Allison in her reflections explained her commitment to students and their shared futures:

I know that middle school students are capable of anything in the world. I want to show them how capable they really are. While I am opening their eyes to the world, I want them to open my eyes to things that may not be clear to me. As a teacher, I know I will continue to learn, even if I am not always a student.

Sherika, who exuded confidence in our classes and came from a family of educators, became more frightened and concerned every day during TOP as she neared her student teaching semester. She worried that she would not know enough, feared she would not be able to engage students, and quaked at the thought that she would not be able to remember all she had studied. At the end of TOP she revealed an important insight that she gained from the work with her seventh-grade partner: “I was becoming overwhelmed with how much I needed to know as a beginning teacher, but I now realize that teaching is a learning process.” The students are there as partners; they are, in fact, positive enablers. Delia’s awareness that both “doing and watching are important in the learning process” enabled her to relax a bit and trust her ability to watch and learn, to be a continuous learner. No teacher ever knows everything, but the journey of teaching and learning with and from students can energize, motivate, and retain teachers.

Acknowledging the power of ongoing learning as a critical factor for teacher leadership (as described by Katzenmeyer & Moller, 2001), we found that many of our preservice teachers came to recognize themselves as leaders in TOP. Those who choose to become teachers often have innate leadership qualities, but we did not anticipate that our students would reach this awareness about themselves during the TOP experience. Many realized that they want to take control and make things work in groups, while others reported that for the first time they felt like leaders. Letitia was rewarded by her recognition that she felt “more mature” because she assumed a leadership role. For her, becoming a leader meant taking the reins, not depending on the professors, yet giving some leeway to the students. On the other hand, some struggled to remove themselves from the “taking over” mode. Leslie reported that she was “working very hard at letting go, sharing control and responsibilities, listening to [her] colleagues, and [taking] direction from others.” Others, like Barbara, reached the conclusion that “no matter how much I may try to take a back seat, I am a leader. I can’t help it. It is just who I am.”

Even as these preservice teachers grew to see and accept themselves as leaders, their understanding of this concept also evolved. Prior to this experience they had thought of leaders as people who took charge and made things happen. As they worked in their TOP groups, they realized that they needed to share that role with their peers and with students. They experienced the value of shared leadership: “I learned that I need [the students] as much, if not more, than they need me” (Delia). And Barbara reported learning in TOP that she could recognize and support students as leaders. Her partner, Juan, guided their large group, and Barbara was pleased to share that role: “I hope I will be able to lead my students like Juan led the students in our group.” She and many others expressed relief that they could share leadership and learning (as recommended by Barth, 2001), and that they could count on both their peers and the students.

They Teach Us How to Teach Them

In the young adult literature class our senior preservice teachers read numerous young adult books; they studied and practiced reader-response through electronic literature discussions, developed comfort in using the language of literature, and learned how best to engage and guide middle school students as readers. They had also used video technology, online research, and presentation software in class. However, nothing quite surpassed the face-to-face, direct work with middle school students on a novel. “What better way to learn about teaching young adult literature than to learn from early adolescents themselves” (Shanika). They reported that they experienced firsthand how students want to be engaged through 21st-century tools, that there are endless ways to teach a novel, and that students can be in charge of their own learning.

Students Want to Be Engaged With Texts Through 21st-Century Tools. Although The Outsiders was written 40 or so years ago, the preservice teachers quickly discovered that the text appealed to the middle school students because it presented characters and themes to which they could relate. However, the preservice teachers also learned that these middle school students wanted to enter the world of the text by using the 21st-century tools of their own world.

Throughout TOP we employed such tools as online research, musical lyric writing, music, digital video production, and performance as strategies to motivate and engage students in studying The Outsiders and extending their connection to the novel and its messages. When students had questions about the setting of the novel, they sought to answer these questions through online research. For example, when the students read about the music, clothing, and cars in The Outsiders, they wanted to hear the music and see the cars and clothing. They chose to experience these text elements through online resources.

As the students engaged with the text, they used technology along with their preservice partners. While they worked to create their own song lyrics for The Outsiders, students talked to the preservice teachers about iPod playlists and their criteria for music choices. When the groups’ lyrics were compiled into a complete song, students had digital access to the song; therefore, they could listen to the song away from school as well as in class. As a result of this availability, they were prepared to perform their group’s song and create a digital video. They also expected that their video would be published and accessible to them.

Preservice teachers and the middle school teachers noted that students who were often shy or nonparticipants in class found a space in TOP where they could contribute actively; other students who were considered “challenged” found ways to participate in their own ways. Some sang, jumped, and spun in place during their music video; others stood rigidly in one place but were determined to be a part of the video; and even others smiled broadly and sang out fully. Our recorded observations noted the value of full inclusion in middle school classrooms. Not one student was marginalized or considered different; students worked and moved together; and students each left their recording event with smiles or laughter.

There Are Endless Ways to Teach a Novel. Although they knew that many strategies exist for opening literature to their students, preservice teachers were struck by the degree to which the middle school students could not only recommend but also demonstrate their knowledge. They observed, “If you give students options on how they want to [enact] material, then they will come up with more stuff than you ever could have imagined” (Jane). The middle school students themselves reported that they benefited from “group work and moving around,” that they liked to “bring in new ideas and have open discussions,” and that “they want to participate” in their own learning. Tara made a pedagogical leap when she wrote in her final reflection that asking students how they might like or want to learn about a book is “a great method for teaching literature because students get to be the teachers.” In fact, Tara wrote to us during her first year of teaching that she had successfully used the approach of having students be teachers in her own middle school language arts classroom.

Students Can Be in Charge of Their Own Learning. The preservice teachers found they could serve as facilitators, just as they had led and guided the middle school students in their groups, because the teacher does not have to do everything. They also experienced firsthand how kinesthetic, intrapersonal, and spatial middle school students are—how much they prefer interaction and involvement, group research and presentations, and projects to display their learning. “The excitement produced from bouncing around to a song prompted the most focused energy on literature I have observed in my own [varied] classroom experiences [as a student and preservice teacher]. That hook is essential” (Abbie). They learned that

literature does not have to be taught in a traditional manner. Before this project, I would have never thought a song could help kids learn about a book. However, these students did more than just memorize a song; they understood what it was talking about, and it helped them to get some of the major points [of the novel]. (Lelia)

By reflecting on what they saw the middle school students learn, the preservice teachers discovered that action products uncovered and revealed middle school students’ knowledge of The Outsiders, their grasp of character development, and their understanding of such literary concepts as theme, conflict, and reliable and unreliable narrators.

As we debriefed each week and at the completion of TOP with the preservice teachers, we listened intently as they moved from questions and concerns in our first days to evidence of learning they witnessed as the project moved along. They described how the middle school students were learning about history and research techniques as they searched the Internet for answers to questions about America in the 1950s. They learned to narrow their searches, use appropriate key words, and look past the first few sites listed on a Google search. They also practiced asking questions of primary sources in true historian style. Their curiosity and questions were stimulated by the novel itself, its setting, and such references in the text as drive-ins, parks, music, and cars. From witnessing this natural curiosity, the preservice teachers grasped the fact that “it is okay not to have all the answers [as a teacher]; some things students need to investigate and learn on their own so that they can teach others” (Sherika). “We gave them responsibility, and they ran with it” (Mindy), and letting them run with an idea paid off in both the process and final product.

Challenges and Opportunities

No project or teaching experience occurs without its challenges and issues, and that was true for TOP as well. We had some middle school students who needed more attention than others; we had preservice teachers who complained about each other; and we had groups that did not function as expected on any given day. What we and our preservice teachers learned again and again, however, is that teaching requires perseverance and a commitment to the students first.

To assure that the middle school students stayed focused on TOP, we worked as a team to counter immediately any potential problems that arose throughout our 5 weeks. For example, when a student or pairs of students went to the water fountain or the rest room, they were quietly accompanied by an adult. When Paul, a boy with autism, constantly moved in and out of his chair, monopolized the conversation, and frequently sought to use the computer at inappropriate times, the preservice teachers and the other middle school students stayed firm. When he said, “I don’t like to wait. I just want to start,” the preservice teachers responded, “We’ll get to that in a few minutes. We need you to focus right now.” Even one of the middle school students intervened on occasion, “Remember to be patient, Paul.”

During our weekly debriefing sessions after the middle school students left the classroom, the preservice teachers voiced their concerns and challenges. Alicia, normally confident and enthusiastic, reported one week, “This is really hard. It’s hard to keep all the kids focused at the same time, and I have to be careful of their feelings.” This challenge surprised her, but she and her partners kept returning each week with new strategies and renewed patience. At the end of the project she described herself as “thrilled” with their group’s results, especially in light of where they started. She experienced that teaching requires perseverance and acceptance.

Sherika, too, said after another session, “This was a bad day. Two of them wanted to talk all the time. They got on my last nerve.” Interestingly, her preservice partner Cecelia wrote about that same day, “I am surprised by how calm I can be and how there is not much that takes me to the ‘breaking point.’ I don’t let it get to me. Some arguments are just not that important.” In our field notes that day, we noted that Sherika and Cecelia’s group was moving their process along quickly and efficiently and that their middle school partners were actively engaged. Obviously, our perspectives varied. In contrast to her earlier complaints, Sherika wrote at the end of the project, that she “loved” her experience with the students; she concluded that students can create a “final product as long as [the teacher] gives the foundations and scaffolds, and I look forward to using this methodology in my class.”

On occasion we had preservice teachers who wrote in their weekly reflection that they felt alone, that their peers were not pitching in to help as much as they had expected, that they were disappointed in their team members. When that situation occurred, we made a point of discussing in class the value of learning to work with colleagues, of resolving work balance, and the application of these skills when they become middle school teachers working on teams. We then monitored the teams to see if they resolved their issues or if we needed to intervene. We never found it necessary to intervene, as all the groups figured out how to keep every person involved and the work load balanced.

An observer of this process might say that the university and middle school teacher team would not allow this project to fail, and that observer would probably be right. The team collaboratively planned the entire project, carefully reviewed and prepared each week, provided a scaffold for preservice teachers’ weekly tasks, problem-solved together, and heard all perspectives. Each week the teacher team reinforced the fact that teaching is not just for today; the frameworks and attention brought to the task today pay off tomorrow. We also discussed the importance of taking a long view, keeping an eye on the students and their learning. And both the teacher team and preservice teachers said over and over, “This is not about us; this is about them.” By working together the preservice teachers learned to step outside themselves, to recognize when the issue was their own insecurity, impatience, or unrealistic expectations, and to ameliorate circumstances to assure the success of their student partners.

Principles for Teacher Education Programs

Although our access to the Institute and its adjacent middle school supported the implementation of The Outsiders Project, the principles of teacher education that emerged from this project are not unique to our setting and can be applied in other teacher preparation programs. In order to maximize the potential for K-12 students to become pedagogical partners in teacher education, teacher educators need to create field experiences that allow preservice teachers frequent and ongoing opportunities to work with students, facilitate the development of relationships between preservice teachers and students, and present opportunities for preservice teachers and students to participate collaboratively in authentic experiences.

Frequent and Ongoing Opportunities to Work with Students. A critical element of this project was providing preservice teachers with an extended experience working with the same middle school partners. The structure of this project allowed for preservice teachers and middle school students to meet regularly over a 5-week period. Preservice teachers were able to gain more than a snapshot image of their partners; they were instead able to interact with these students over time and to move beyond initial impressions to form more complete understandings of the students. Equally important was allowing sufficient time for reflection; as preservice teachers gave consideration to their interactions with students, they were able to see for themselves how their knowledge of middle schools students and how they learn had evolved.

Development of Relationships. As is demonstrated in the weekly reflections of the preservice teachers, their understandings of how students learned resulted from their understandings of who the students were. The preservice teachers began TOP with their focus on the students, not the end product of the project. The early activities that supported their getting-acquainted process allowed them to create relationships with their middle school partners. As those relationships grew, the middle school students began to share more openly with the preservice teachers and to reveal what they needed to be successful. Because they had come to know and trust the preservice teachers, they felt safe revealing what they knew and, thus, were able to take on more fully their role as pedagogical experts. In turn, the preservice teachers came to understand the importance of caring and realized that they were more effective when they were motivated by respect and genuine concern for their middle school partners.

Participating Collaboratively in Authentic Experiences. The preservice teachers and the middle school partners worked together in TOP to write music lyrics and create songs based on their common understandings of a book they had read. The preservice teachers understood that the goal was to create a project together and not to tutor their partners; they were to work side-by-side as equals, not as authorities. As time progressed and relationships grew, the partners became increasingly involved in writing and performing their lyrics and in the creation of their music video because it was a authentic experience, the type of learning experience that “deepen[s] the learning process and help[s] students construct a personal meaning” (Daniels & Bizar, 2005, p. 194). All members of the group were responsible for integrating technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge in a seamless process that supported their goal of creating a music video. The authenticity of the experience was as significant for the preservice teachers as for the middle school students. Through this type of collaboration, the preservice teachers could interact with their partners and be participants in the learning process.

Middle School Students as Pedagogical Partners

When our team began the first TOP, we thought that middle school students could become an integral part of our middle grades teacher preparation program before student teaching. We did not know the extent to which they could become full-fledged teacher educators. We discovered that middle school students are, indeed, great mentors (as suggested by Cook-Sather & Youens, 2007). They are insightful and talented; they can talk about teaching as if they have peeked into our classes.

This view conflicts with some of the prevailing myths about middle schools that suggest they are merely holding tanks, places to keep young people ages 12-14 until they grow into high school students, and that middle school students cannot know or do anything (Arnold, 1991). Our research and experience with TOP counters this view. Middle school students have much to share and can embrace the challenge of developing the next generation of teachers. They like being partners with in this process, know how to describe the ways they best learn, and have many suggestions. There is great power in listening to these students (as noted by Cook-Sather, 2006a; Pratt, 2008), for they know more than we expect about effective teaching and their own learning.

Middle school students have typically been silent partners in teacher preparation; their voices have been underrepresented. They have been subjects for discussion, observation, study, and research. However, as a profession teacher educators should move students past this traditional role, embrace them as co-teacher educators, bring them early into the teacher preparation process to inform, demonstrate, and explain how they learn and wish to be taught. This focus would necessitate a shift in the way teachers are prepared, for it would bring university-school collaborations to new levels, encourage and support innovation as well as genuine partnerships.

This approach now defines us as teacher educators. We cannot see ourselves returning to the time when we did not have middle school students as TPACK partners, for we cannot prepare the next generation of middle school teachers without them. Preservice teachers need to experience with middle school students the authentic, natural integration of technology in content and pedagogy. With these opportunities they learn about themselves, about middle school students, and about how to teach them.

References

The AACTE Committee on Innovation and Technology (Ed.). (2008) Handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK). New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Ames, C. (1990). Motivation: What teachers need to know. Teachers College Press, 91(3), 15-21.

Arnold, J. (1991). A curriculum to empower young adolescents. Midpoints Occasional Papers, 4(1).

Baldwin, S. C., Buchanan, A. M., & Rudisill, M. E. (2007). What teacher candidates learned about diversity, social justice, and themselves from service learning experiences. Journal of Teacher Education, 58(4), 315-327.

Bangel, N. J., Enersen, D., Capobianco, B., & Moon, S. M. (2006). Professional development of preservice teachers: Teaching in the Super Saturday program. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 29, 339-361.

Barry, N. H. (1992). Project ARISE: Meeting the needs of disadvantaged students through the arts. Auburn, AL: Auburn University.

Barth, R. (2001). Learning by heart. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Beane, J. (1997). Curriculum integration: Designing the core of democratic education. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Bull, G., & Bell, L. (2009). TPACK: A framework for the CITE Journal. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 9(1). Retrieved from https://citejournal.org/ vol9/iss1/editorial/article1.cfm

Burant, T. J., & Kirby, D. (2002). Beyond classroom-based early field experiences: Understanding an “educative practicum” in an urban school and community. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18, 561-575.

Cochran, K.F., DeRuiter, J. A., & King, R.A. (1993). Pedagogical content knowing: An integrative model for teacher preparation. Journal of Teacher Education, 44(4), 263-272.

Comer, J. P. (2004). Leave no child behind: Preparing today’s youth for tomorrow’s world. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Cook-Sather, A. (2006a). “Change based on what students say”: Preparing teachers for a paradoxical model of leadership. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 9, 235-358.

Cook-Sather, A. (2006b). Sound, presence, and power: “Student voice” in educational research and reform. Curriculum Inquiry, 36, 359-390.

Cook-Sather, A. (2007). Direct links: Using E-mail to connect preservice teachers, experienced teachers, and high school students within an undergraduate teacher preparation program. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 15(1), 11.

Cook-Sather, A. (2009). “I am not afraid to listen”: Prospective teachers learning from students. Theory Into Practice, 48(3), 176-183.

Cook-Sather, A., & Youens, B. (2007). Repositioning students in initial teacher preparation. Journal of Teacher Education, 58, 62-75.

Daniels, H., & Bizar, M. (2005). Teaching the best practice way: Methods that matter, k-12. Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers.

Darling-Hammond, L. (1999). The case for university-based teacher education. In R. Roth (Ed.). The role of the university in the preparation of teachers (pp. 13-30). Philadelphia, PA: Falmer Press

Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Constructing 20th-century teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 57, 300-314.

Doering, A., Beach, R., & O’Brien, D. (2007). Infusing multimodal tools and digital literacies into an English education program. English Education, 40(1), 41-60.

Donnell, K. (2007). Getting to we: Developing a transformative urban teaching practice. Urban Education, 42, 223-249.

Dowling, W. J. (1993). Psychology and music: The understanding of melody and rhythm. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Erikson, E. (1968). Identity, youth, and crisis. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Fielding, M. (2001). Students as radical agents of change. Journal of Educational Change, 2, 123-141.

Gallego, M. A. (2001). Is experience the best teacher?: The potential coupling of classroom and community-based field experiences. Journal of Teacher Education, 52(4), 312-325.

Gillespie, J.S. (2006). Getting inside S. E. Hinton’s The Outsiders. English Journal, 95(3), 44-48.

Grossman, P. (1990). The making of a teacher. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Jewitt, C., Kress, G., Ogborn, J., & Charalampos. T. (2001). Exploring learning through visual, actional and linguistic communication: The multimodal environment of a science classroom. Educational Review, 53, 5-18.

Kagan, D. M. (1992). Professional growth among preservice and beginning teachers. Review of Educational Research, 62, 128-169.

Katzenmeyer, M., & Moller, D. (2001). Awakening the sleeping giant: Helping teachers develop as leaders (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Koehler, M. J., & Mishra, P. (2005). What happens when teachers design educational technology? The development of technological pedagogical content knowledge. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 32(2), 131-152.

Lloyd, G. M. (2005). Beliefs about the teacher’s role in the mathematics classroom: One student teacher’s explorations in fiction and in practice. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 8, 441-467.

McCammon, W. L. (2008). Chemistry to music: Discovering how music-based teaching affects academic achievement and students’ motivation in an 8th grade science class. (Doctoral dissertation, North Carolina State University).

Merriam, S.B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mewborn, D. (1999). Learning to teach elementary mathematics: Ecological elements of a field experience. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 3, 27-46.

Meyers, E. (2006). Using electronic journals to facilitate reflective thinking regarding instructional practices during early field experiences. Education, 126, 756-762.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A new framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017-1054.

Patton, M.Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pope, C., & Golub, J. (2000). Preparing tomorrow’s English language arts teachers today: Principles and practices for infusing technology. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education 1(1). Retrieved from https://citejournal.org/vol1/iss1/currentissues/english/article1.htm

Powell, K.C., & Kalina, C.J. (2009). Cognitive and social constructivism: Developing tools for an effective classroom. Education, 130(2), 241-250.

Pratt, D. (2008). Lina’s letters: A 9-year-old’s perspective on what matters most in the classroom. Phi Delta Kappan, 89(7), 515-518.

Schultz, K., Jones-Walker, C.E., & Chikkatur, A.P. (2008). Listening to students, negotiating beliefs: Preparing teachers for urban classrooms. Curriculum Inquiry, 38(2), 155-187.

Shulman, L. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57, 1-22.

Spires, H., Wiebe, E., Young, C. A., Hollebrands, K., & Lee, J. (2009). Toward a new learning ecology: Teaching and learning in 1:1 environments (Friday Institute White Paper Series). Raleigh, NC: North Carolina State University.

Swenson, J., Young, C., McGrail, Ewa, Rozema, R., & Whitlin, P. (2006). Extending the conversation: New technologies, new literacies, and English education. English Education, 38(4), 351-369.

Tchudi, S., & Mitchell, D. (1999). Exploring and teaching the English language arts (4th ed.). New York, NY: Longman.

Tinari, F.D., & Khandke, K. (2000). From rhythm and blue to Broadway: Using music to teach economics. The Journal of Economic Education, 31(3), 18.

Trent, A., Zorko, L., & Harrigan, A. (2006). Listening to students: “new” perspectives on student teaching. Teacher Education and Practice, 19(1), 55-70.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1962). Thought and language. (A. Kozulin, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (Original work published in 1934.)

Wolf, S. (2001). “Wax on/wax off”: Helping preservice teachers “read” themselves, children and literature. Theory in Practice, 40, 205-211.

Author Information

Carol Pope

North Carolina State University