Recent developments in teaching and learning have helped history become a subject based on varied media. A succession of authors have claimed that the effective application of information and communication technology (ICT), including multimedia CD ROMs, largely depends on the historical sources they contain and the associated learning tasks (Haydn, 1996; Schick, 1996). These tasks should support an inquiry-based methodology, as students justify the conclusions reached from their research into the questions they have asked (Calandra & Lee, 2005). Much current interest involves the incorporation of authentic learning based on real-life challenges that are characterized by their multidisciplinary perspectives, open-endedness, multiple possible solutions, and team work. (Herrington, Reeves, Oliver, & Woo, 2004).

Moreover, greater prominence is given to cross-curricular approaches where several subjects contribute to a theme. For example, Britain’s war dead are remembered each year on November 11, with some schools using this occasion as the basis of a cross-curricular project on Remembrance Day, drawing on subjects such as history to provide insights into the First World War and English to discuss war poetry. The Scottish programs examined in this article demonstrate these principles in action and provide support for trainee teachers as they help school students think critically about the past. However, this study has a wider focus, as it discusses four areas, namely student evaluation of the primary sources, the impact on cross-curricular activities, skill development, and observations of the authentic challenges. It is also based on the relatively unusual experience of research into the historical topics leading to the design, development, and production of a series of multimedia CD ROMs.

History Education in Scotland

Scottish schools encompass the seven-stage primary school from ages 5-11 years leading into the six-stage secondary school from ages 12-17 years, with the curriculum largely based around subjects (e.g., history, geography, chemistry, and mathematics). Until the current reform of the primary and secondary curriculum, known as A Curriculum for Excellence (Learning and Teaching Scotland, 2010), the history curriculum from Primary 1 to Secondary 2 lay within the environmental studies component of the 5-14 program. Broad parameters were established with content drawn from five main historical eras covering Scottish, British, European and world themes (Learning and Teaching Scotland, 2000). Schools were free to choose topics within these themes, but a core of popular topics emerged including Skara Brae, Romans, Ancient Egypt, Vikings, and medieval Scotland, especially the Wars of Independence, voyages of discovery, and Mary, Queen of Scots.

In many respects, A Curriculum for Excellence follows the pattern set in the 5-14 program by identifying broad student outcomes rather than setting out specific content. These outcomes give more emphasis to Scottish history, as in the following example from Level 3, Primary 7/Secondary 1:

I can make links between my current and previous studies, and show my understanding of how people and events have contributed to the development of the Scottish nation (Learning and Teaching Scotland, 2009, p. 3).

The outcomes emphasize that Scottish topics should be balanced by those focusing on British, European, and world themes. The outcomes will not radically alter history courses that currently satisfy many outcomes as they relate to content, but cross-curricular or themed topics are expected to gain more of a foothold.

At the end of Secondary 2 (student age 14), history becomes an optional subject with Standard Grade History providing the national syllabus featuring Scottish, British, European, and world themes largely drawn from the late 18th century to the 1960s. The course places considerable emphasis on an inquiry/investigative methodology in which students also evaluate sources “with reference to their historical significance, the points of view conveyed in them and to the relevant historical context” (Scottish Qualifications Authority, 2009, p. 12).

In the final two years of secondary schooling, subjects including history are offered at different ability levels, from access to higher and advanced higher. History remains an optional subject with most students at these stages taking the higher level course for students in Secondary Year 5, where the content continues to balance Scottish, British, European, and world themes covering topics from the Medieval, Early Modern, and Later Modern periods.

Therefore, until the end of Secondary 2, schools are relatively free to decide on course content, with syllabi thereafter providing a range of options. These options include Scottish and world themes. However, at every level history education develops knowledge, understanding, and skills, with particular emphasis on an inquiry-based methodology encompassing source evaluation.

This emphasis on balancing the development of knowledge and understanding with an inquiry pedagogy using primary and secondary sources can be traced back to the late 1960s and early 1970s, when traditional approaches were increasingly challenged for providing “the school learner with nothing beyond a set of imperfectly understood facts and ill digested notions” (Fairley, 1970, p. 7). Fairley helped steer history teaching in new directions with an emphasis on source work, activity methods, patch history, and field studies. These and other developments in Scotland find parallels and have been influenced by advances in many other countries.

Analysis of primary sources is essential in helping students understand the structure of history, its methods of inquiry and the ways new ideas are added (Shulman, 1987). “Without an understanding of what makes an account historical,” argued Lee (1991), “there was nothing to distinguish such ability from the ability to recite sagas, legends, myths or poems” (p. 45). Consequently, analysis and interpretation of primary sources is central to history syllabi on both sides of the Atlantic (Seixas, 1993, 1996, 1997, 1998).

This emphasis on supporting students in the process of framing questions, researching for answers, and presenting conclusions has found more general agreement (Calandra & Lee, 2005; Calder, 2006). However, a feature of the Scottish programs is that their learning tasks help students develop a wide range of intelligences from the literary to the natural world (Gardner, 1999). In this way, history develops skills across disciplines (Riley, 1999), since it sits in the middle of a web with strands expanding through the curriculum. This cross-curricular dimension has been an important aspect of the Scottish programs, but one finding is that interdisciplinary activities depend upon a sound knowledge of a discipline such as history.

Multimedia in History

Developments in history education help provide criteria for multimedia to enhance learning. ICT, including multimedia CD ROMs, is a flexible platform on which to locate primary and secondary sources (Lee & Clarke, 2004; Swan & Hofer, 2008), which would often be difficult to collect and manage through traditional models of teaching (Schick, 1996). These sources include photographs, film, firsthand accounts, maps, secondary interpretations, and databases, with the databases helping students locate information, test hypotheses, and answer questions (Taylor & Young, 2009). However, multimedia must be more than an information bank, as it should support interactivity beyond moving the student through the program in providing information that can be applied to other problems and by asking questions that challenge the user to “think differently about the past” (Schick, 1995, p.11). Haydn (1996) referred to this task as the “problematization” of learning (p. 15).

Wiley and Ash (2005) used their review of research into multimedia in history to establish three general criteria if new technology is to enhance learning, namely, an inquiry-based methodology, highly structured activities, and teacher instruction “in the way historians use, judge, and interpret historical data” (p. 385). These criteria underpin the development by the author and a computer programmer of a series of multimedia resources on themes within Scottish history. The resources are delivered through CD ROM rather than the Internet, since I do not hold copyright on some of the sources and obtaining permission to place them online was not possible. Most notably, posting to the census databases online would have undermined those provided online by the Office of the Queen’s Printer in Scotland. The resources were pulled from the following documentary source collections:

- Doon the Watter (1996) takes as its theme holidays taken along the River Clyde, going doon the watter, in late Victorian Scotland. Traveling doon the watter epitomized the growth of popular culture following large scale urbanization.

- Auld Reekie and the Dear Green Place (2001) compares life in Victorian Edinburgh (Auld Reekie) and Glasgow (The Dear Green Place).

- Changing Scotland, Scottish Society 1880-1939 (2003) analyzes changes in Scottish society in the wake of industrialization and urbanization.

- Barnhill (2005) allows students to study the Victorian response to the growing numbers of urban poor through the Poor Law Amendment Act and the resulting network of Poorhouses.

- Ruled by the Seasons (2009) is based on the journal kept between 1879 and 1892 by James Wilson, a farmer in Banffshire, northeast Scotland, and supports investigations into life in rural Scotland alongside food production past and present.

The impact of industrialization and urbanization provides the historical context for the programs, with the exception of Ruled by the Seasons, which exemplifies life in rural Scotland. For example, Victorian Glasgow displayed the best and worst features of a transforming economy with its population increasing from 275,000 to 762,000 between 1841 and 1901. Growing prosperity led to expanding suburbs with paved streets and private gardens contrasted with slum areas, where relatively large numbers of children died before their fifth birthday (Dicks, 1985; Gordon, 1983; Hillis, 2001). As a result, the Victorian period produced a wide range of primary sources, such as film, photographs, censuses, firsthand accounts, music, newspapers, and letters, that provide the raw materials through which students can investigate the past. Consequently, the Victorian period provides considerable potential for multimedia to justify its nomenclature.

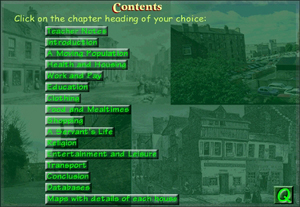

Figure 1. Table of contents, Auld Reekie and the Dear Green Place.

Figure 1. Table of contents, Auld Reekie and the Dear Green Place.

The Scottish multimedia resources contain primary and secondary sources alongside suggested activities and learning tasks. Auld Reekie and the Dear Green Place illustrates many of the features and sources common to each program. Figure 1 shows that the program contains chapters on many aspects of life in Victorian Edinburgh and Glasgow.

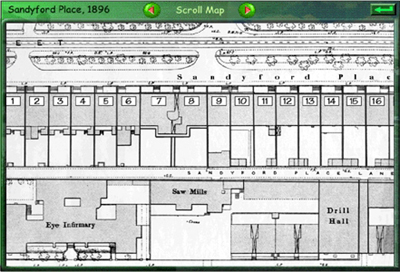

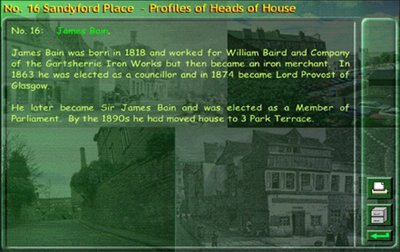

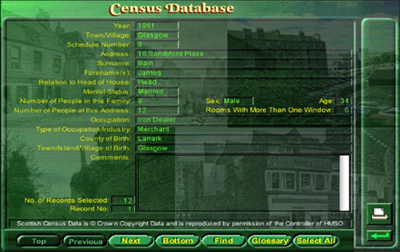

The program also allows students to analyze contrasting socioeconomic areas of each city. For example, Sandyford Place in Glasgow characterized the expansion of middle-class suburbs to the west of the city, whereas Malta Street contained slum housing. Clicking on the name of the street brings up the 1896 Ordnance Survey Map linked to other primary sources, including a photograph of the property, information on the residents where traceable, and census returns for 1851 and 1891. Figures 2, 3, 4, and 5 for 16 Sandyford Place illustrate some of these sources.

Figure 2. 1896 Ordnance Survey Map for Sandyford Place.

Figure 2. 1896 Ordnance Survey Map for Sandyford Place.

Figure 3. Profile of James Bain. Figure 4. Photograph of James Bain.

Figure 3. Profile of James Bain. Figure 4. Photograph of James Bain.

Figure 5. 1851 Census Return for 16 Sandyford Place. Entry for James Bain.

Figure 5. 1851 Census Return for 16 Sandyford Place. Entry for James Bain.

Census databases form the backbone to the programs since they give a unique insight into many aspects of society, including families, occupations, ages, places of birth, servants, and lodgers. As will be discussed later in this article, census databases support the central process in history, that of framing questions, finding answers, and subsequently reporting the results. Student tasks, differentiated when required, include extended writing, devising and giving presentations, sorting and matching, role play, compiling databases, taking notes and quizzes, conducting surveys, engaging in creative activities, and taking a critical skills challenge. This diverse range of learning tasks and sources aims to match many of the diverse student learning styles in the history classroom (Gardner, 1999).

The census databases illustrate how the programs are more than repositories of information. Students could study copies of the original census using microfilm in a library, but the databases in the programs contain thousands of entries covering many separate reels of film and no longer obtainable as paper copies. Moreover, a manual search of this many returns is not time-feasible in a school setting, whereas a database carries out sophisticated searches in a matter of seconds. In addition to providing primary sources in a manageable format, the CD ROMs link these sources in ways that support students in building a picture of the past.

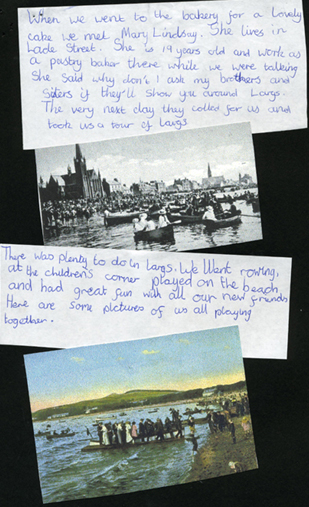

The firsthand accounts of the farming year link to film and photographs and are linked, in turn, to the census database and the returns for the farms being worked. The CD ROMs also contain resources such as archive film and photographs to show trainee teachers the further potential of ICT. Using programs such as Apple’s iMovie and Microsoft’s Moviemaker, students can create their own films of work on the land from archived film held in the CD ROM. New technology also supports alternative ways of presenting traditional sources. The traditional holiday scrapbook in Doon the Watter takes a new format with digital photographs and film, but as Figure 6 shows, there is still a place for an older format.

Figure 6. One page from holiday scrapbook of “going doon the watter.” Students traced Mary Lindsay in the census database.

Figure 6. One page from holiday scrapbook of “going doon the watter.” Students traced Mary Lindsay in the census database.

Therefore, the programs aim to help students analyze and interpret a variety of traditional historical sources within a multimedia environment. The sources are supported by learning tasks to develop knowledge, understanding, and skills. The primary sources and learning tasks were a major focus in student evaluation of the CD ROMs.

Evaluation

The evaluation of the various CD ROM teaching resources took place at several levels: questionnaires completed by students and teachers, ongoing informal interviews, cooperative teaching between the author and classroom teachers using each CD ROM, with production of DVDs showing teachers and students working with the programs to illustrate the integration of ICT into teaching and learning. In all, 275 students between 10 and 17 years and 11 teachers in 11 schools evaluated Auld Reekie, Doon the Watter, Barnhill, Ruled by the Seasons, and Changing Scotland. Schools were selected because they taught the relevant topic, such as the Victorians. One school that evaluated Ruled by the Seasons was chosen because James Wilson, the farmer featured in that volume, had attended there as a student. The evaluation took place between 1993 and 2009 in line with the production date of each CD ROM, with a key aim being to enhance the value and applicability of each program.

I wrote the evaluation questionnaire, but students and teachers independently answered the questions. Questionnaires asked for student evaluation of the primary sources and the learning tasks, with further questions focussing on general reactions to the programs and the impact on ICT skills, knowledge, and understanding. The questionnaire also asked students to record five key findings, which they had learned with a separate section that focused on the critical skills challenge. It was completed at the end of the topic and contained both open-ended and forced-choice responses. For example, students were asked to tick a box beside the primary sources that had been studied, but then answered an open-ended question on which had been the most useful, with an explanation for this choice.

The programs are non-profit-making. This fact does not in itself negate the wish for positive comments, but criticisms were encouraged, and many suggestions were incorporated into subsequent programs. For example, in early evaluations teachers recommended that some students were helped by being able to listen to sound recordings of written sources; therefore, an actor recorded all the extracts from Wilson’s journal featured in the final CD ROM, Ruled by the Seasons. More difficult words were always hyperlinked to definitions and, in some cases, to an online dictionary. The evaluation process also tested each program’s reliability and robustness on a wide variety of computers and operating systems.

Ongoing interviews were used to flesh out student reaction to the program and the associated learning tasks. Many extracts from these interviews were used as a sound track to the DVD. For example, students using Ruled by the Seasons were asked to explain key features of the banner they were making depicting life in rural Scotland. The explanation runs alongside film of the same students designing and making the banner.

I taught cooperatively with the teachers in three of the 11 schools, beginning with an initial demonstration of the program. This initial demonstration was short, a maximum of 90 minutes at the end of the school day, focussing on the program itself, especially the census database. The length of time given over to cooperative teaching varied between the programs, and in no case did it extend beyond eight afternoons per CD ROM, representing less than a quarter of the time given over to the topic. I helped students work through either the relevant activities in the CD ROM or others designed by the teacher.

Teachers evaluated key features of each program, including student reaction; ease of use; content and sources; and the impact on teaching, learning, classroom management and organization, knowledge, understanding, and skills. Teachers also evaluated the critical skills challenges and were encouraged to recommend improvements.

The evaluation did not assess the impact on achievement, partly because there was no comprehensive assessment of the topics, and it was not practicable to establish control groups that could have received traditional instruction. One evaluation of Ruled by the Seasons was carried out by students in a composite primary 5, 6 and 7 class in a small rural primary school. Therefore, many of the findings are qualitative. The qualitative observations were collated under headings such as “help visualizing the past” for relevant comments on the film and photographs. A frequency table recorded the number of students noting improvements in key skills.

Findings

One feature of the findings from the evaluations is consistency across each program, with key findings relating to the adaptability of the programs to different classroom settings and curricular goals, the primary sources students rated as the most useful, the wide range of cross-curricular work supported by the programs, the development of knowledge and skills in and beyond the history classroom, and the impact of authentic learning. This study draws on evidence from several programs rather than just one, thus providing a wider perspective concentrating on four key areas: student evaluation of the primary sources, the impact on cross-curricular activities, skill development, and observations on the authentic challenges. Students valued most highly the census databases, film, and photographs, which they considered helped them develop skills such as using a computer and searching a database. Each program developed a wide range of knowledge and skills across the curriculum, including social and presentation skills in the authentic challenges.

In the Classroom

History courses in Scotland cover significant elements of the nation’s history, including themes such as emigration, immigration, and housing, alongside the evaluation of historical evidence. These are featured in Auld Reekie to help teachers and students satisfy many national course requirements in terms of content and skills.

Teachers have used the programs and sources in varied and flexible ways. One school used Auld Reekie to focus on Victorian housing, whereas another school used the census database to illustrate patterns of migration. Doon the Watter provided a local history topic for one school in a town that had been a popular holiday destination, while another school used it as a key resource for a class topic on rivers. The guides to note taking and essay writing were the main focus for one class working on Changing Scottish Society. Another class used this program’s census database, especially people recorded as born in Ireland, when studying emigration and immigration. This flexible usage highlights one advantage in providing a range of sources and activities, a menu from which teachers can choose.

The availability of computers and electronic whiteboards were important influences on the way teachers managed the programs. A computer laboratory or class sets of laptops allowed students to work individually or in pairs, but classrooms with only two or three computers necessitated a different approach, with students working either individually, in pairs, or in groups on a range of computer and non-computer-based tasks. The latter were often printed from the program. Electronic whiteboards facilitated whole-class teaching based on the sources within the CD ROM. The following description from a teacher illustrates how the programs linked sources and learning tasks:

At first [we utilized] whole class explanation and use of CD ROM using smart boards. Subsequently, one or two students [used] each PC working through tasks for each aspect of the topic. They printed out answers/notes from the note-taking facility for me to look through before returning them for future revision. At the end [of the task, the students] used the Smartboard again to explain/discuss essay writing. Each student also had their own copy.

Census data provides a wide range of information, which is partly reflected in the different ways it was utilized in each program. Students are taken through Barnhill by a boy of approximately their own age who features in a photograph of street children. He introduces the topic by asking students to search the Barnhill census database for inmates of their own age. This begins to build an empathy with people in the past, with the fact that one girl had been born in Canada generating discussion on possible reasons for her being in the Poorhouse opening into wider questions around patterns of migration and poverty.

The chapter on “A Servant’s Life” in Auld Reekie begins with database searches for servants in two socioeconomically contrasting areas of Glasgow and Edinburgh, leading into initial questions on what these results say about each area. However, the program leads students into deeper questions about servants: What were their jobs? Where were they born? What were their ages? Why did they move to Glasgow/Edinburgh? How much did they earn? These and other similar questions open up major themes, such as migration from the countryside to towns. Follow-up activities include designing a section of a wall frieze depicting the daily routine for a servant compared to the routine for a student today.

Doon the Watter begins with a photograph taken at the beginning of the Glasgow Fair holiday in 1890, showing crowds of people in Glasgow Central Railway Station. A discussion based on the framework follows with four key questions: What does the photograph tell us? What can we infer? What does it not show? And what else would I like to find out? Additional questions include the following: Why were so many people in the station? What evidence is there that there were people of different ages? What is noticeable about their clothes? (Everyone was wearing a hat because people bought two hats during the year, one for New Year and one for summer holidays.) How are they going to travel? Where might they be going and what else would I like to find out? The last question leads students into the topic.

In Changing Scotland, the section on “The Growth of Towns and Cities” opens with a photograph taken in 1875 of people standing outside McConnachie’s Close in Edinburgh. A close is the entrance to a series of flats within a tenement. In the next stage of this investigation, students search the 1881 census database to find everyone recorded as living in the tenement. This data, in turn, provides a scaffold for questions regarding places of birth, reasons for moving to Edinburgh, occupations, and overcrowding. Students then access sources including film and firsthand accounts on the reasons for increasing urbanization and living conditions. In this way, the CD ROM integrates diverse but related primary and secondary sources.

Although the programs suggest some database searches, students are encouraged to devise their own questions, which in turn, lead to interrogation of the information. For example, a student studying the impact of living conditions compared age profiles between middle and working-class localities. One student summed up this process by noting, “We first looked at the census which was interesting. Then we went deeper looking at people’s lives and where they had lived. We also found out about where they would go on holiday.” This practical example is consistent with Schick’s (2000) teaching equation lying at the heart of effective computer programs, which should not just take students through a program, but be more demanding in asking questions that make students think differently.

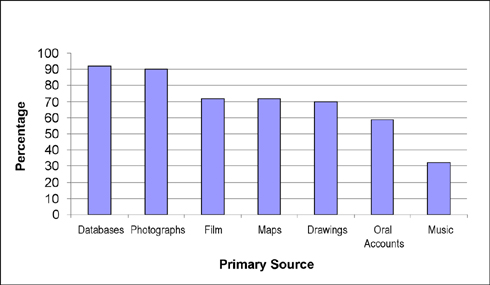

Primary Sources

Figure 7 represents the percentage of students who studied the seven most common sources in Auld Reekie with similar results for the other programs. Students rated the census database, film, and photographs as the most helpful sources in studying the past. One student noted that the database was helpful “because we learned about where people were from, age they died, occupation and if they were married.” Film and photographs were useful. “They gave an insight into the way people lived and showed the information in a visual form rather than just reading,” recorded one student. Teachers corroborated these comments, noting that learning was supported by “using the database,” “comparing then and now pictures,” and “watching films.”

Figure 7. Primary sources studied by students.

Figure 7. Primary sources studied by students.

Cross-Curricular Themes

Figure 8. Banner depicting Ruled by the Seasons.

Figure 8. Banner depicting Ruled by the Seasons.

In Audio 1, teachers and students reflect on how Ruled by the Seasons supports crosscurricular activities, including art and design, and develop thinking skills. Figure 8 shows the banner as described by the teacher and her students.

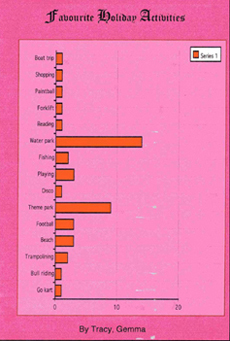

Consequently, crosscurricular themes included art and design, field trips, numeracy, sowing and planting, and technology. Figure 9 provides an example of numeracy through devising, carrying out, and displaying the findings of a questionnaire on holiday activities and destinations.

Skills In and Beyond History

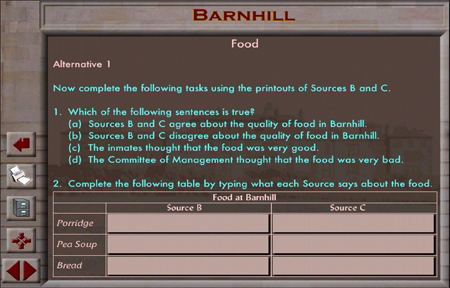

The contentious nature of many themes within each program gave rise to sources with conflicting evidence and allowed students to develop skills of weighing opinions and discriminating. A protracted and public argument over the quality of food in Barnhill was one notable example. This debate began in December 1852 with a letter in The Glasgow Sentinel “signed by 57 of the residents” complaining about the food and conditions in Barnhill. The porridge was “skilly or water gruel,” bread had “the composition of sawdust,” “peas-meal water” more accurately described the pea soup, the wards were cold and damp with children “standing shivering upon stairs and passages till they are driven to school into a ground-floor room…”

Figure 9a. Results of questionnaire on holiday activities. Figure 9b. Results of questionnaire on holiday destinations.

Figure 9a. Results of questionnaire on holiday activities. Figure 9b. Results of questionnaire on holiday destinations.

An investigation by the Poorhouse’s Committee of Management concluded that “although the porridge was thinner … a greater quantity was allowed,” the pea soup was “very good in quality and better than many working men received in their own home,” and “the same report on pea soup applies to bread.” These sources support differentiated tasks on the nature and possible reasons for the contrasting evidence. Figure 10 is one card from this sequence of activities.

Figure 10. Contrasting evidence from Barnhill.

Figure 10. Contrasting evidence from Barnhill.

From this task and the follow up, students were able to suggest reasons for the conflicting evidence:

Because Source C did not want to pay more money and in Source B the inmates said the food was horrible because they ate it. Because the people who ran the poor house wouldn’t have wanted to spend more money or be in trouble.

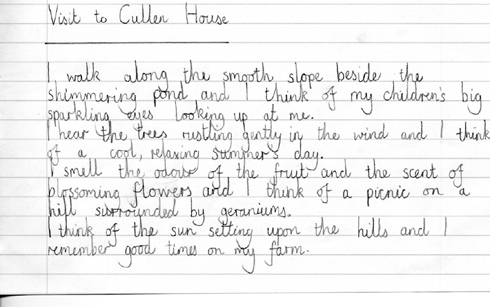

The programs also aim to support more extended writing in various formats partly in response to national concerns over standards of literacy (Scottish Executive, 2008). Four examples of these varied formats are poetry, letter writing, short essays, and note-taking. One extract in Ruled by the Seasons gives a detailed account by James Wilson of a visit to the extensive gardens of Cullen House, home of the local landowner. Students use this description to compose their own poem based on the visit to Cullen House (see example in Figure 11). Audio 2 gives one student’s evaluation of the farmer’s writing.

Figure 11. Poem based on a visit to Cullen House.

Figure 11. Poem based on a visit to Cullen House.

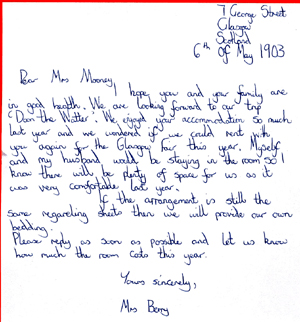

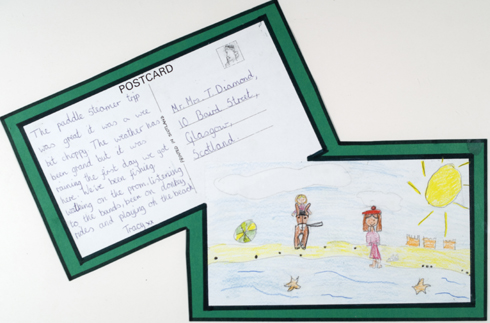

When using Doon the Watter, students wrote a letter to book their holiday accommodation (Figure 12). Students also made holiday postcards (Figure 13).

Figure 12. Letter to book holiday accommodation.

Figure 12. Letter to book holiday accommodation.

The section on “Causes of Poverty in Barnhill” concludes with a task requiring students to write a short essay giving reasons for increased levels of poverty. There are a variety of supporting templates for extended writing, with Causes of Poverty providing a passage with several possible reasons from which students select relevant sections, place these in a logical sequence, and write the resulting short essay (Scott, 2006). Using this support, one student wrote,

In the nineteenth century Glasgow grew into a large city. Thousands of people came to live and work in the city, but there were not enough houses. People’s houses were very small and there was no clean water or proper sewage system. This meant that disease spread quickly through the slums.

People worked in new industries such as cotton, iron and shipbuilding. The chemical industry in Glasgow was the largest in the world.

Many people did not have enough money to live on. They were paid very low wages and when they were ill they were not paid at all. Whole families had to work. Children and their parents worked in the cotton factories to earn as much money as possible. Working conditions in many of the new factories were difficult and dangerous. Low wages meant that people did not have much money to spend on food. Many families could not afford to eat well and lived on bread, milk, potatoes and oatmeal. This also affected their health, but when people were ill they could not afford to go to a doctor. For a large number of people life in Victorian Glasgow was very hard.

Figure 13. Holiday postcard.

Figure 13. Holiday postcard.

A similar exercise in Changing Scotland provides less support in terms of content, but emphasizes essay structure through the original hamburger analogy of an essay having three components: introduction, development, and conclusion (Barnham, 1998). Changing Scotland encourages note-taking by providing general guidance and specific pointers.

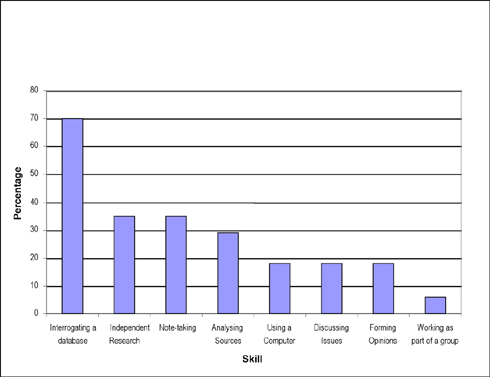

In the chapter on the growth of towns and cities, these pointers direct students to take notes on (a) the major trends in Scottish population and continuing development of urban areas, followed by (b) housing and living conditions. Subheadings for the major trends cover what happened to Scotland’s population between 1881 and 1939 alongside the growth of urban areas and comparison with other countries. These subheadings link to the relevant cards containing information in formats ranging from firsthand accounts, film, and photographs to the census database. Figure 14 shows the number of students (n = 25) who reported an improvement in a range of skills, such as independent research and note taking, when studying Changing Scotland.

Figure 14. Number of students rating skill development in the top two categories for Changing Scottish Society.

Figure 14. Number of students rating skill development in the top two categories for Changing Scottish Society.

These examples of extended writing combine traditional activities with new technology, but the CD ROMs also bring video production into the classroom. Given that multimedia “permeates nearly every aspect” of our social and cultural worlds, it is important for students to experience its production (Debiase, 2008, p. 2839). Ruled by the Seasons holds a separate file with clips of archive film illustrating each stage of the farming year from ploughing to harvesting. Students can use programs such as iMovie to sort, edit, and compile visual material and add captions, sound, and transitions to create their own documentaries. Students supplement the media contained in the CD ROMs via hyperlinks to sites containing archive film and photographs, such as the Scottish Cultural Resources Archive Network (SCRAN; http://www.scran.ac.uk).

In Ruled by the Seasons, students navigated from the CD ROM to SCRAN when searching for images of farming in their local area. These images were saved into a folder on the student’s computer for copying into the chosen format, such as Word or PowerPoint.

Authentic Learning

Many different areas of learning are brought together in the concluding section of Barnhill which presents students with an authentic learning/critical skills challenge based on a scenario set in 2080. Demolition of houses built on the site of the Poorhouse revealed artifacts from Barnhill, and archaeologists, the students, have been called in to investigate. A new museum of social work will display a selection of these artifacts and each archaeological team has been asked to prepare a presentation designed to persuade a panel of experts from the museum to display any three artifacts. The challenge incorporates assessment, since students draw up an evaluation sheet for the panel of experts to use when judging each presentation. This activity helps students think critically on the features of an effective presentation.

Students work on varied tasks ranging from choosing which artifacts to display to presenting their recommendations. The nurse’s uniform, the school desk, and the suitcase were the most popular choices in one school. One student recorded that she and her partner chose those artifacts “because we thought (they) had a lot of history behind them and they gave a good example of life in Barnhill.”

Students, working in pairs, prepared and gave PowerPoint presentations to other members of the class, the teacher, and an invited guest. Preparation also included writing a script to ensure that the accompanying oral explanation expanded rather than repeated information given on each slide. Other tasks ranged from selecting artifacts, planning via a storyboard, typing information onto each slide, selecting images, and choosing background/foreground colors and animations to deciding who would give each part of the presentation.

The following comments encapsulate the general consensus when students were asked to record the ways in which the challenge helped improve knowledge of life in a poorhouse:

“It made me really think about being boarded out and the school etc.”

“We had to find out more for our presentation and we found out different things.”

“It helped improve my knowledge because it challenged me and gave me answers to different learning.”

“It was fun so I wanted to learn more.”

“[It] helped me improve my skill of looking for information and making and giving a presentation.”

These comments highlight the importance of motivation, problem-solving, real-life challenges, and ICT to teaching and learning. Nonetheless, in a pretopic self-assessment of ICT skills, all but two students in one class (N = 28) recorded that they need to practice making up a multimedia presentation. This finding concurs with Livingstone (2008) who has demonstrated that while “digital natives” are often quick and confident in using ICT in the form of the Internet, their range is often “narrow with little exploration” (p. 104) and is generally weak on creating resources. At the end of the Barnhill challenge, every student felt more confident in preparing a multimedia presentation.

The integration of assessment into the Barnhill challenge was central to learning, with students developing criteria for an effective presentation. Students rated on a scale of 1 to 5 how five aspects of this task helped them devise and give a presentation, with the highest ratings given to “helped me know exactly what to do,” “helped me decide what to put in the presentation,” and “helped me know what the audience was looking for.” Therefore, assessment supported learning rather than being the tail which wagged the dog, so to speak.

Conclusion

Student evaluation of the Scottish multimedia resources supports Wiley and Ash’s (2005) conclusion that “one of the most powerful sources of information for historians are data archives, such as census data” (p. 383). These, alongside a range of other primary sources, helped students investigate the past through a process which began by asking questions and ended with presenting the conclusions. At a time when history’s place in the curriculum is increasingly challenged (Munro, 2003), it is important that student teachers are able to argue from specific examples that this “queen of disciplines” occupies a unique position in education and makes a significant contribution to cross-curricular knowledge, skills, and topics. However, the authentic challenges demonstrate that these and other similarly broadly based activities rely on the knowledge and skills developed by subjects.

The programs also importantly demonstrate to teacher trainees some of the ways in which ICT can enhance teaching and learning. This demonstration is grounded in what actually works in the classroom and, as such, has been widely used in courses within the faculty of education. These courses cover trainee primary and secondary teachers who have several opportunities to study and work with the programs. The CD ROMs feature as part of lectures and workshops that are also accessible online, including You Tube, to provide teachers with an introduction to Ruled by the Seasons (http://il.youtube.com/watch?v=2u-99reG7N0&feature=related)

The in-faculty lectures include displays of student work and a wall display produced by students and teachers for Ruled by the Seasons as shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16. Wall Display Produced from Ruled by the Seasons.

Figure 16. Wall Display Produced from Ruled by the Seasons.

Trainee teachers study a DVD showing students and teachers working with the programs and the associated activities. The programs can be examined in computer laboratories and freely downloaded onto the trainee teachers’ laptops. Finally, the issues surrounding the application of these and other examples of ICT form the basis of discussions in tutorials.

The CD ROMs feature themes from Scottish history, but they have parallels in many other countries. Industrialization, urbanization, rural transformation, contrasts between rich and poor, popular culture, and patterns of migration were repeated across the United Kingdom, North America, and beyond. The primary sources featured in the CD ROMs can be located in many other countries, as illustrated by examples from the USA. Blackwell Island Workhouse was New York’s Barnhill (Berdy & The Roosevelt Island Historical Society, 2007). A similar program could be produced for each institution using the same range of sources, including photographs, film, firsthand accounts, newspaper articles, and the like (New York Times, 1897).

These sources can be used in similar ways with, for example, the census providing an opening into the topic and an important vehicle for further inquiry. Furthermore, and of equal importance, the learning tasks within a program such as Barnhill have a much wider application in that the tasks remain constant while the contexts alter. The same authentic challenge concluding Barnhill applies to Blackwell Island while writing frames, poetry, note-taking, and art work all cross the Atlantic.

Cities in North America witnessed a widening gap between rich and poor. In a more rural context, the Texas Irrigation Canal provides just one example of the impact of Scottish emigration to North America. Scottish-born rancher Patrick W. Thomson devised a project to build an irrigation network that would draw water from the Rio Grande forming the Eagle Pass Irrigation Company. Work began in 1889 with the completion of 3 miles of canal before the project was stalled by lack of funds (Pingenot, 2008). The canal itself, alongside relevant primary sources, leads students into examining many issues raised by patterns of migration.

Prensky (2001) referred to the gap between “digital natives,” young people who have grown up with new technology, and “digital immigrants,” those who were not born into the new digital age but have taken on board many of its aspects while still retaining a foot in the past. This is a powerful argument for teachers to adapt their pedagogy, but they should not be deterred from developing their students’ skills in ICT, especially in the creative dimension. Being technologically savvy does not automatically equate to being fully ICT literate.

In some respects Prensky’s divide applies to the Scottish CD ROMs in that they combine aspects of new technology with the traditional. The traditional comes in the form of primary sources, but new technology makes these more accessible and supports a greater variety of learning tasks than hitherto. Nonetheless, the vital link between new technology and primary sources has been the learning tasks which trainee teachers can adapt for use in their classrooms.

References

Barnham, D. (1998). Getting ready for the Grand Prix: Learning how to build a substantial argument in year 7. Teaching History, 92, 6-14.

Berdy, J., & The Roosevelt Island Historical Society. (2007). Blackwell Island prison and workhouse. Retrieved from the New York Correction History Society website: http://www.correctionhistory.org/rooseveltisland/berdybook.htm

Calandra, B., & Lee, T. (2005). The digital history and pedagogy project: Creating a interpretative/pedagogical historical website. The Internet and Higher Education, 8(4), 323-333.

Calder, L. (2006). Uncoverage: Toward a signature pedagogy for the history survey. Journal of American History. Retrieved from http://www.indiana.edu/~jah/textbooks/2006/calder/shtml

Debiase, M. (2008). Video documentaries as content and tools to new learning experiences: Recreating history with shared resources. In J. Luca & E. Weippl (Eds.), Proceedings of the World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications 2008 (pp. 2839-2845). Chesapeake, VA: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education.

Dicks, B. (1985). Choice and restraint: Further perspectives on socio-economic segregation in nineteenth century Glasgow with particular reference to its West End. In G. Gordon (Ed.), Perspectives of the Scottish city (pp. 91-124). Aberdeen, Scotland: Aberdeen University Press.

Fairley, J. (1970). Patch history and creativity. London, England: Longman.

Gardner, H. (1999). Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the 21st century. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gordon, G. (1983). The status areas of Edinburgh in 1914. In G. Gordon & B. Dicks (Eds.), Scottish urban history (pp. 168-198), Aberdeen, Scotland: Aberdeen University Press.

Haydn, T. (1996). Thinking, computers and history. History Computer Review, 12(2), 13-23.

Herrington, J., Reeves. T., Oliver. R., & Woo, Y. (2004). Arranging authentic activities in Web based course. Journal of Computing Higher Education, 16(1), 3-29.

Hillis, P. (2001). Contrast and change in selected residential areas of Edinburgh and Glasgow, 1850-1900. The Local Historian, 31(3), 168-188.

Learning and Teaching Scotland. (2000). Environmental studies, 5-14 national guidelines. Dundee, Scotland: Scottish Schools Equipment Research Centre

Learning and Teaching Scotland. (2009). A curriculum for excellence. Social studies outcomes. Retrieved from http://www.ltscotland.org.uk/myexperiencesandoutcomes/socialstudies/index.asp

Learning and Teaching Scotland. (2010) Curriculum for excellence. Retrieved from http://www.ltscotland.org.uk/curriculumforexcellence/index.asp

Lee, P. (1991). Historical knowledge in the National Curriculum. In R. Aldrich (Ed.), History in the National Curriculum (pp. 34-65). London, England: Kogan Page.

Lee, K.L., & Clarke, G.W. (2004). Studying history in the digital age: The story of Asaph Perry. Social Education, 68(3), 203-207.

Livingstone, S. (2008). Internet literacy: Young people’s negotiation of new online opportunities. In T. McPherson (Ed.), Digital youth, innovation and the unexpected (pp. 101-122). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Munro, N. (2003). Radical new look for the curriculum, Times Educational Supplement, Scotland, 1, 26.

New York Times. (1897, November 13). Our charities: The institutions on Blackwell’s Island. Retrieved from http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. Retrieved from http://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf

Riley, C. (1999). Evidential understanding, period knowledge and the development of literacy. Teaching History, 97, 6-12.

Schick, J.B. (1995). On being interactive: Rethinking the learning equation. History Microcomputer Review, 11(1), 9-25.

Schick, J. (1996). Multimedia: What, where and why not? In J.P. Lehrers, A. Martin & F. Hendrickx (Eds.), Information technology for history education (pp. 235-251), Luxembourg, Germany: University of Luxembourg.

Schick, J. (2000). Building a better “mouse” trap. Schick’s Taxonomy of Interactivity. History Computer Review, 16(1), 15–28.

Scott, A. (2006). Essay writing for everyone. Teaching History, 123, 26-33.

Scottish Executive. (2008). Adult literacy and numeracy in Scotland. Retrieved from http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resources/Doc/158952/0043191.pdf

Scottish Qualifications Authority. (2009). Standard grade arrangements in history. Retrieved from http://www.sqa.org.uk/files_ccc/NQHistoryStdGArrangements.pdf

Scottish Qualifications Authority. (2009). National qualifications, Higher history. Dalkeith, Scotland: Author.

Seixas, P. (1993). The community of inquiry as a basis for knowledge and learning: The case of history. American Educational Research Journal, 30(2), 305-324.

Seixas, P. (1996). Conceptualizing the growth of historical understanding. In D. Olson & N. Torrance (Eds.), Education and human development (pp. 765-783). London, England: Blackwell.

Seixas, P. (1997). The place of the disciplines in social studies: History. In I. Wright & A. Sears (Eds.), Trends and issues in Canadian Social studies (pp. 116-129). Vancouver, BC: Pacific Educational Press.

Seixas, P. (1998). Student teachers thinking historically. Theory and Research in Social Education, 26(3), 310-341.

Shulman, L.S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1-22.

Swan, K.O., & Hofer, M. (2008). The Historical Scene Investigation project: Facilitating historical thinking with web-based primary source documents. Journal of the Association for History and Computing, 11(1). Retrieved from http://mcel.pacificu.edu/jahc/2008/issue1/swanhofer.php

Taylor, T., & Young, C. (2009). Making history: A guide for the teaching and learning of history in Australian Schools. Retrieved from the National Centre for History Education website: http://hyperhistory.org/

Wiley, J., & Ash, I. (2005). Multimedia and learning of history. In R. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (pp. 375-391). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Author Info

Peter Hillis

University of Strathclyde,

Glasgow, Scotland

email: [email protected]

![]()